Canada·First PersonEvery family holds onto special dates. For Ban Zhang, moving to Canada meant learning about its history — and reconciling the significance of those holidays that once seemed distant and foreign and making them markers of his own identity, memory and belonging.The holidays I didn’t grow up with taught me the true meaning of being CanadianBan Zhang · for CBC First Person · Posted: Nov 11, 2025 4:00 AM EST | Last Updated: 4 hours agoListen to this articleEstimated 5 minutesThe audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.Every family holds onto special dates. For Ban Zhang, moving to Canada meant learning about its history — and reconciling the significance of holidays, such as Remembrance Day, which once seemed distant and foreign and making them markers of his own identity, memory and belonging. (Katie Carey/CBC)This First Person column is by Ban Zhang, who lives in Vancouver. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.Every family holds onto special dates. My family of three landed in Vancouver in November 2000. Our son had just started Grade 1. As the plane descended, sunlight spilled through the cabin windows. What we didn’t realize was that our arrival coincided with the eve of Remembrance Day in Canada.The next morning, still fighting jet lag, a friend took us for a walk in a local park. Crowds were gathering — men and women, children, veterans in uniform — each wearing a small red flower. I asked my friend cautiously, “Is that an opium poppy?” My friend corrected me gently: “It’s the Remembrance Day poppy.”In Chinese, the word my friend used — “Yumeiren” (虞美人), refers to a beautiful flower, symbolizing hope as the flowers are annuals. One reference is to Consort Yu (虞姬) who died by suicide so her husband Xiangyu (项羽), the Conqueror-King, wouldn’t be distracted by their love on the battlefield and these flowers grew where her blood spilled. It also refers to a Chinese classical poetic term (Cipai), including one poem where an emperor expresses his deep sorrow and nostalgia for his fallen kingdom. At that moment, I realized it wasn’t the flower I had mistaken, but the world of meanings around it. For Canadians, the poppy symbolized sacrifice, war, peace and loss. For me, it evoked a sense of poetry and sorrow. Two cultures, two symbolic systems, all pinned to the same red bloom.Later, I read in a local Chinese-language newspaper that more than 81,000 Chinese labourers who crossed Canada on their way to Europe had been recruited to the Allied war effort during the First World War. The men who formed the Chinese Labour Corps dug trenches and worked behind the lines. Many never returned. Only a few received ranks or medals, while for most, there was not even a gravestone. Yet perhaps the poppies bloomed for them, too.Poppy and Yumeiren look similar but have different meanings in Chinese and Canadian cultures, says Zhang, who snapped this photo of the flowers in his Vancouver neighbourhood. (Ban Zhang)That day taught me my first real lesson as an immigrant: holidays — even though I didn’t personally feel a sense of connection to them — are not just about time off or celebration. They are reminders of history and carriers of collective feeling.As we settled in, more “Canadian” days appeared on our calendar. Not long after, our son ran home, beaming: “No school tomorrow. It’s Pro-D Day!” We had no idea what that meant. Only later did we learn that it stood for professional development day, when schools close so teachers can receive training. At first, it felt like a disruption. Over time, we came to see it as a marker of a different educational philosophy — less about cramming knowledge, more about supporting teachers and giving families time together.Then came July 1. For us, that date had always meant something else — the founding anniversary of China’s ruling party in 1921 or the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return in 1997. But here it was Canada Day.Zhang, centre, and a family friend, with a group of people celebrating Canada’s 150th anniversary of Confederation at Canada Place in Vancouver in 2017. Some of the faces have been blurred since they were strangers who Zhang met at the event. (Submitted by Ban Zhang)We joined the celebrations at Canada Place: the sea of red and white, the music, the fireworks exploding over Vancouver’s night sky. It felt joyous, yet I couldn’t help remembering another story. For decades, Chinese Canadians had called July 1 “Humiliation Day,” because on that very day in 1923, the Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect, banning all Chinese immigration. In 2023, a century later, I stood on Parliament Hill in Ottawa with Chinese Canadians from across the country to mark that painful centenary. Mary Simon, Canada’s first Indigenous Governor General, unveiled a plaque in the Senate. The next day, we gathered in solemn commemoration.I stood shoulder-to-shoulder with families who had been here for generations. Though we had arrived much later, we shared the moment of remembrance. We were no longer outsiders.Zhang, left, at the unveiling of a plaque in Ottawa acknowledging the impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act on Chinese Canadians. He’s standing next to the Senate’s Usher of Black Rod J. Greg Peters. (Submitted by Ban Zhang)Other holidays marked our family’s growth more intimately. When our son was young, nothing excited him more than Halloween. Year after year, he dressed up, carved pumpkins and went door to door. Now he works at an animation studio. One Christmas, his first after starting work, he handed us not candy but wrapped gifts: a massage device for his mother, a back cushion for me. He had just been promoted at work. I will never forget his look — shy, serious, quietly proud. In that moment, I saw that he had found his place, and in doing so, helped us find ours.Behind every holiday lies a society’s way of measuring time. Behind each family celebration is a record of growth. From the solemnity of Remembrance Day to the warmth of Christmas dinners, from the confusion of Pro-D Days to the fireworks of Canada Day, we have walked slowly from unfamiliarity to belonging.People often ask me why we chose to immigrate to Canada. Once, I would have spoken about education, environment or opportunity. Now, my answer is simpler: we came for the holidays. We came so that in festivals that were not originally ours, we could gradually find our place.Holidays are not destinations. They are waypoints — reminders of where we come from and gentle guides toward where we are going. Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.

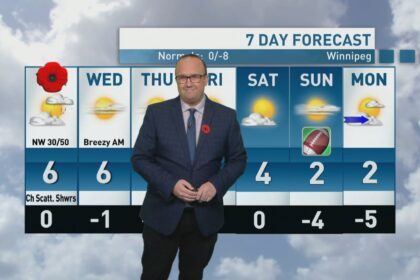

Moving to Canada meant new holidays and finding my own place within them