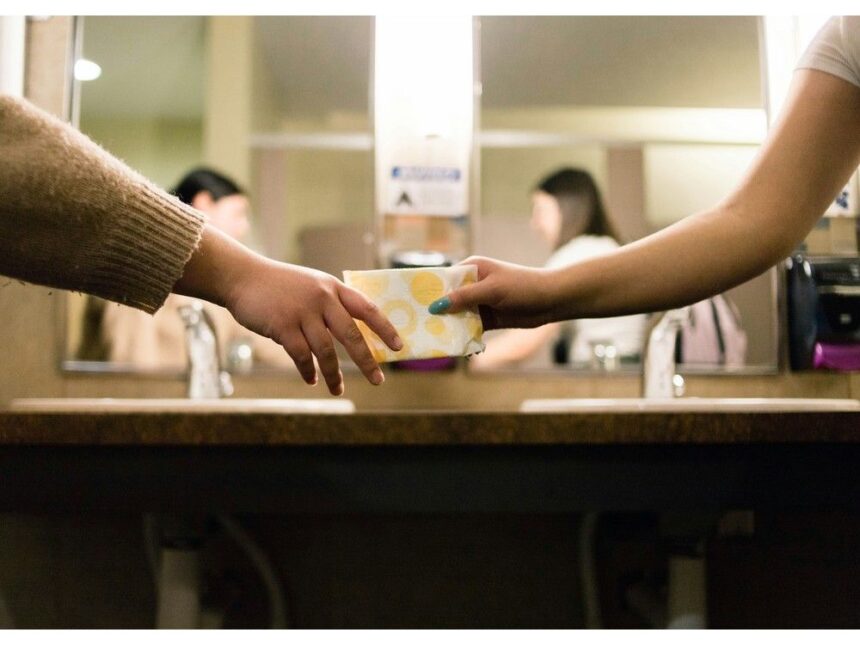

Even when women no longer need period products, they can still be victims of the pink tax as they turn to incontinence productsPublished Aug 14, 2025Last updated 7 hours ago6 minute readA patchwork of charity has emerged across the Atlantic Canada to ensure women get the supplies they need. Judith MendioleaArticle contentFor Bonnie Brayton, CEO of the DisAbled Women’s Network (DAWN) Canada, the pink tax isn’t just about tampons or contraception; it’s about who gets remembered when policy is written.THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY.Subscribe now to access this story and more:Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsSUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES.Subscribe or sign in to your account to continue your reading experience.Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsRegister to unlock more articles.Create an account or sign in to continue your reading experience.Access additional stories every monthShare your thoughts and join the conversation in our commenting communityGet email updates from your favourite authorsSign In or Create an AccountorArticle content“We are footnoted,” she said. “We don’t get funded as women, and it just gets footnoted that people with disabilities also have problem.”Article contentArticle contentBrayton calls it “the erasure of disabled women” — a systemic failure that leaves more than 30 per cent of Canadian women aged 18 to 65 without targeted policy support. For Black and Indigenous women with disabilities, that number rises to nearly 40 per cent.Article contentArticle content“We are not vulnerable,” she said. “We are vulnerabilized.”Article content Incontinence products, often used by women after childbirth or disabled women, at a P.E.I. grocery store. Judith MendioleaArticle contentOne of the starkest examples is incontinence care.Article contentWhile federal funding has been allocated for menstrual equity — including a $29.8-million Menstrual Equity Fund administered through Food Banks Canada — there is no comparable national support for incontinence products, which are essential for many disabled women or women after childbirth.Article content“If we all agree no one should have to pay for tampons, why are we fine with women paying for incontinence pads?”Article contentConvenience vs healthArticle contentIn institutions across Canada, Brayton noted, disabled women are still being given long-acting contraceptives like Depo-Provera — not for birth control, but to stop menstruation.Article content“They think it’s fine because it keeps these women from having their periods,” Brayton said. “It’s just more convenient for them.”Article contentArticle content Depo-Provera, used for birth control or to cease menstruation. UnsplashArticle contentReports from Canadian hearings and studies indicate Depo‑Provera has been administered — often unilaterally — to women in care to suppress menstruation or prevent pregnancy.Article contentArticle contentFor instance, a 2004 review by Women’s Health Protection documented “reported cases of inadequate informed consent” for Depo‑Provera, especially among women with disabilities in Ontario institutions.Article contentMore recently, a 2019 Senate report on coerced sterilization noted DAWN’s evidence that “young women with intellectual disabilities were commonly prescribed Depo‑Provera in response to family and caregiver concerns around unwanted pregnancy and menstrual hygiene.”Article contentAnd for those navigating poverty alongside disability, the math gets even bleaker.Article content“We know that women with disabilities are choosing between maybe getting their incontinence products or their menstrual products. Their incontinence products or their food, or their drugs and their food. Or their caregiver. Or their rent,” Brayton said.Article contentWhen charity fills the voidArticle contentIn the absence of clear policies or guaranteed coverage, a patchwork of charity has emerged across Atlantic Canada.Article contentThere are bins in libraries and schools. Free tampons in washrooms. Donations organized by food banks or students’ unions.Article contentSome cities stock period pantries, others rely on volunteers or nonprofits to fill the shelves.Article contentIn some rural communities, you might not find any at all.Article content Menstruation products can total several hundred dollars a month, and over a woman’s lifetime, can cost thousands. UnsplashArticle contentTo Josie Baker, executive director of PEERS Alliance, a P.E.I. non-profit dedicated to AIDS prevention, these well-meaning efforts are only a symptom of the broader failure.Article content“What we’re seeing… something like charitable initiatives happening around like people donating or getting stuff for giveaway and whatever, what that is telling us is that there is a gap, and there is a need there that’s not being met,” she said.Article contentArticle contentArticle contentWhat’s being offered?Article contentAcross the Atlantic provinces, the gap remains stark.Article contentP.E.I. has the Sexual Health, Options & Reproductive Services (SHORS) program, which covers consultation and insertion costs of contraceptives, but wait times remain long.Article contentThe province recently joined N.S. in offering free contraception through its public drug plan — including IUDs, pills and implants — but only as of May 2025.Article contentAnd according to the Drug Cost Assistance Act, these services are available only for permanent residents or citizens, leaving behind anyone living in Atlantic Canada who is under a work, study or similar permit.Article contentIn 2021, a private member’s bill — The Free Birth Control Act — was introduced in Nova Scotia’s legislature, aiming to make prescription contraception free by adding it to the list of publicly insured services.Article contentAlthough the bill only reached its first reading, it marked a growing recognition of the financial barriers many women face in accessing birth control.Article contentArticle contentN.L., and N.B. still only offer partial coverage, and only to eligible groups, such as those on income support.Article contentEven in provinces where the procedure to insert an IUD is covered, the device itself can cost hundreds of dollars unless a specific plan applies. Many women are still left to navigate private insurance with copays, denials or limited formularies.Article content A basic hormonal IUD, which can cost several hundred dollars, may not be covered unless the patient is on income assistance or enrolled in a specific drug plan. UnsplashArticle contentAnd menstrual products? They’re not guaranteed either.Article contentN.S. leads in this area, offering pads and tampons in all public schools and libraries. N.B. and N.L. followed with school-based initiatives.Article contentBut in P.E.I., the government’s 2020 promise to fund products in schools and shelters remains inconsistently implemented. Posters have been hung, but there is no documented evidence or follow-up report confirming that menstrual products are being supplied across P.E.I. schools.Article contentThe national Menstrual Equity Fund, administered through Food Banks Canada, offers some relief. But it does nothing for those who need incontinence products or require menstruation suppression for medical reasons — a frequent reality for disabled women.Article content Incontinence products, often used by women after childbirth or disabled women, at a P.E.I. grocery store. These items are not covered by most provincial drug plans. Judith MendioleaArticle contentDignity and accessArticle contentAt PEERS, that link between dignity and access comes up often — particularly for people who are precariously housed.Article content“Access to dignity is directly related to access to housing, access to money, access to things like that,” Baker said. “Certainly, like access to menstrual products.”Article contentIt’s a cascade of structural failure: when people lose stable housing, they often lose their medication routines and their ability to advocate for themselves in a system that demands paperwork and patience.Article contentBaker said this compounds the barriers already faced by those with trauma histories or intersecting identities.Article contentArticle content“Certainly, working in a low-wage position is something that no one can really afford to live on anymore,” she said.Article content“If you have a job that provides health [insurance], you probably have a better paying job… so that puts an extra tax on people that are already struggling financially.”Article contentThe cost of prescriptions, then, becomes more than a budget line, it becomes a wedge between someone and their health.Article content“We can make the most evidence-based and well-informed arguments in support of certain public health measures,” Baker said. “But if there’s not the political will, then it won’t happen.”Article contentProgress or pushed to the margins?Article contentStill, Baker sees signs of progress and a vision for what’s possible.Article contentArticle content“It wasn’t that long ago, 10 years, that women in P.E.I. were driving to Fredericton and paying $750 out of pocket for abortions,” she said. “That’s changed.”Article content Josie Baker is the executive director of PEERS Alliance. Photo by Vivian Ulinwa /Vivian UlinwaArticle contentToday, she supports universal access to sexual and reproductive care, not bound by insurance status or income.Article content“We advocate for absolutely no barriers… to contraception of all kinds,” she said. “In an ideal world, if a doctor prescribes it, people should have access to it.”Article contentBut in the real world, the system still pushes many women to the margins — and some, like Cecilia Andrade, to the exit.Article contentToday, Andrade avoids Canada’s health-care system whenever she can. She travels to Mexico for routine checkups, relying on private insurance to access care she couldn’t get publicly.Article contentJen Nickerson depends on her husband’s plan to cover contraceptives.Article contentDisabled, and elderly women pay out of pocket for incontinence products.Article contentAnd across the Maritimes, menstrual supplies are still taxed or missing from public shelves.Article content“The worst thing is that I believed him. I felt like maybe I was being dramatic,” Andrade said. “Like maybe it really was all in my head.”Article contentBut it wasn’t. It was her health — dismissed, delayed, and nearly denied.Article contentIn Canada, the pink tax isn’t just about store shelves or soap prices. It’s in the higher cost and every gap women have to navigate for access to reproductive health. One where pads and pills are no longer charity, but policy.Article contentEditor’s note: This is the second part of a two-part series looking at the pink tax. Read the first part here.Article content

Disability, dignity and the incontinence gap: Older women victims of pink tax too