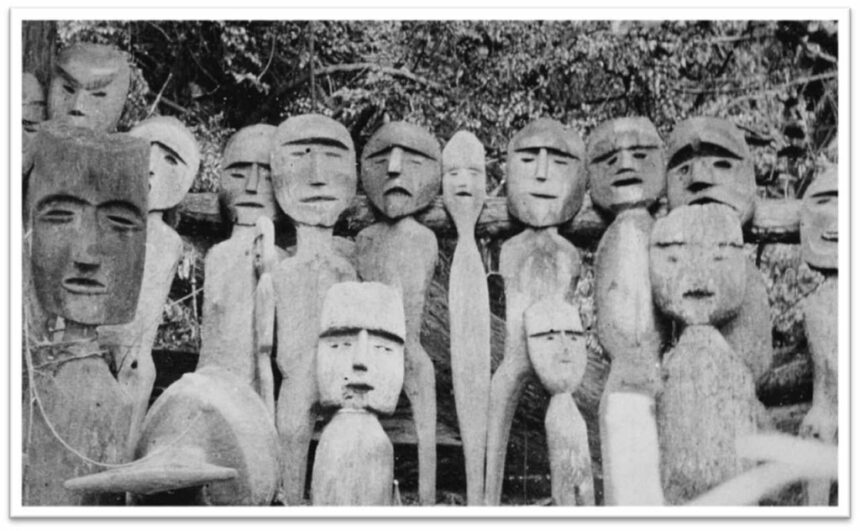

Containing 88 carved wooden human figures, four wooden whales, 16 human skulls and other components of the structure, the shrine once stood in a secret location on an islet at Yuquot. Since 1904, it has been in the storage of the AMNH. George Hunt photo This story originally appeared in Ha-Shilth-Sa here and is reprinted with minor stylistic edits. Moments after the official documents were signed, Mowachaht/Muchalaht members broke into song — marking the return of a whale hunting shrine that was held in storage at a “New York” museum for 120 years. The transfer of ownership — decades in the making — was made official on March 25 at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), which has kept the Yuquot Whalers Washing House since 1904. A Mowachaht/Muchalaht delegation of about two dozen travelled across the continent for the occasion. As the ownership was transferred back to the “Vancouver Island” First Nation, boxes and cases containing the shrine’s contents awaited their long journey back to Yuquot on the southern edge of Nootka Island, where they were taken under dubious circumstances more than a century ago. “Like other institutions right now, the museum is working to acknowledge its own history, face the past, and do so with honesty, humility, and a desire to learn,” said AMNH President Sean. M. Decatur in a statement, admitting that the repatriation is “long overdue.” Containing 88 carved wooden human figures, four carved wooden whales, 16 human skulls and other components of the structure, the shrine once stood in a secret location on an islet at “Jewitt Lake,” which stretches around the ancient Mowachaht village site of Yuquot. As a location that could only be accessed by whalers for purification rituals in preparation for the hunt, very little is known about the original purpose of the shrine. Its details are hidden by protocols in place to uphold the sacred importance to a bygone practice that once sustained the Mowachaht people and helped Yuquot become a centre for Indigenous trade and culture. ‘It is a sacred artifact that we’re dealing with’ “It wasn’t to be spoken of or displayed or anything like that,” explained Mowachaht/Muchalaht Tyee Ha’wilth Mike Maquinna, who awaits a period of helping his people understand how the whalers’ shrine should be respected. Photo by Eric Plummer “It wasn’t to be spoken of or displayed or anything like that,” explained Mowachaht/Muchalaht Tyee Ha’wilth Mike Maquinna, who awaits a period of helping his people understand how the shrine should be respected. “It will be something new for us to go through. What I feel is that it is an artifact that has a significant amount of culture, that is going to be taking place once it’s home.” The hereditary chief said it’s “still to be determined” how the shrine’s eventual resting place will be protected, but he doubts that it’s contents will ever be on display or photographed. “It is a sacred artifact that we’re dealing with,” said Maquinna. This differs from the circumstances of the shrine’s removal. In the early 1900s, a photograph was taken by George Hunt, a Tlingit-Scottish ethnographer who travelled the West Coast at the time. The whalers’ shrine, which once stood in Yuquot, has been in the AMNH in “New York” since 1904. George Hunt photo The black and white photograph appeared haunting and mysterious, with multiple human-like carvings leaning under an elaborate shelter with skulls lining the ground. Hunt showed the image to Franz Boas, who was collecting objects from the North Pacific coast for the AMNH “at a time when Indigenous cultures were threatened by decades of repressive government policies,” stated the museum. In 1903, Hunt arranged for the sale of the shrine for $500 from two Elders in the village — on the condition that the exchange took place when the rest of Yuquot’s inhabitants were away on a seal hunt. Since it came to the museum the following year, the whalers’ shrine was never on display, although a small model was exhibited until the Northwest Coast Hall underwent a major renovation in 2018. Maquinna was not part of the delegation who ventured to “New York” for the ownership transfer, but recalls travelling to the museum in the early 1990s to see the shrine’s contents. “It was mixed emotions,” recalled the chief. “It was something that I felt certainly needed to be back home, in its environment where it should be.” Some in the First Nation have long felt that a critical element has been missing from the community every since the shrine was taken. “It’s not just an artifact, but it is part of our culture — a very important part of our culture that some of us are missing: the spirituality aspect,” noted Maquinna. The shrine’s journey back home Mowachaht/Muchalaht members (from left) Marsha Maquinna and Margaretta James stand with Alex and Albert Lara during a gathering at the church in Yuquot in 2024. Photo by Eric Plummer In 1996, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht voted to formally request the shrine’s return for a future cultural centre at Yuquot. But not all agreed on how the shrine should be handled, or if it should even be touched at all. The effort received a boost last year with the involvement of Albert and Alex Lara. The father and son from southern “California” had recently discovered ancestral ties to the First Nation, based on DNA analysis and old church records that linked them to children from Chief Maquinna. Historical records indicate that a daughter and son of the Mowachaht chief somehow were transported from Yuquot to “California” in the 1790s. The Laras helped Mowachaht/Muchalaht request the repatriation of the whalers’ shrine in April of 2024. Alex Lara was in the museum with his father when the ownership was transferred. “The emotion, the awareness and just the coming together was beautiful,” recalled Alex, who helped to coordinate the complicated task of packaging and shipping the precious components back to Yuquot. The shrine’s components were loaded onto a freight truck on March 27, which made it to “Blaine, Washington” on March 31 to be welcomed with a blessing from Mowachaht/Muchalaht members at the “Canadian” border. Meanwhile, the human remains took a different journey across the continent. “The ancestral remains were put into specialized cases that were suited to be carry-on cases,” explained Alex. “Then, eight members of the delegation were escorted through special security in the airport and those were brought onto the plane with them.” Once the shrine’s components made it to “Gold River,” the plan was for some to be shipped to Yuquot by the MV Uchuck III, while other parts are lifted to the Nootka Island site by helicopter. Forty to 50 of the First Nation’s members were to assist in this effort, leading to all components being safely secured in the Yuquot church before the shrine finally returns to its original, secret location. Children play in “Jewitt Lake,” where the Yuquot Whalers’ Shrine once stood on an islet in a secret location. Photo by Eric Plummer “Once it’s in place and set back in its original site we know that nature will take its course,” said Maquinna. “Although it has been housed in the museum for many years, it doesn’t belong in a sheltered environment. It needs to be in the elements and the environment from which it came from, which is Yuquot.” The chief thanks all those who helped to bring the Whalers Washing House back home. “I’m sure that at some point in time our nation will host a dinner for all those involved,” said Maquinna.

Thursday, 5 Feb 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma