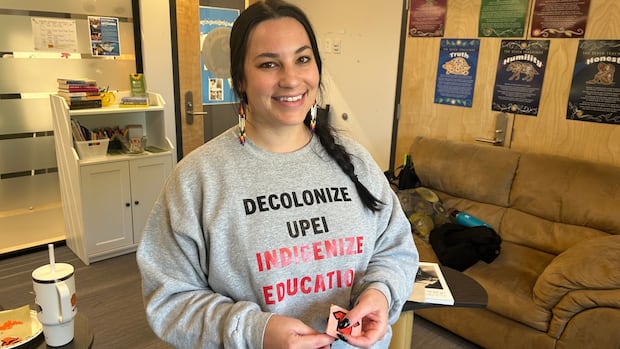

At the University of Prince Edward Island’s Mawi’omi Centre, beadwork instructor Morgan Varis carefully guides participants stitch by stitch as they create tiny orange shirt pins.”When I teach, I simply encourage people to have patience,” Varis told CBC News.”It forces you to slow down in your mind and in your body… and you’re not letting, you know, any negative thoughts creep in. You want to have positive thoughts when you’re putting your energy into your creation.”Varis, who is Cree and Acadian, also teaches as a sessional instructor with UPEI’s faculty of Indigenous knowledge, education, research and applied studies.Throughout September, she led drop-in workshops at the Mawi’omi Centre, where Indigenous students, staff and community members gathered to bead and prepare pins to wear on Sept. 30, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.”Beadwork is one of the ways that I practice my culture,” Varis said. “It’s important to share my beadwork. I feel it could be nurturing and healing for other people to learn and practice, as well as it is for myself.”This year marks a decade since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its final report and 94 calls to action.On Prince Edward Island, reconciliation has taken many forms — from passing down intergenerational knowledge like beadwork and cooking to Indigenous students carving out their own spaces on campus.Beads and belongingFor Varis, beadwork has been both a cultural practice and a personal journey.She learned the craft about 10 years ago, and said it deepened her connection to her culture and her ancestors from Peguis First Nation in Manitoba.”I feel that the beauty of beadwork is seeing all these parts come together. It symbolizes that our knowledge is beyond verbal, it’s beyond what is written down. It is shared,” she said.”Sure, it can be done individually, but it’s better when beadwork is done together and shared.”Varis says beadwork requires patience, as it encourages people to slow their mind and body and focus on positive thoughts while putting energy into their creation. (Josefa Cameron/CBC)Jolene Rolle, co-ordinator of the Mawi’omi Centre, said cultural workshops like Varis’s are important in helping Indigenous students reconnect with their heritage.”If your parent or your grandparent went to a residential school and they were cut off from their culture, they weren’t allowed to practice their traditional ways and they were made to feel ashamed of themselves,” Rolle said.”So for many people, they didn’t carry on some of those traditions with their own children because of the traumas that they faced in residential school.”The Mawi’omi Centre now offers regular opportunities to learn traditional practices, from Mi’kmaw basket weaving to beadwork, to ensure that knowledge is passed along. We’re still in an age of learning the truth…. So that all Islanders can come together on the same page.- Morgan VarisThe workshops also welcome allies.Shannon Snow, interim manager of UPEI’s experiential education department, also took part in the session that CBC News visited. Snow said it’s crucial for everyone to learn Indigenous perspectives while building stronger connections.”Being a settler on this land, it’s really important to foster good relationships,” Snow said.Varis noted that UPEI has made progress over the past decade, from establishing supports for Indigenous students and faculty to introducing IKE 1040 — Indigenous teachings of Turtle Island — as a mandatory course in 2022.”UPEI is doing well at creating spaces for Indigenous students, academics, instructors like myself,” she said. “I think we’re still in an age of learning the truth…. So that all Islanders can come together on the same page.”Sharing culture through foodFor Cree chef Ray Bear, culture is expressed through cooking.At a Fall Flavours culinary event in Rocky Point this month, Bear prepared dishes using ingredients harvested by community members in Abegweit First Nation — things like eels, striped bass and lobster.Chef Ray Bear says that when cooking for community events, he always incorporates locally sourced ingredients, such as the eels harvested and sold by members of Abegweit First Nation, shown in this photo. (Josefa Cameron/CBC)He said one of his guiding philosophies is being “one with the land” and respecting the ingredients. For example, when cooking salmon, he pairs it with local foods such as maple syrup, blueberries or native spices like sumac.”We believe what grows together goes together,” he said. “I try to incorporate that when I’m building menus.” Bear often blends traditional knowledge with the modern cooking techniques he learned in restaurants across North America and guided by the Mi’kmaw principle of “two-eyed seeing,” which brings together Indigenous and Western approaches.”That’s what we’re doing,” he said. “We’re teaching the old and the new.”Bear says his cooking follows the Mi’kmaw principle of ‘two-eyed seeing,’ which blends traditional Indigenous knowledge with modern Western approaches. (Josefa Cameron/CBC)Over decades of community events, Bear said he has deepened his knowledge by learning from elders in different Indigenous communities, from handling eel to preparing bear meat.”In probably the last 20 years, I’ve done so many community events. Every time I do it, I learn something,” he said.”That’s a great thing about Indigenous communities. People are very much willing to share their knowledge and share their experiences.”As director of culinary for Elephant Thoughts — a charity founded in 2002 to create sustainable change and deliver innovative educational programs — Bear now passes on his knowledge to future generations, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.Building community on campusAt UPEI, reconciliation also means creating spaces where Indigenous students can gather and support one another.Kallie Drummond, a Métis student in her final year of a bachelor of science degree in mathematics with a minor in Indigenous studies, said she’s seen progress at UPEI, particularly through work the Mawi’omi Centre is doing in helping students find community and navigate challenges.But she said more can still be done to better engage Indigenous students. Drummond has taken on some of that work herself as co-president of UPEI’s Indigenous Student Society.UPEI student Kallie Drummond says having spaces where Indigenous students feel secure and can practise their culture is important. (Josefa Cameron/CBC)This year, the group is planning events such as a moccasin-making workshop during Rock Your Mocs week and a Halloween film screening of Blood Quantum, a Canadian zombie thriller with a nearly all-Indigenous cast.”The more engagement we can get, then the more awareness that happens and the more acceptance that follows along with it,” Drummond said. “A lot of the times, people don’t realize some of those barriers that Indigenous people face…. So to have those spaces available to create that comfort and that security, and to have a space where you feel good about practicing your culture and being who you are is, I think, important to anyone.”

From beadwork to cooking: How Indigenous traditions are shaping reconciliation on P.E.I.