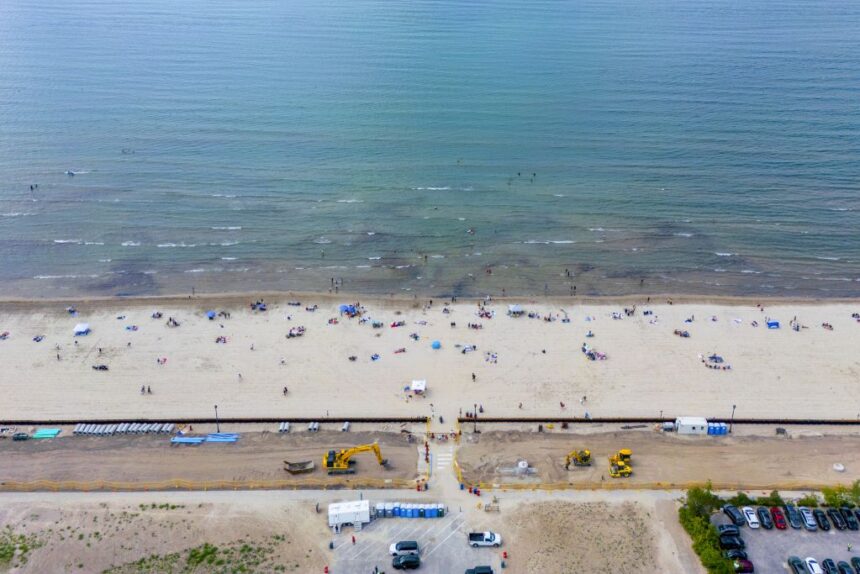

The world’s longest freshwater beach has long been dubbed Ontario’s summer playground, with 70 per cent of the population living within two hours of its shore. But on a Sunday in late August, the largest group along this 14-kilometre stretch of sand isn’t sunbathers and swimmers, it’s protesters. They drove in from Toronto and nearby towns to challenge a new provincial land-use decision that they say threatens to irreversibly harm the summer home of one of Wasaga’s regular visitors: piping plovers, the tiny, lively, endangered bird that has visited this beach every summer since 2007. If you’re lucky, you’ll get to see them bouncing like popcorn across the dunes, like I did in 2022. Over the past two decades, up to five nests (sometimes way more) have been found annually in the northeastern parts of the beach, amid the sand dunes and shrubbery that have been deemed and treated as protected habitat — meaning they can’t be raked. That protection has been possible because this 142-hectare beach is part of a provincial park managed by Ontario’s Ministry of Environment, specifically Ontario Parks, along with almost 1,214 hectares of dunes and natural land connected to it. Opponents of a plan to transfer parts of Wasaga Beach from provincial to municipal ownership gather to make their case. The proposal lacks transparency and poses environmental risks, many local residents told The Narwhal. Per its management plan, “the Wasaga Beach Provincial Park is unique in Ontario, possibly in Canada.” It is a provincial park located entirely within an urban area and for that reason, often perceived as “an unwanted monster being forced upon the town,” limiting economic growth and tourism in favour of ecological preservation and access. The provincial park’s management plan codifies this tension almost constructively, promising to help manifest “a complete, serviced resort community with extensive park facilities by stages to the year 1990.” So the plan says: “As a park within a community, it should also provide some community-oriented recreational opportunities for the residents of the resort town.” Thirty-five years later, Wasaga Beach is Ontario’s most popular provincial park, hosting more than a million visitors annually. But it isn’t the promised resort and recreation community. Wasaga Beach’s 14 kilometres of sandy shoreline offer key habitat to endangered piping plovers, as well as tourism and economic development opportunities to the Town of Wasaga Beach. The town has for years sought more control over the beach that defines it. Now, there is a provincial government in power that is listening. This summer, a maze of construction fences and bulldozers block access to the warm, shallow shore at two of eight consecutive beaches that make up the strip. The yellow and orange barriers hide colourful “Wasaga” signs and a shuttered arcade and restaurant, and a handful of food trucks sit idle in large empty parking lots waiting for the final customers of the season. But beyond all this lie the choppy waters of Georgian Bay, under a fluffy blue sky. There’s no shortage of sand and water to enjoy. But some say that isn’t enough. For years, the town has expressed frustration with the Environment Ministry’s management of the park, citing a lack of facilities, infrastructure and cleaning. Repeatedly, the town has asked the provincial government for control over the beach that defines it, most recently in November 2024. And now, there is a provincial government in power that is listening. Wasaga Beach draws more than one million visitors every year, making it the most popular provincial park in Ontario. In May, at the start of the summer, Premier Doug Ford was at Wasaga Beach to give the town $38 million to boost tourism, rebuild the beachfront and revitalize Nancy Island — a historical site in the park where the last and most important naval battle in the War of 1812 was fought. “This is spectacular now, and it’s going to be even more spectacular,” Ford said in front of the entire town council and reporters at an empty beach. Then Ford announced the province would transfer parts of the provincially owned and protected beach and waterfront to the town as part of this effort to boost tourism and economic growth, promising the beach “will remain public.” The news took many by surprise. Over the summer, residents and business owners in the town of Wasaga Beach have become concerned about the lack of transparency and details surrounding the plan. Many tell The Narwhal it all seems sudden, poorly thought out and harmful to the environment that defines their town. They also fear it could set a precedent for parts of other provincial parks to be opened for development. This move also puts us back in control of our own destiny, where we’re not beholden to day-trippers and parking lots.Andrew McNeill, the Town of Wasaga Beach’s chief administrative officer I think the current council has a plan, but they haven’t shared it. Maybe they’ve shared it with Doug Ford. Maybe it makes sense to him, but nobody’s ever put dollars and cents to it.Sylvia Bray, former deputy mayor of the Town of Wasaga Beach Adding to the concern is the timing. The Ford government passed Bill 5 shortly before the announcement, legislation that centralizes decision-making with the province, reduces environmental oversight and weakens endangered species protections. The provincial parks legislation is the last law standing to protect plover habitat. Without that in effect in Wasaga Beach, some worry these tiny, endangered birds will be without a summer home to raise their young. To facilitate the removal of 60 hectares from Wasaga Beach Provincial Park, the Ford government will have to amend parks legislation that would otherwise prohibit such a removal. The amendments haven’t been released yet, but one conservationist says he’s concerned they could enable the removal of land from other provincial parks. The plan and the precedent In November 1956, the then-Village of Wasaga Beach (dubbed “your children’s safest playground” at the time) wrote to the province of “a serious problem”: the council couldn’t stop drivers from speeding on the beach beyond the high-water mark because it didn’t control the beach; private landowners did. “There was a bit of a Wild West nature to Wasaga back then,” Ted Crysler tells The Narwhal. His family has lived here since the 1930s and he ran to represent the local riding for the provincial Liberals in the election this year. As a boy, Crysler remembers seeing cars and biker gangs drive right to the water’s edge and all along the sandy strip. Thrilling as it was to see, it wasn’t safe, and that’s what the town wanted to rectify. Former Ontario Parks employee Ted Crysler says the provincial agency does its best to maintain Wasaga Beach’s facilities and steward its sensitive ecosystem — but it’s held back by insufficient funding, he believes. At the same time, the longtime resident of the town isn’t sure the municipality will have the resources to do the job, either. “I don’t know. I don’t have the answer,” he says. “The entire area is growing rapidly since it is probably one of the finest beaches in the province,” the town wrote in the 1956 letter. It continued that developing and controlling the area was becoming more challenging, “particularly in view of the fact that the lands are not comprised within the boundaries of the incorporated Village of Wasaga Beach.” The then-council posed a solution: consider the beach as an “area from which an Ontario Provincial Park should be formed.” The province agreed and, over the 1960s and 1970s, expropriated land from local residents and businesses to form the 1,844-hectare provincial park that exists today. The park enclosed the local population of 25,000 at the shoreline and now covers a quarter of the town’s total area. Andrew McNeill’s family, one of the original settler families in the town, lost a thriving cottage business in 1974 when the park was created. In its place, the province built parking lots so “people from Toronto can come up and enjoy the beach,” McNeill tells The Narwhal. “It was a very aggressive and contentious expropriation program,” he says. “We’ve been referring to this as the Joni Mitchell approach, where back then, the province literally came in, tore down paradise and put up a parking lot.” “It was a colossal mistake,” McNeill adds. “In the process of doing that they really undermined the entire economy of Wasaga Beach. Residents and business owners, to this day, are very upset and angry with what happened.” The Town of Wasaga Beach has plans to “reimagine” about half of the 60 hectares it will receive from the province, most of which is currently paved parking lots, according to CAO Andrew McNeill. Fast forward more than 50 years and McNeill is now the town’s chief administrative officer, and a part of the push to rectify ownership of the beach. In August 2024, the town passed a unanimous motion to ask the province for a little more than two of eight beaches and surrounding lands to be transferred from Ontario Parks to the town, so they could use it to boost their local economy. In the proposal published following Doug Ford’s response this May, the province is offering the town double the amount of beach it requested: four out of eight beaches, spanning from the most eastern tip, just past the mouth of the Nottawasaga River, to 16th Street. The Ford government is doing this by amending the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, the legislation which created more than 340 parks across Ontario. It mandates the need for legislative approval to transfer more than 50 hectares, or one per cent, of permanently protected parkland, subject to environmental assessments and with ecological well-being in mind. The amount of provincial land the town is getting back is negligible, McNeill says: 60 hectares, or three per cent of the entire park. And of that three per cent, the town has plans to “reimagine” only half, most of which is currently paved parking lots that could be transformed under the town’s waterfront master plan, which hasn’t been released yet. Ontario plans to transfer ownership of more than half of Wasaga’s beachfront, outlined on the map in orange. This includes ecologically sensitive sand dunes, outlined in yellow. The Town of Wasaga Beach says the transfer is just three per cent of the provincial parkland; this calculation accounts only for the strip of the beach and omits the park areas that extend out over the water. Map: Supplied by Adam Ballah / Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition “A lot of the town’s economic objectives could be accomplished without making amendments to the [provincial parks] law,” Adam Ballah, with the Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition, tells The Narwhal. With the town only planning to develop about 30 hectares of the land it’s given, that portion is under the 50-hectare threshold codified in the law. “The province could do that tomorrow without complications.” Instead, it is making changes that could affect other provincial parks. While the amendments to the law haven’t been released in detail, there is concern any changes could make it easier to reduce park sizes in favour of unmitigated development — a stepping stone to something more. “The Ford government is being tricky in how they’re dealing with this,” Ballah says. “They’re being underhanded or not forthright. Begs the question of why they’re doing this.” No one from the Environment Ministry or Premier’s office responded to questions from The Narwhal by the time of publication. The Ford government weakened Ontario’s endangered species legislation through Bill 5 earlier this year, which means Wasaga Beach’s status as a provincial park is now the primary legal protection afforded to the piping plovers that nest there. Advocates for the tiny bird worry that if the beach’s park status is removed, there will be no legal obligation to protect the bird’s sensitive habitat. McNeill believes the law change is a means to provide a unique solution for a unique park in the town’s backyard. “We believe this makes sense for us, and in my opinion, it’s not precedent-setting,” he says. He has a litany of explanations for why the land transfer is beneficial to the town, almost all of which are financial. Ontario Parks promised to create a four-season resort destination, but it hasn’t materialized. Other beaches across the province, and even the country, are managed by local governments because “we’re closer to tourists, to issues like garbage collection, traffic, maintenance,” all traditional municipal services. Visitors come to the provincial beach but don’t really spend a lot of money in the community, leaving the town at an economic disadvantage. Plus, the provincial park took away 25 per cent of its property tax base. “We are the world’s longest freshwater beach. We need proper investment here to ensure that the product we’re sharing with all our visitors, including you this weekend, is of a quality worthy of being the world’s longest freshwater beach,” he says. “This is not about anti-environment and anti-plovers and anything anti-green. We are very green-minded.” Besides, “the actual beach frontage is a very small sliver,” McNeill says. “We’re not going to touch it.” Piping plovers returned to Wasaga Beach in 2007 after a decades-long absence. Now, the beach is “the most important and most productive nesting site for piping plovers in our province,” according to Sydney Shepherd from Birds Canada. The plovers and the park Whether you look at a map or physically stare down the stretch of sand, the amount of beach going to the town may be a sliver in shape, but a significant one at that. It is 60 per cent of the world’s longest freshwater beach, and it contains all of the piping plover habitat in Wasaga Beach. From April to August, piping plovers migrate across the Great Lakes region in search of beaches to nest on. These tiny, fluffy birds, recognizable only by their orange beaks and legs, seek out wide, undisturbed sand and gravel beaches with dunes and vegetation. As Ontario’s human population rocketed, development increased and beaches became smaller and neater. Plovers all but disappeared from the province in the 1980s. After a 30-year absence, thanks to conservation efforts in the United States, they miraculously returned in 2007, first to Sauble Beach (now Saugeen Beach) on Lake Huron, and then to Wasaga Beach a year later. Since then, according to Birds Canada, the town’s sandy shores have been home to 59 nests and 87 fledglings, the most out of any other beach frequented by plovers. The plover population that has been born on this beach makes up nearly 50 per cent of fledglings in Ontario. Many of them have gone on to establish their own nests elsewhere in the Great Lakes region. “Wasaga Beach is the most important and most productive nesting site for piping plovers in our province,” Sydney Shepherd, the Ontario piping plover coordinator for Birds Canada, tells The Narwhal. “A change in the way their nesting habitat is managed could impact the Ontario piping plover, but really has a potential to impact the population as a whole.” Inadvertently, plovers have become a part of Wasaga’s identity as much as the beach itself. The tiny birds and beachgoers have coexisted in the provincial park for 18 years, thanks to a significant conservation effort that began soon after their arrival and was formalized in legislation. Piping plovers reside in vegetated sand dunes such as these ones on Wasaga Beach. With Ontario’s weakened endangered species law, there is a concern that the dunes may not be protected from raking if they lose their status as provincial parkland. Plovers are endangered under federal law, which instructs that both the bird and its habitat be protected by Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, and in Wasaga’s case, under the provincial parks legislation. The passage of Bill 5 has effectively nullified the former. The Species Conservation Act that is meant to replace the previous law narrows a bird’s habitat to its nest, and removes protections for areas beyond it where that bird might, for example, find food. That means sand dunes that attract plovers to Wasaga Beach may not be protected against raking. Currently, plover habitat is successfully maintained by Ontario Parks officials in collaboration with Birds Canada and local volunteers, who fence off each nest and closely monitor it to ward off humans and predators. Two provincial park wardens make the rounds along Wasaga Beach. In recent years, the Town of Wasaga Beach has criticized Ontario Parks over its management of the beach, alleging a lack of facilities, infrastructure and cleaning. This year was the first in two decades where, despite two pairs of plovers creating nests on Wasaga Beach, no fledglings were born. The town noticed and used it to make the case for local management of the beach. In a series of posts on X (formerly Twitter), the Town of Wasaga Beach noted how the land transfer was a move away from “a siloed approach” that “hasn’t worked — not for the province, not for the town, and certainly not for the plovers.” “Fact: Only 2 #plovers attempted to lay eggs on our 14km shoreline this year, and none — 0 — survived natural predators, which include other protected birds (seagulls and falcons),” the town wrote on the social media platform. Many have interpreted this messaging as subtle criticism of Ontario Parks. Since the creation of Wasaga Beach Provincial Park, the government agency and the local government have worked together on building sports grounds, creating educational programs and protecting the beach. Most significantly, Ontario Parks has balanced protecting one of the most endangered birds in North America with the local needs of the busiest beach in the province.

Whats going on in Wasaga Beach? Profit, piping plovers and an Ontario towns complicated future