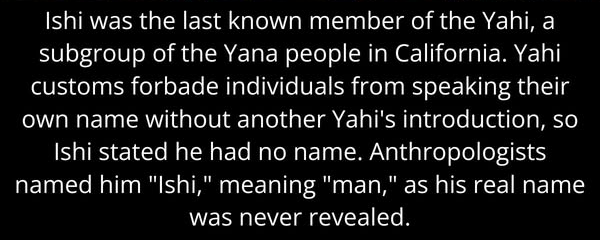

In 1911, a starving man emerged from the wilderness near Oroville, California, marking the end of an era. He was the last known member of the Yahi, a subgroup of the Yana people who had once thrived in the region before being decimated by settler violence, disease, and displacement during the California Gold Rush. Unable to live in seclusion any longer, he was taken in by anthropologists at the University of California, Berkeley. When asked his name, he replied that he had none—Yahi tradition held that one could not speak their own name unless formally introduced by another member of their tribe. With no other Yahi left to do so, he simply became “the man with no name.”

The anthropologists, recognizing the cultural weight of this, gave him the name “Ishi,” which means “man” in the Yana language. Ishi spent the remainder of his life in San Francisco, working at the university’s museum, where he demonstrated traditional Yahi crafts and shared what knowledge he could of his people’s language and way of life. His presence was both a rare ethnographic opportunity and a tragic reminder of the genocide inflicted upon Native peoples in the United States. To this day, Ishi is remembered not just as the “last wild Indian”—a term he was often labeled with—but as a symbol of cultural survival, dignity, and the devastating cost of colonization.