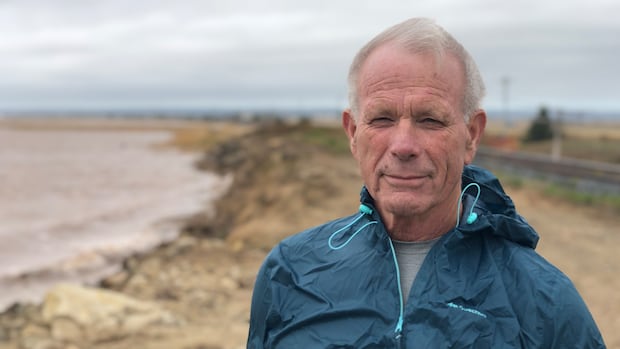

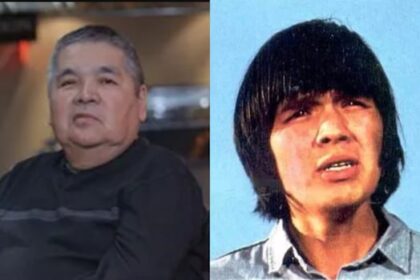

New Brunswick·NewThe protection of the Chignecto Isthmus is on track for completion in 2035. That’s right around the same time that an astronomical tidal cycle hits its peak, increasing the chance a storm surge will cause flooding in the valuable corridor and neighbouring communities.Astronomical cycle means higher high tides expected until mid-2030sErica Butler · CBC News · Posted: Oct 20, 2025 5:00 AM EDT | Last Updated: 1 hour agoRetired emergency management co-ordinator Mike Johnson recalls Bay of Fundy waves lapping the railway tracks at Aulac in October 2015. (Erica Butler/CBC)Governments have long known the low-lying Chignecto Isthmus is under threat from climate change. Officials say the protection of the critical corridor is now underway, scheduled for completion in 10 years. But during that time, an astronomical cycle is playing out, creating bigger tides in the Bay of Fundy and increasing the vulnerability of the infrastructure and communities on the isthmus.The 18.6-year-long lunar nodal cycle is one of the many patterns tracked by warning preparedness meteorologist Bob Robichaud, with Environment and Climate Change Canada. “At any given time, at a high tide in the Bay of Fundy system, there could be some flooding if there is a significant storm creating a storm surge,” says Robichaud. “The vulnerability increases when we reach the peak of that 18-year cycle.”WATCH | Timing is everything, says expert:Lunar cycle will bring higher tides to vulnerable Chignecto IsthmusProtection of the Chignecto Isthmus is on track for completion in 2035. At the same time, an astronomical cycle is increasing the strength of the Bay of Fundy tides — and the chance a storm surge could overtake the current dike system. Robichaud last flagged the impact of the lunar nodal cycle in 2015, when it hit its previous peak. Since then, the cycle has been on a downward trend, dampening the strength of tide cycles, even obscuring the effect of rising sea levels in the past decade.“Now we’re back on the upward trend,” Robichaud said. “It looks like the next peak of this 18-year cycle is going to occur at various times between about 2029 and 2036, with 2034 being the probable time when the peak tides are going to be observed.”10-year plan for protectionNew Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the federal government first decided to commission an engineering study to look at solutions for the isthmus in 2018. The study wasn’t released publicly until March 2022. It came with a 10-year estimated timeline and a price tag of between $190 and $300 million. Three and a half years later, the timeline remains unchanged at 10 years, but the price tag is now estimated at $650 million. It could be a small price to pay to protect a corridor that includes high-voltage transmission lines, CN Rail tracks and the Trans-Canada Highway. Each day, an estimated $250 million in trade depends on the isthmus transportation corridor, according to a recent presentation by New Brunswick and Nova Scotia officials.Even with those high stakes, the provinces and the federal government have spent the past few years squabbling over who will cover the cost of fortifying the corridor. That fight was settled in March 2025, when both provinces committed to paying $162.5 million each to support the project, matching the federal government’s $325 million commitment. Hurricane modelling not yet releasedKelly Cain, deputy minister of New Brunswick’s Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, told a legislative committee on Oct. 3 that the protection of the isthmus is, “a daily file, a daily meeting happening in our department with someone, whether it’s the feds or the Province of Nova Scotia.”The project remains in planning stages. Engagement with First Nations is ongoing, as are consultations with other stakeholders and environmental groups. Projections of what will happen with Bay of Fundy tides and storms are also on the group’s radar. “We have done some hurricane modeling,” Cain told the committee. “I have read it, and there are threats around that … it’s several years down the road. It’s not immediate.” The project to fortify the Chignecto Isthmus is a ‘daily file,’ according to Kelly Cain, the deputy minister of transportation and infrastructure. (Jacques Poitras/CBC)DTI director of communications Jacob Hoyt would not share the hurricane modelling report, but said via email that it was completed by the Natural Research Council of Canada, which will eventually release it.While the next peak of the lunar nodal cycle is slated for sometime in the mid 2030s, the amplifying effect on tides will increase incrementally until then, meaning higher high tides each year. Combined with an incremental sea level rise each year, that means it will take a “lesser storm” to result in coastal flooding, Robichaud said. Picture worth a thousand warningsDuring the last lunar nodal peak in 2015, Robichaud looped in then-EMO co-ordinator for Cumberland County, N.S., Mike Johnson. The two made a trip to the dikes near Aulac in September 2015. Johnson returned a month later to observe the tides during a 60-centimetre storm surge to get phtographs for Robichaud.And boy, did he get a photograph. The combined high tide and storm surge brought the water right up to the edge of the CN Rail line.Former EMO co-ordinator Mike Johnson captured this image of VIA Rail’s the Ocean passing through Aulac, N.B., during a storm surge in 2015, with a higher-than-usual high tide caused by the lunar nodal cycle. (Submitted by Mike Johnson)Johnson recalls seeing the wind “catching the waves and throwing the water up against the railway tracks.” As he was preparing to leave, VIA Rail’s the Ocean made its way along the track. Johnson caught the passing of the train on camera and shared the image with then-Nova Scotia MP Bill Casey. The photo has since become iconic of the tidal threat to the valuable corridor. Timing is everythingDespite how close the water came in 2015, there was no flooding of the corridor that year. Robichaud said ultimately, a breach of the dikes is a high-stakes but low-probability event.He said it all comes down to timing. So if a storm surge comes at low tide, the effects may not even be noticeable. “But if things were to line up,” Robichaud said, “it definitely would be a serious situation there.”That’s why it’s important to keep track of the timing of storms and tides, he said. When Robichaud walked the dikes in Aulac in 2015, he found something that has become a personal reminder for him — an old railway spike from the CN tracks. Warning preparedness meteorologist Bob Robichaud keeps this railway spike as a reminder of the vulnerability of Chignecto Isthmus infrastructure. (Erica Butler/CBC)“I keep it on my desk as a reminder of the potential vulnerability there,” Robichaud said. “I’m very in tune to monitoring these systems … When there’s potential for storm surge, that’s one of the first things that I look at, is whether things are going to be timed in such a way that there could be issues.”ABOUT THE AUTHORErica Butler is a reporter with CBC New Brunswick. She lives in Sackville and works out of the Moncton newsroom. You can send story tips to erica.butler@cbc.ca.

Fundy tides to peak in 2034, adding urgency to Chignecto Isthmus flood project