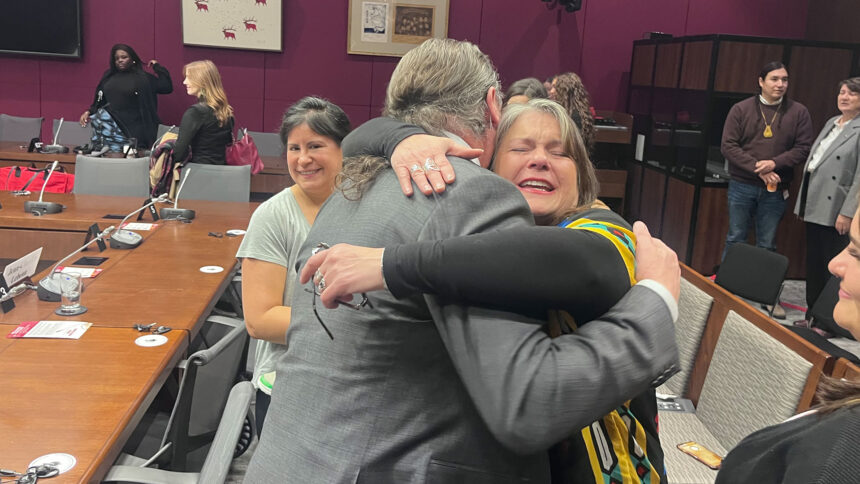

A Senate committee has voted ten to one to pass sweeping amendments to the government’s Bill S-2, ending what’s known as the second generation cut-off and implementing a one-parent rule, that allows anyone with status under the Indian Act to pass their legal identity and rights on to their children. The vote on Tuesday by members of the Standing Committee on Indigenous Peoples came despite repeated pleas from Indigenous Services Minister Mandy Gull-Masty to pass the bill as is. Dawn Lavell-Harvard, a former president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada and a proponent for such changes, sat in the committee room to watch the vote. The moment the committee passed the amendments, she pulled out her phone in the public gallery and texted her mother, Jeannette Corbiere Lavell—who, 50 years earlier, had taken the government to court after losing her status in 1970 for marrying a non-Indigenous man. Corbiere Lavell won that case, but it did not fully end discrimination in the Indian Act. “She said she’s sobbing at home, hearing this go through,” Lavell-Harvard, teary-eyed, told APTN News, her own voice trembling. “And I told her, I could barely hold it together in the room, myself. I should not have worn mascara.” Those were tears of joy for a mother and daughter who had been fighting for these changes for half a century. “This is historic. This is for all of our babies and all of those children. I can’t believe I’ve witnessed this go through,” she said. ‘We cannot govern who First Nations fall in love with’ Mi’kmaq Senator Paul Prosper at the Standing Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples The amendments were introduced by Sen. Paul Prosper, a Mi’kmaq from Paqtnkek First Nation and former regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations, after the committee heard from 57 unique witnesses and received 47 written briefs. “I chose to champion this amendment because I believe there is nothing more vital to the survival of First Nations than this change,” Prosper told the committee. “The fact is that we cannot govern who First Nations fall in love with. This change says, love who you love and do not worry because your children will not fall by the wayside.” Those calling for immediate action included the Assembly of First Nations and the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. Every Mi’kmaq chief in Nova Scotia also sent letters of support for the amendments. All but two witnesses who appeared before the Senate urged them to end the second generation cut-off. Those two witnesses did not object to the amendments, they only expressed worry that changes might delay the bill’s passage—a concern most senators ultimately dismissed. Individual advocates, women’s rights experts, lawyers, and survivors of status loss also testified in favour of ending the second-generation cutoff now. Many of them criticized the government for taking years to address the issue, doing so piecemeal, and only when forced to by court decisions. Bill S-2 was introduced to satisfy a court ruling in the Nicholas case. It aims to restore Indian status to a limited group of 3,000 to 5,000 people affected by historic enfranchisement provisions, including individuals who gave up their status voluntarily for a variety of reasons, including to keep their children out of residential schools or to vote in federal and provincial elections. Some also lost their status under outdated rules that stripped First Nations individuals of legal recognition if they obtained a university degree. The amendments passed by the committee propose to go much further. They remove the second-generation cutoff and replace it with a “one-parent rule” for determining status—potentially impacting tens of thousands of people. Under the amendments passed by the committee if one parent has status, their children will have status. This replaces the current system, where legal recognition is severed after two successive generations of intermarriage with non-status individuals. The change could restore legal status and rights to entire generations who were previously excluded. Read More: Mandy Gull-Masty calls Senate’s push to end the second-generation cutoff ‘racism’ Senator proposes major amendments to end second-generation cutoff Senate tables legislation aimed at fixing ‘Indian status’ inequities Sen. Kim Pate said this is now the 5th piece of legislation the government has passed since 1985 to satisfy court rulings—yet it still hasn’t eliminated discrimination in the Indian Act. “We cannot, in my humble opinion, be responsible for continuing discrimination we know is currently in the Indian Act and will continue if we pass this bill as it currently reads,” said Pate. ”We have an obligation as senators to represent the interests of those who aren’t otherwise represented by elected officials, sometimes referred to as minority issues. This, to me, is clearly one of those moments where we must stand up in support of those groups.” Others recalled testimony warning that, if left unaddressed, the second-generation cutoff will ultimately lead to the legal extinction of First Nations. “How can the government speak about the critical importance of reconciliation when the eventual result of the second-generation cutoff will be a drastic decline in the population, eventually leading to extinguishment (of rights)?” asked Cree Sen. Mary Jane McCallum. “ As a senator, I have a responsibility to create entry points for First Nations who have been excluded to make their way back respectfully, timely, and not at the whim of a Prime Minister through a minister.” Prosper echoed that concern, framing the cutoff as a continuation of colonial policies designed to erase Indigenous identity. “This change stands up against a policy of extinction and embraces the lost generations who, despite it being their birthright and being known and claimed by their communities, cannot access the programs and services that are only made available to those with a piece of paper that says they have status,” he said. Sub: Amendments won’t stop consultation says Audette Innu Sen. Michèle Audette supported amendments to S-2 Gull-Masty, who is Cree and a member of the Waswanipi Cree Nation in northern Quebec, appeared twice before the senate during its study of S-2. Both times she urged the Senate not to amend the bill. Gull-Masty argued that expanding the bill without proper consultation could jeopardize constitutional obligations, particularly the duty to consult with First Nations on issues that affect their rights. She called attempts to amend the bill without broad consultation ‘racism itself.’ Lori Doran, director general at Indigenous Services Canada appeared before the committee on Nov. 18 as it considered the amendments and explained that the minister had launched a multi-stage consultation process co-developed with First Nation partners. Gull-Masty told the committee that full consultations on the second-generation cutoff will start in 2026. Doran emphasized that the consultation was not about “whether” to end the cutoff but about “how” to do it—adding that they expect to report back with findings as early as December. Innu Sen. Michèle Audette, who introduced the bill in the Senate on behalf of the government, said that in that case, the amendments passed by the Senate should not prevent the minister from moving ahead with consultations. Drawing on her decades of advocacy and her experience as a former commissioner of the national Inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, Audette told APTN, “I can say officially that the system is not on our side…today we have an opportunity, and we cannot miss this opportunity. “I believe in the person,” Audette said of Gull-Masty. “But it’s the machine around her. It’s the system.” Senate amendments are not final Dawn Lavell Harvard and other witnesses showed up to watch the vote, which she described as ‘historic’ Although the Senate committee passed the amendments, the bill must still move through several stages before it becomes law—including the report stage and third reading in the Senate, followed by three readings in the House of Commons and stops in the committee. At any of these points, the amendments could be challenged, revised, or removed altogether. Audette said she thinks it’s likely that will happen. “ So this is where I think it’s very important that every citizen, every woman, men, youth, elders, chiefs – people who told us that we need to go further, we need to do more – it’s time for them to speak to the other chamber. ” Lavell-Harvard is among those who pushed the Senate to make these changes. “ I think what was said here today was really clear. You have two choices. You either say yes to these amendments, you say yes to a one parent rule and yes to ending the second generation cutoff, or you’re saying yes to the extinction of First Nations people,” she said. . Tags: First Nations, Indian Act, Indian Status, Legal Status, one parent rule, Ottawa, Parliament Hill, S-2, Second generation, second-generation cut off, Senate, Treaty Rights Continue Reading

Senators vote to end the second-generation cutoff for status Indians

Leave a Comment