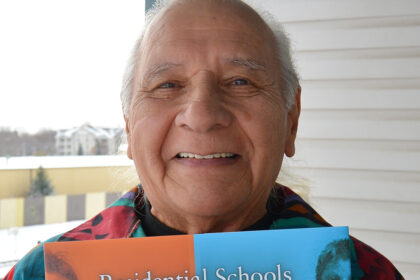

Canada·First PersonBailey Ross has devoted himself to speaking French and promoting Acadian culture. But feeling like he belonged and could call himself Acadian came much later in life. I’m fluent in French but belonging feels more complicatedBailey Ross · for CBC First Person · Posted: Nov 23, 2025 4:00 AM EST | Last Updated: 3 hours agoListen to this articleEstimated 6 minutesThe audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.Bailey Ross has devoted himself to speaking French and promoting Acadian culture. But feeling like he belonged and could call himself Acadian came much later in life. (Submitted by Bailey Ross)Sometimes one little word can make you feel like an outsider. I had been talking about the importance of defending Acadian rights with a francophone politician seated at my table during a social event. It was a great conversation that left me feeling prouder than ever of being Acadian. Alas, my excitement was quickly extinguished in the final seconds of our interaction. As he got up to leave, he asked me where I was from.“I can’t pinpoint the accent. You say ‘faque’ like a Quebecer, but you also sound Acadian.”Most francophones can uncannily pinpoint your place of origin with near military accuracy by the most subtle phonetic sounds. I had said faque (which translates to roughly “so” or “therefore”) in a way that stood out to him.I replied with my scripted, theatrical response: “I’m an anglophone so my accent is a hybrid creature sculpted by the many accents of my friends and educators who have helped me along the way.” And, in typical francophone style, his response was, “Oh wow! You have a great accent for an anglophone.” That backhanded compliment, whenever I get it, always leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Although I have been immersed in Acadian and francophone culture since I was five, my journey to find my place within it has been more complicated.My hometown of Digby, N.S., is primarily an English-speaking community, but it has a French immersion program that goes all the way to Grade 12. My parents put me into this program because they believed learning a second language might open doors for me. While I didn’t feel a strong affinity at first, something about the language and culture clicked when I was in high school and inspired me to pursue my post-secondary education in French. Before I knew it, my life was entirely lived in French. I went to a francophone university, so all my courses were taught in French and everyone spoke French on campus. I could order my tea at Tim Hortons in French and I could even play curling in my second language. Ross, left, along with other student union colleagues at the l’Université Sainte-Anne organized a federal election candidate debate for the West Nova riding in 2019 in French. (Submitted by Bailey Ross)This was a revelation: I finally got to experience French where it was just the way people naturally chatted rather than the controlled environment of a classroom. I got involved in more organizations that advocated for the French language, francophone culture and Acadian rights in Atlantic Canada and I soon was hired as a teacher in a French school. I started to feel the urge to call myself an Acadian — that’s how strong my affinity was — but I didn’t want to appropriate an identity.When I brought up my feelings with my family, I learned I have distant Acadian genealogical roots. My great-great-grandmother was an Acadian from Clare, an Acadian region of Nova Scotia. However, once she married an English-speaking husband, the language ceased to be used in our family. Upon digging more into Acadian history, I learned to my delight that the Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (the Acadian Federation of Nova Scotia) has established a definition clearly outlining who can bear such an identity. According to it, the Acadie of Nova Scotia is not defined only by its 12 designated Acadian regions, but it equally includes those who contribute to the development of the Acadian community with the goal of preserving its language and its culture. At last! I finally had an answer. With my newly discovered familial roots and a textbook definition that clearly fits my profile like a glass slipper, the answer was evident — I’m an Acadian! WATCH | A theatrical crash course in Acadian history:Acadictionnaire: A new, bilingual look into the ABCs of Acadian historyA first of its kind at Le Pays de La Sagouine, this 25-minute play takes audiences through the terms that represent Acadians for a crash course in the culture.I began to think of myself proudly as such. But as quickly as my decision was made, it was rescinded.Somehow, calling myself Acadian was a lot harder than I had anticipated.Although I’ve devoted myself to Acadian culture, my mother tongue — English — represents a population that expelled Acadians from Atlantic Canada beginning in 1755.I feared being an unsettling presence for Acadian-born folks or to be considered a token Acadian who was jumping on the bandwagon. I also don’t speak Acadian French from one specific place.

I’m an Acadian at heart even if my accent marks me as an outsider