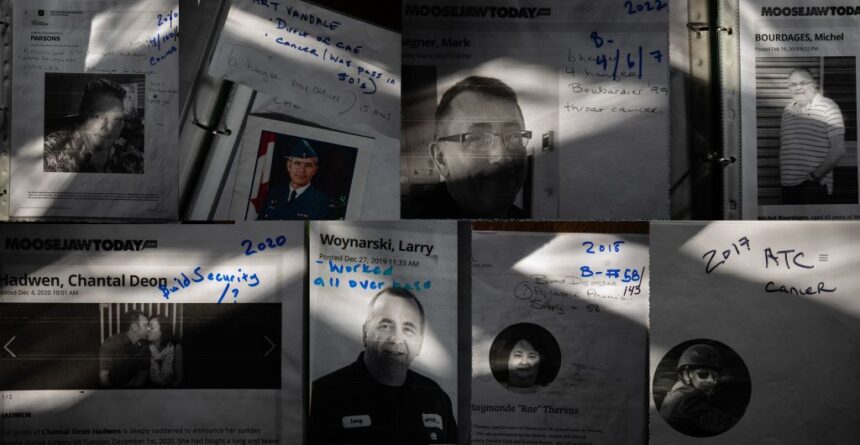

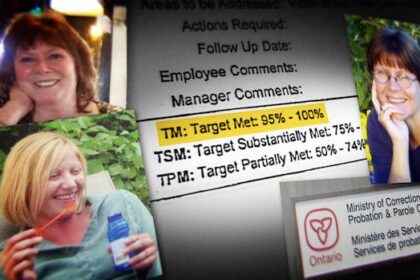

Erin Zimmerman, a 46-year-old mother, wife, artist, public servant and veteran, has called the small city of Moose Jaw, Sask., population 35,000, home for the last 25 years. She joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 2012 and since 2016 has been working as a financial clerk at the Moose Jaw military base, most recently in an office she now fears: Building 143. One morning in 2019, three years into her role, Zimmerman woke up with crossed eyes. At first she assumed she was having an odd migraine, but after seeing an eye doctor, it became clear the issue was brain-related, which Zimmerman said was terrifying. Since then, she’s seen neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists and other specialists. In early 2024, she was diagnosed with a rare form of early-onset Parkinson’s disease, a disorder of the brain and nervous system which worsens over time. Erin Zimmerman researches environmental contamination at the Canadian Armed Forces base in Moose Jaw, Sask. Zimmerman, a Snowbird veteran who also worked as a civil servant, has early onset Parkinson’s disease and has been pushing for answers about environmental contaminants, suspecting they are causing a rash of negative health impacts for people working and living on base. Zimmerman said her doctors explained her illness can be caused by a mix of genetic and environmental factors. They laid out the potential causes of a rare early-onset of the disease. One was severe head trauma, which Zimmerman never had. The other was exposure to toxic chemicals. For Zimmerman, the latter was “a red flag,” which led her to start investigating contamination and environmental hazards at her workplace. “I learned that while I was serving, and even during my pregnancy, I’ve been working on, or next to, a contamination site,” Zimmerman said about going through government documents and collecting testimonies of others who had served. “I also heard that others in our building were experiencing serious illnesses.” Zimmerman said her journey began as a personal health crisis but, since learning of her colleagues’ illnesses including autoimmune diseases, thyroid diseases, cancer and other undiagnosed health issues, has grown into a larger discussion about her workplace safety and her employer: the Department of National Defence. There are thousands of contaminated sites listed on the federal contaminated sites inventory, including military bases like CFB Moose Jaw, the home of the Snowbirds. Contamination on federal sites is an issue across Canada. There are thousands of contaminated sites listed on the federal contaminated sites inventory, including military bases with busy offices, hangars and warehouses on top of unremediated contamination sites. CFB Moose Jaw is one of them. She told The Narwhal her research has exposed gaps in how contamination sites are communicated to those working and living in contaminated areas. She’s compiled a list of nearly 200 illnesses and dozens of obituaries of her colleagues. While it’s difficult to pinpoint one cause for the variety of health issues Zimmerman and colleagues report, there are steps experts take to determine environmental causes for illnesses. “You’re talking about wide environmental exposures and … you look for clustering of specific diseases,” said Christine Oliver, a professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto who specializes in occupational and environmental health. “[On] one of these military bases, even if they’re office workers, you can look to see if people with similar symptoms or similar diagnoses are performing similar jobs.” Zimmerman has compiled a list of nearly 200 illnesses and dozens of obituaries among her colleagues. She worries they became ill after being exposed to environmental contamination on the base. The Narwhal obtained internal studies of contamination at Moose Jaw released to employees this year by Defence Construction Canada, a Crown corporation. When asked to review the studies, Sébastien Sauvé, a professor of environmental chemistry at Université de Montréal, pointed to reasons for concern. “Some of those concentrations are very high,” he explained. He said some of the dust samples’ PFAS (sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals”) values are higher than what he’s seen in contaminated soils right beside a PFAS chemical manufacturer, adding that “people working in some of those rooms would be exposed to PFAS from dusts.” In 2022, Suavé and a research team found these forever chemicals had spread from a contaminated military base in Bagotville, Que., to drinking water wells up to 10 kilometres away. “You sign on that dotted line, the expectation is you’re going to die for your country. Well, dying doesn’t mean I should get sick because of a chemical [the government] didn’t clean up properly.”– Lynn Point, former employee at CFB Moose Jaw Zimmerman is adamant something needs to be done on the base, including proactive disclosure by National Defence Canada about contaminants and their potential risks. “Not only was I unknowingly exposed, but many others may be at risk with no warning,” she said. “The diagnosis was life-changing, but it also feels like determination to find answers, not just for myself but others who may be affected.” Other employees of the base have begun publicly discussing illnesses they say are linked to the long-standing chemical contamination of the site. The Department of National Defence is aware of concerns about contamination on military bases and says it does testing and is committed to minimizing risks to Canadians. For its part, the military says its activities can have effects on soil and water, but “the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces are committed to the health and safety of personnel and surrounding communities,” as well as to “responsible environmental management.” Responding to questions from The Narwhal, a spokesperson wrote in an email the military “conducts regular monitoring programs at bases and wings to assess environmental conditions and identify potential concerns. Although routine testing had not indicated issues, following community concerns, we undertook extensive testing [in Moose Jaw] to ensure transparency and diligence in addressing concerns.” But for active and former service members like Zimmerman, that’s little assurance when it seems to them that so many of their colleagues are getting sick. PFAS exposure includes risks from infertility to cancer Moose Jaw’s slogan is “Canada’s Most Notorious City,” stemming from its historical connections with Al Capone. The Canadian Armed Forces base nearby, 15 Wing, is a smattering of buildings including housing, offices, a gym, hospital and convenience store, alongside hangars and an airstrip surrounded by a patchwork of quintessential Saskatchewan cropland and homes. It’s the workplace for about 1,000 active military service members and also federal public servants. It’s also the home of the Snowbirds, Canada’s military aerobatics flight demonstration team, for which Zimmerman was an administrative clerk before moving to her current job. CFB Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan is home to a Royal Canadian Air Force base. Areas on the base are contaminated with PFAS (also known as forever chemicals), asbestos and other contaminants. But 15 Wing is listed on the federal inventory of contaminated sites owned by the Canadian government. Sites on the base — aircraft hangars, former convenience stores and landfills — are polluted with several volatile organic compounds, petroleum hydrocarbons and PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in the groundwater and soil. Asbestos has also been found in some places on base, according to a 2025 report about testing conducted on the base last year. PFAS have been making headlines for the last several years for contaminating drinking water near military bases. They are found or suspected on more than 100 federal sites in Canada, in large part from firefighting foam that National Defence used to train military and civilian firefighters across Canada from the 1970s to the early 2010s. The United States Environmental Protection Agency lists numerous potential health risks of exposure to PFAS, including issues with fertility or in pregnancy, developmental effects in children, increased risk of prostate, kidney and testicular cancers and weakening of the body’s immune system, including reduced vaccine response. The Canadian government says PFAS can be transferred through the placenta during pregnancy and infants can be exposed through ingestion of human milk. Ecosystems are affected, too. Studies have shown exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances can cause reduced seed germination, stunted growth and reduced photosynthetic activity in plants. The chemicals can then build up in the organs of other creatures in the food chain. Contamination on the base stems from military use of solvents, fuels and firefighting foam. Other chemicals on the long list of contaminants near the 15 Wing buildings are less widely known. There are BTEXs, a group of petroleum hydrocarbons consisting of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene that can be found contaminating several sites on CFB Moose Jaw. They are used on military bases for many things, including as components of fuels; they can also be present from spills or leaks. They also have a long list of health impacts associated with inhaling them, accidentally ingesting them or making skin contact — including higher risks of respiratory and lung cancers, heart problems and heart failure, blood disorders and cancers, immune dysfunction and increased susceptibility to infections, according to a peer-reviewed study from the Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances. Another study from researchers at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences shows this group of BTEXs can play a role in neurological symptoms like Zimmerman’s headaches, nausea, and vision problems. Another contaminant found at CFB Moose Jaw is a class of chemicals — present in coal, crude oil and gasoline — called PAHs, or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. The Environmental Protection Agency says people can be exposed to mixtures of PAHs by breathing air contaminated with vehicle exhaust, or fumes from asphalt roads. The agency says that several individual PAHs and some specific mixtures of PAHs are considered to be cancer-causing. A bird takes flight from a chain-link fence around 15 Wing Moose Jaw. The military has been engaging in activities that create contamination for decades, including the firefighting training with PFAS-containing foam. But it’s far from the only organization or industry that’s been contaminating land in Canada — it’s just the one with public records. Some experts say the main reason we know so much about the contaminants present on military sites is because the federal government keeps pretty good records about what land is being used for. “A lot of this kind of disclosure and transparency relies on institutional memory. With the federal government, the documentation on those sites is probably much better than in other jurisdictions,” Cassie Barker, senior program manager for toxics at the advocacy organization Environmental Defence, said in an interview. “It’s not just on [military] lands that this occurs.” A Department of National Defence spokesperson responded to The Narwhal’s questions about contamination in an email. “We are aware that some employees working at 15 Wing Moose Jaw have expressed apprehensions about the health and safety of working within a building at Canadian Forces Base Moose Jaw.” The Lieutenant Colonel David V. Currie Armoury is located on Main Street in Moose Jaw, Sask. Dealing with environmental contamination on the CFB Moose Jaw base is the responsibility of the federal government and the municipality and the province have little involvement. The email said the department “has no concerns about the safety of this particular building at this particular time” but has still started a “transparent and evidence-based analysis” including air quality monitoring and an ongoing survey of Building 143. “Based on the contractor reports and feedback from multiple experts, there is no evidence to suggest that 15 Wing buildings are unsafe or unfit for occupancy,” the spokesperson added. Five women who worked together at CFB Moose Jaw have had hysterectomies: testimony In December 2024, Zimmerman and two other employees of the Moose Jaw base went to Ottawa to speak about their experiences — including cancers, infertility, neurological disorders and untimely deaths of colleagues — at a public hearing of the Standing Committee on National Defence. Current personnel and veterans from other bases also testified at the four meetings. Former NDP Member of Parliament and critic for National Defence Lindsay Mathyssen initiated the hearing after the issue of contamination in her Ontario riding came to her attention. (Mathyssen lost her seat in the April election and the fate of the study is uncertain.) “Thirty-one years ago, I was a young, married woman full of excitement and hope for my future. My husband was an aircraft engine technician,” Shaunna Plourde, Zimmerman’s colleague, told the committee. Plourde explained she was expecting her first baby when the family moved into quarters on the base. She started working as a clerk at the base convenience store, CANEX. People paint a fence around housing at 15 Wing Moose Jaw. Service members and their families who have lived on the base struggle with various health issues, from cancer to neurological disorders. “I felt incredibly proud of the life we were building, one centred on service, community and the Canadian dream,” Plourde testified. “I never imagined this dream would turn into a nightmare from which I cannot wake.” Plourde told the committee she soon began experiencing medical issues and, after seven years on base, was diagnosed with a neurological disorder. She said her children also struggle with health conditions including chronic lung issues. “I have lived and worked in buildings, sent my children to daycares and schools and used facilities that I now know are directly on contamination sites or within areas where contamination sites exist. Despite this, we were never told. … No one told us about the risks we were exposed to daily,” Plourde testified. Plourde’s own condition has progressively worsened. In 2017, she had an emergency hysterectomy. “Since this time, four other women I work with have all needed to have this procedure. Many of us were employed in the same building — Building 143,” Plourde said. “A simple, yet alarming, question started being discussed in the building I work in: ‘Do you think our building is safe?’ ” As they began piecing together the puzzle, she said, the employees realized there had been dozens of deaths in short succession of people that had worked in seven buildings listed on the federal public inventory of contaminated sites. Active and former military members have started to question whether they have been adequately protected from contamination, after dedicating their lives to service. Gord King worked at 15 Wing Moose Jaw Canadian Armed Forces base for 22 years and wonders if environmental contamination could have contributed to his stage two prostate cancer. The chief warrant officer, in charge of morale, welfare and quality of life of personnel at 15 Wing’s Canadian Armed Forces Flying Training School, acknowledged their concerns in an email to employees: “We acknowledge that concerns regarding Building 143 have been ongoing for some time, and we understand that this is a sensitive topic that evokes mixed emotions and concerns for many. The [Wing Commander] is fully aware of this, and is committed to addressing these matters with care and attention.” The Union of National Defence Employees told The Narwhal in an email that it is the “employer’s responsibility to provide a safe workplace,” saying that “Building 143 is not listed as a contaminated site. Further, the employer confirmed that there is no record of unsafe levels of PFAS in the building.” Meanwhile employees working in the building have struggled to get recognition from their leadership. “Those of us who have sought answers have faced skepticism, criticism and, now, retribution, but we persist, for those we have lost, for those who are suffering and for those who may yet be affected,” Plourde told the committee, pointing to what she sees as attempts at silencing concerns and consequences for those speaking out anyway, including social alienation. Had she known about the contamination, Plourde told The Narwhal, “I most likely never would have lived out there. I never would have worked out there. I probably would have stayed away from it as far as I possibly could.” Some employees say they would never have taken the job at CFB Moose Jaw had they been better informed about contamination issues on the base. Since the three colleagues took to Ottawa, dozens of others have spoken about their own experiences, though some say they are fearful of retribution at work and in their community. A spokesperson from National Defence told The Narwhal the “management of contaminated sites generally does not involve communication with employees or the local community until qualified environmental experts identify potential exposure risks.” But for employees worried about their health, the lack of communication is only the start of their concerns. ‘There’s still people sitting in chairs with toxic waste under their seat and they don’t know about it’ For 12 years, Lynn Point worked on the Moose Jaw base in Building 143, organizing logistics for uniforms and other gear. Now, she is undergoing treatment, including chemotherapy, for a rare form of breast cancer on her chest wall that has spread into her lymph nodes. Point told The Narwhal that two of her colleagues and her former supervisor have all died of breast cancer. “They worked hard … and they didn’t get to retire.” Point’s husband still works at 15 Wing, which concerns her: “I’m not happy with the fact that he’s still out there. I’d like him to relocate, but it’s not that simple. We need our jobs.” “I love the job, love the people, but our government failed us,” Point told The Narwhal. “To wear a uniform doesn’t mean that they should be able to abuse you that way. Because you sign on that dotted line, the expectation is you’re going to die for your country. Well, dying doesn’t mean I should get sick because of a chemical that you didn’t clean up properly.” Lynn Point, a 20-year veteran and a 12-year civilian employee of CFB Moose Jaw, believes her cancer is related to environmental contamination at the base. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2025, with a rare form that manifests on the chest wall rather than in breast tissue. She joined a meeting — current and former civil employees as well as veterans from the base — about the contamination at 15 Wing. Another former employee who got cancer worked for a contractor on CFB Moose Jaw in a three-person department. “It changes your life,” he told The Narwhal about his cancer diagnosis and current recovery including surgery, 33 trips to Regina for radiation and two years of hormone therapy treatment. The employee, whose identity The Narwhal agreed to keep confidential, said he and both of his colleagues all got prostate cancer within six months of one another. “There’s still people sitting in chairs with toxic waste under their seat and they don’t know about it,” said the employee, who served nearly 28 years in active duty, and 14 more in an office position on the Moose Jaw Base. “I just would like to make sure that they’ve done something so nobody else gets sick.” Since three CFB Moose Jaw colleagues took to Ottawa to share their stories about illness, dozens of others have spoken about their own experiences, though some say they are fearful of retribution at work and in their community. This employee said he was never compensated for his illness, despite his formal requests: “Workplace compensation needed to hear from [my] employer, so they contacted the base. They never got a response from the base,” he said. “So my file was terminated.” The Department of National Defence did not answer The Narwhal’s specific questions about workplace compensation at CFB Moose Jaw. Neighbours to Canadian Armed Forces contamination worry whether it seeped into drinking water Cities and even provinces do not have much jurisdiction over what occurs on bases. Typically, though air, water and soil contamination falls under the jurisdiction of a province, military sites are different. It is the responsibility of the federal Department of National Defence to monitor and clean up contamination on its sites. In Moose Jaw, the base is only about 15 kilometres from the city and is one of its major employers, with 15 Wing’s military aviation listed as one of the city’s “target industries,” on its website. When The Narwhal contacted the City of Moose Jaw and Mayor James Murdock, the city responded that since questions about contamination on the base and employees falling ill “pertains to an area outside the boundaries of the City of Moose Jaw,” it was unable to provide a comment. The mayor’s office also declined to respond to The Narwhal’s questions regarding the concerns of citizens living near the base. Moose Jaw is a community of 35,000 people in southern Saskatchewan. The military base is one of the major employers in the region. “What is in the workplaces tends to get out,” Oliver, the doctor who specializes in occupational and environmental health, said. “It is workers that are primarily concerned but it won’t be very long, I think, before people who don’t work there are concerned about their exposures.” Health Canada says some of these contaminants that are dangerous to public health can travel long distances through soil, water and air: “PFAS can be found in freshwater and drinking water in areas that are far away from where they entered the environment,” the department says on its website. It’s impossible to quantify if or how much contamination has seeped off the base without publicly available studies, but some nearby farmers and residents are beginning to ask questions about what they might be exposed to, like Chey Craik, who lives just over three kilometres away. A farmer’s field butts up against CFB Moose Jaw. “I wouldn’t think a chain link fence would stop contaminants from moving around,” said Chey Craik, who lives on a farm just over three kilometres away and whose family deals with health issues. “I have obvious neurological problems. My parents both live here on the farm too [in] the house I grew up in,” Craik said. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Both his parents suffer neurological issues as well and have struggled to find diagnosis or cause for their symptoms. Craik learned about contamination issues on base from employees. “It just puts more questions into our minds, like, ‘Is that a potential factor?’… I wouldn’t think a chain link fence would stop contaminants from moving around.” When asked by The Narwhal about the scope of the problem at the base and the health issues and concerns of citizens nearby, the Saskatchewan Health Authority said any contamination at CFB Moose Jaw is the responsibility of National Defence to identify and address. The provincial Ministry of Environment declined to comment. Raising awareness of contamination as a life’s mission Back at Zimmerman’s family home, she has dedicated her life to helping veterans and other military civil servants who say they have been impacted by contamination on base. She paints portraits of veterans dying of terminal illnesses and collects their testimonies. She has been helping colleagues around the country file claims to get justice, accountability and hopefully, compensation for their illnesses. She has gained a reputation in Moose Jaw for refusing to drop this contamination issue. “When I joined [the military], I took an oath that I would risk my life for what Canada stood for,” she told The Narwhal. “I’m not going to stop until I make a change.” Erin Zimmerman at home with an in-progress painting of her friend and mentor, Della Bennett. The women worked together at the Moose Jaw Canadian Armed Forces base, but Bennett died of cancer in 2021. Zimmerman has dedicated the rest of her years to raising awareness and pushing for solutions related to contamination on the military base she worked at. She stressed that she does the work because she loves her neighbours: “Moose Jaw is an incredible community,” Zimmerman said. “The sense of connection and support is strong. It’s a place where people take care of each other, and that’s what makes it super special.” Earlier this year, Zimmerman went on disability leave from her job without specific compensation for her Parkinson’s symptoms or official acknowledgment of the harms she’s suffered. Meanwhile, she said, she is acutely aware of her doctor’s prognosis that she may only have a decade left to spread the word about this issue. Recent Posts Is contamination on a Canadian Armed Forces base making employees sick? July 8, 2025 18 min. read ‘I took an oath that I would risk my life for what Canada stood for’:… Oil giant broke deal to deactivate thousands of pipelines and faced no penalty, documents reveal Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. failed to deliver on a promise to deactivate thousands of inactive… The weather edit: 2 big ideas for the climate These companies say their tech could help engineer our way out of climate change. Will…

Is contamination on a Canadian Armed Forces base making employees sick?