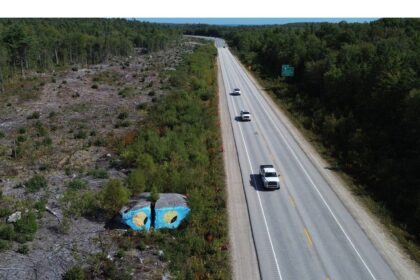

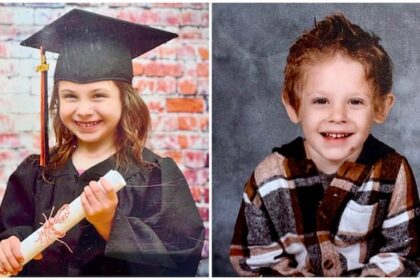

First Nations across the country are reporting the loss of funding for children’s programs after the federal government changed Jordan’s Principle rules last February. That includes Onigaming First Nation, in northern Ontario, which has been under a state of emergency since 2024 because deaths, including deaths by suicide, remain alarmingly high. “Just in the past four years, we’ve had 46 deaths. That’s roughly about 5 per cent of our population overall,” said Chief Jeff Copenace. Onigaming was running a host of programs to deal with mental health issues which included, crisis response teams, an after-hours safety team that patrolled homes and the community at night to ensure residents—especially children and youth—were safe. As well as after school programs to provide children structured support and activities outside the school day, and land-based programs aimed at keeping youth engaged and safe. Then, this year, funding under Jordan’s Principle suddenly dropped from $2.6 million to just $500,000 this year, because in February, Indigenous Services Canada changed the application system for group services. “You now need a medical note for every single child to get a service. And it’s got to be applicable specifically for what you’re applying for. And for us, it’s almost impossible,” said Copenace. “I told Canada on a call that they’re setting us up for failure.” In fact the Feb. 10 bulletin said sports events, recreation and land-based programming must demonstrate a clear link to the specific health, social or educational needs of each child in the group. “Group requests should clearly demonstrate how the proposed activity or service will benefit each First Nations child within the request,” according to the bulletin. There is no doctor in Onigaming. The nearest emergency care is in Kenora or Fort Frances, more than an hour away. Even then, wait times can stretch nearly two weeks. “To get into doctor’s appointments—it took me about 13 days the last time I got sick,” Copenace said. “For us to try to get 197 children doctor’s appointments … is just impossible.” Chief Jeff Copenace says his community lost more than $2 million in services aimed at suicide prevention. To keep some services alive, his council diverted $1 million of its own money. “We’ve decided, as a chief and council, to use our own-source revenues—roughly about a million dollars—to keep the safety patrol and the crisis response teams intact and operational,” he said. “And we need them.” Those funds are typically reserved for local priorities such as infrastructure, housing, or economic development—not emergency health programs for children. APTN News has reported similar problems elsewhere. In Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in Ontario, Chief Don Maracle said 67 Mohawk students with special education needs have been left on the sidelines, after their federally supported services were denied under the new application rules. In the Yukon, Melanie Bennett, executive director of the Yukon First Nation Education Directorate, said her organization had to shut down a rural nutrition program that had served 900 children for five years. That program provided two healthy meals a day to children from infancy to age 18, across schools, daycares, and homes. In fact, for the first time since 2020, funding for Jordan’ s Principal fell, from $1.72 billion in the year ending April 2024 to $1.64 billion for the year ending April 2025. Meanwhile, in the same period denials doubled, from $216 million to $491 million. Why the cuts happened The federal government said it made the changes to bring the program under control. Internal projections showed the cost of Jordan’s Principle approaching $2 billion. Officials also raised concerns about misuse—pointing to outlier cases like modeling headshots or sports fees. But Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, told Nation to Nation that the department always had the tools to deny inappropriate requests—and if things like modelling headshots were approved, the problem is with Indigenous Service. “Canada has always had the ability to deny claims that are not backed by professional letters and legitimate needs,” said Blackstock. “In fact, they are the ones raising the modeling headshots that they approved. So the question should be asked, why did they approve it if it wasn’t legitimate?” “Second of all, it’s very dangerous to rule out whole categories of services for kids.” Cindy Blackstock, executive director, Child and Family Caring Society Entire categories were cut off The Feb. 10, operational bulletin made it clear that many services that had once been eligible under Jordan’s Principle would no longer qualify. That included things like environmental and home repairs, renovations or modifications. In the bulletin, ISC said, it also determined “based on its analysis of legal obligations related to substantive equality” that it would not fund School-related requests, “unless linked to the specific health, social or educational needs of the First Nations child.” As the program rolled out two families who were looking for these services under Jordan’s Principle engaged a pro-bono lawyer to take their cases to court. Two families are now in court Two families impacted by the changes have been fighting in court and a decision on the Powless case is expected any day, In 2022, Joanne Powless, a grandmother from Oneida Nation of the Thames near London, Ont., applied for about $200,000 through Jordan’s Principle to fix the severe mold in her home. Powless is the primary caregiver for her two granddaughters, both of whom have asthma that doctors say was caused and worsened by the poor living conditions. Her application included letters from a pediatrician and an environmental health officer who warned that the situation posed a serious health risk. But ISC denied the request, arguing that major home renovations fall outside the scope of Jordan’s Principle. Powless challenged that decision in Federal Court and won earlier this year. The judge found the department had taken an “unreasonably narrow approach” by treating the request solely as a housing repair, rather than as a health issue affecting two children. On Oct. 6, Canada appealed the ruling, and a new decision is expected any day. The other case involves Scarlet Culley, a five-year-old autistic girl in Thunder Bay who was cut off from her ABA therapy sessions. Her support had been covered through Jordan’s Principle until she was suddenly denied. “Essentially… rather than looking at the children’s actual needs, there’s a categorical exception being applied at the outset,” said David Taylor, the lawyer representing both families who appeared on Nation to Nation with Blackstock. “It’s a kind of broad measure that has affected these two families in very different circumstances.” And while the government invoked “substantive equality” as its rationale in the Cully case, Taylor says it has failed to define or apply that concept meaningfully. Blackstock agreed. “What we know from access to information documents that we obtained is that at the time when Canada would have written this letter saying it’s because this family did not meet substantive equality … they had no definition of substantive equality,” she said. “So again, it really raises serious questions whether this is actually a meaningful effort to follow the law … or simply a way to use it for cost cutting.” Minister acknowledges the damage ISC Minister Mandy Gull-Masty, says Jordan’s Principle is one of her top priorities Minister of Indigenous Services Mandy Gull-Masty, who took office after the bulletin was released, said she’s working on a new plan under a Dec. 20 deadline imposed by the courts. “It is one of the challenges that the operational bulletin, I think, unintentionally created. I don’t know if everybody is aware that if you live in a remote isolated community where the doctor flies in periodically, well maybe they don’t have the resources to meet, you know, what was probably viewed as a very reasonable paper trial process, she told Nation to Nation. “I want to make sure that I’m able to offer those accommodations right now with the way that the principal is written. I don’t have that authority.” Gull-Masty said she’s planning a broad engagement process to reshape the program with input from communities, families, and service providers. “I have started this process this year where I’ve done a lot of engagement. I’ve had some very high level conversations internally within my team, within the department. I’ve asked for them to start having a strategy,” she said, “We’re trying to nail down and really finalize what those next steps are going to look like. But I think it’s gonna be a mixed pot. It’s gonna be working with the community, it’s gonna be reaching out to those important families who are users of this program. It’s going to be working with the organizations who implement this program.” In the meantime Copenace has asked Indigenous Services Canada to prioritize his community as it is under a state of emergency. He said some officials visited in September to examine the problem with the application process, but no changes have happened yet. Data notes: Data is limited to approved original determinations. Appeals and re-reviews of past decisions are excluded. Inuit requests and service coordination requests are not included. The financial information included in this analysis is based solely on approved amounts captured in Jordan’s Principle CMS, and may not reflect actual expenditures and/or match coding from Systems, Applications, and Products. Continue Reading

Theyre setting us up to fail: Did the changes to Jordans Principle go too far?

Leave a Comment