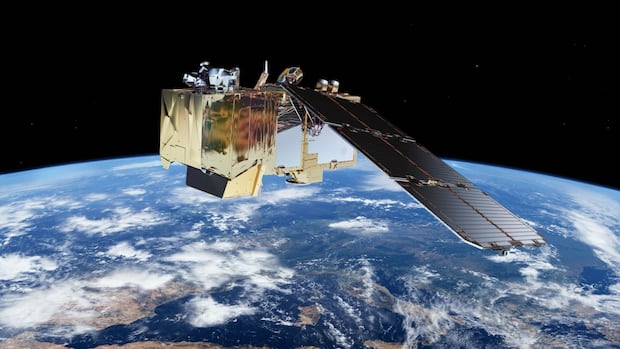

ManitobaThere were multiple overlapping signs on the Prairies detectable from space that provided an early hint of the devastating wildfire season Manitoba’s still fighting through, researchers say.Analysis suggests overlapping factors seen from space, including less lush vegetation, signaled season aheadBryce Hoye · CBC News · Posted: Aug 12, 2025 6:00 AM EDT | Last Updated: 5 hours agoIn an illustration, the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite is depicted orbiting Earth. Canada currently relies on its instruments to monitor and predict wildfires. A team out of University of Ottawa and Université Laval used Sentinel-2 and other tools to shed light on signs this spring that hinted at what’s become Manitoba’s worst wildfire season in three decades. (Submitted by ESA)There were multiple overlapping signs on the Prairies detectable from space that provided an early hint of the devastating wildfire season Manitoba’s still fighting through, researchers say.An analysis of satellite imagery by University of Ottawa and Université Laval researchers suggests moderately low rainfall in April, a moderately early spring snow melt, moderately dry soil, moderately parched vegetation and a moderate decline in overall “greenness” of vegetation had a compounding effect that helped transform Manitoba into a “highly flammable landscape.””All these drivers … create such a catastrophic event in, around the area,” said Hossein Bonakdari, associate professor in the department of civil engineering at the University of Ottawa.Bonakdari and his co-authors say their findings support more widespread use of satellite imagery for wildfire forecasting and emergency preparedness planning as wildfire seasons grow longer and more intense due to climate change.Their work was published this month in the journal Earth.The researchers combined historical drought data from the Canadian Drought Monitor with a review of satellite imagery from Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 satellites to look for precursors to wildfires.Canada has relied on the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 for several years to help monitor wildfires from space. In 2029, the Canadian Space Agency hopes to launch its own satellite, WildFireSat, so emergency officials could become less reliant on collaborators outside Canada.A map of the province of Manitoba shows four burn areas impacted by wildfires in May of 2025, including a fire in the Lac du Bonnet region and Nopiming Provincial Park in the east and southeast of the province. (Hossein Bonakdari)Bonakdari and his collaborators focused on identifying preconditions for wildfires in Manitoba this year — the worst wildfire season in three decades.Researchers found low soil moisture, an earlier warm-up in the spring with less precipitation and a big drop in snow coverage.Hint hidden in leavesThey also looked at foliage from above — leaf coverage both from needled coniferous and leafy deciduous trees — as well as how green vegetation was in the lead-up to the fire season.The idea is if the vegetation is browner, it’s holding less moisture. Less moist vegetation means more potential fuel for fire.An image of wildfires in the Nopiming region on May 31 taken from satellite Sentinel-2. (Submitted by Hossein Bonakdari)Their analysis found that this April, the month before fires kicked off, Manitoba’s forest canopies were less lush and less green than usual.That’s in contrast to a number of dry Aprils in the past couple decades — in 2008, 2018 and 2023 — that didn’t result in the scale or intensity of fires seen this season, the study states.They could also see where fires that rapidly spread in the north and east of the province started on May 4 and 14 amid pockets of warm and windy days.In hindsight, the stunted leaf development and green-up looks like an early sign that vegetation was under stress, maybe due to water scarcity and warmer temperatures earlier in the year, according to the study.That hypothesis is further bolstered when you consider the fact there was nearly eight millimetres less rainfall compared to the norm this April, and 40,000 square kilometres less snow pack in Manitoba in the winter lead-up to the fires.”Such early-season dryness leads to rapid fuel desiccation, particularly in fine fuels like grasses and small shrubs, which are critical to initial fire ignition and spread,” the authors state.”Reduced snow insulation, combined with dry and stressed vegetation, likely amplified the vulnerability of Manitoba’s landscape.”‘Slightly drier conditions start adding upSpatial anomalies of key environmental variables across Manitoba during April 2025: (a) leaf area index (LAI) derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) product MCD15A3H, (b) precipitation (mm) obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5-Land dataset, (c) air temperature (°C) obtained from ERA5-Land, and (d) January–May 2025 soil moisture anomaly (m3/m3) sourced from the ERA5-Land. The burned areas are shown as polygons with black outlines (Hossein Bonakdari et al 2025). (Hossein Bonakdari/University of Ottawa)The research suggests you don’t need a record heat wave, drought, low precipitation or low leaf coverage or greenness all together in a given year to get the fire season Manitoba is having.You might just need several years with “a little less snow, a little less rain, slightly drier vegetation, slightly less wet soil” that compounds over time to make a place like Manitoba increasingly at risk of more severe and earlier wildfire seasons, said Bonakdari.With soil moisture levels “among the most negative in the historical record” in early 2025, the only other thing you may need is a few a warmer-than-usual days and a spark — whether through lightning, a poorly snuffed out campfire or cigarette, or some other human error.That’s why Bonakdari would like to see more widespread use of remote sensing tech via satellites to help identify riskier zones and potentially focus on them more closely ahead of wildfire season.”We need to do some acceleration … of early warning systems,” he said. “Satellite images and AI algorithms, etc, [are] opening new windows for us to benefit from.”Climatologist Alex Crawford, who wasn’t part of the study, said there are limitations to which conclusions can be drawn by focusing on pre-conditions for fires.He also said we don’t necessarily “need AI to tell us that it was a drier April, or that there was less snow present.”Crawford, assistant professor in the University of Manitoba’s environment and geography department, was encouraged by the potential predictive value of another element of the study.”One thing we don’t have as good of information about from the weather stations that we have is soil moisture,” he said.”If we can get that from satellites, it’s … more directly relevant to how dry the plants are than say, ‘What’s the temperature? What’s the snowpack? What’s the precipitation.”ABOUT THE AUTHORBryce Hoye is a multi-platform journalist with a background in wildlife biology. He has worked for CBC Manitoba for over a decade with stints producing at CBC’s Quirks & Quarks and Front Burner. He was a 2024-25 Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT. He is also Prairie rep for outCBC. He has won a national Radio Television Digital News Association award for a 2017 feature on the history of the fur trade, and a 2023 Prairie region award for an audio documentary about a Chinese-Canadian father passing down his love for hockey to the next generation of Asian Canadians.Selected storiesEmail: bryce.hoye@cbc.caFacebookMore by Bryce Hoye

Friday, 6 Feb 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma