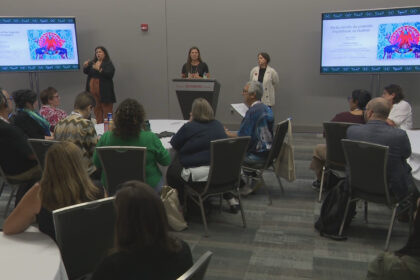

In their last meeting of 2025, the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table planned action items to heal and preserve the area’s siwɬkʷ (water) y̓ilmixʷm (Chief) kalʔlùpaɋ’n Keith Crow of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band participates in discussions during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands at the Lower Similkameen Indian Band (LSIB) office on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens y̓ilmixʷm (Chief) kalʔlùpaɋʹn Keith Crow says the Similkameen River is being failed by those tasked to care for it, and more must be done to protect the waterway for future generations. The river “has been black for the last month,” he told a room full of regional officials in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands on Nov. 21. “(The Similkameen River) is where our name comes from. It’s who we are,” Crow added. “And we’re failing it.” Crow — the chief of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band (LSIB) — made the comments during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table. The group consists of more than 20 elected syilx leaders, mayors and other regional government officials from throughout the region. It was their sixth formal meeting since 2023, and their second since signing a memorandum of agreement (MOA) last November, which solidified their commitment to protecting the region’s watersheds. ‘I blame that on the mine’ An aerial view of the Similkameen River flowing through the town of Keremeos in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands in December 2024. Photo by Aaron Hemens Crow said, when he was a kid, people could swim in the river without any fear of getting sick from the water. “You didn’t worry about taking a swallow of water — it didn’t matter,” he said. “Now, you better keep your eyes closed, because it’ll burn when you come out of the water.” The Similkameen River’s water levels and quality has been impacted in recent years due to a number of cumulative effects: from mining, to farming, logging and the impacts of climate change, such as drought and wildfires. Crow hopes his granddaughters can experience a healthy river when they’re older, he added, which is “not very long away.” “I’m just hoping that in the next 30 years, we still have a river,” he said. LSIB Elder Rob Edward told leaders that he hasn’t been able to fish out of the Similkameen River since 1982. “That’s a long time, not to have a ceremony for the fish,” he said. “A ceremony for gathering — even drinking the water is a ceremonial process.” Edward said, in terms of water quality declining: “I blame that on the mine,” he said. “But you also gotta look at farming.” The Copper Mountain Mine is located in smǝlqmíx and syilx territories near the town of “Princeton.” It falls within the homelands of LSIB and Upper Similkameen Indian Band (USIB) members. Hudbay Minerals owns and operates the mine, and are in the process of seeking to expand its operations by reviving the mine’s old Ingerbelle Pit. If the expansion is approved, it would add 10 years of mining to the overall operation, extending its life to 2037. The end of the Copper Mountain Mine’s old Ingerbelle pit, bottom, located below the Similkameen River in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands, in November 2024. Photo by Aaron Hemens In June, Crow told HudBay officials that the LSIB community still “does not consent” to the mine’s proposed expansion. smǝlqmíx Youth have also launched a social media campaign that rejects the mine’s proposed expansion. Spencer Coyne, the mayor of Princeton, said at the meeting that the Tulameen River — a tributary of the Similkameen River that runs through town — is so dry in the summer that “you can walk across it without getting wet.” “In some spots, it’s gone completely. The Similkameen’s not much better,” said Coyne. “Keith and I grew up together. Where we swam as kids — it’s up to my knees now, where it used to be over our heads. It’s ridiculous. “I want to see the health of our river back. I want to see those lakes back.” However, Coyne endorsed a letter in August from the Regional District of Okanagan-Similkameen to the province that expressed support for the mine’s expansion. “This is a letter of support to get the process moving,” Coyne is quoted in an article by the Vernon Morning Star. “It’s been going on for years. We just want to see some movement.” Princeton mayor Spencer Coyne, left, and Chief Keith Crow of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band listen to discussions during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens ‘We need to think long-term’ At a previous meeting in May, the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table began early talks of developing a 250-year-plan to protect water in the Okanagan-Similkameen region’s watersheds. The November meeting saw the establishment of two working groups. One was formed to develop policies that strengthen the organization’s governmental structure, and the other is focused on creating on-the-ground projects that address critical regional siwɬkʷ (water) concerns. The creation of the two working groups represent “a pathway to move from discussion to action,” said y̓ilmixʷm (Chief) simo Robert Louie of Westbank First Nation. “They align with our shared principles; support the 250-year vision that we discussed,” said Louie, who is the co-chair of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table. “This is our objective, is that we need to think long-term.” y̓ilmixʷm (Chief) simo Robert Louie of Westbank First Nation participates in discussions during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands at the Lower Similkameen Indian Band (LSIB) office on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens Policy and knowledge gaps The establishment of the governance working group stems from concerns raised by the organization’s members about “fragmented” water governance policies that “limit syilx and local government authority,” explained syilx Nation member qʷəqʷim̓cxn Tessa Terbasket — one of main leads on the leadership table’s co-ordination team and watershed responsibility planning process. The current system “weakens” coordinated action and “undermines watershed health,” she said, highlighting that short-term and “uncertain” funding “erodes continuity” and the collaborative progress. “Water challenges are not just technical — they stem from policy and knowledge gaps that fail to uphold syilx and local government principles or support community-led stewardship,” she said. “A limited understanding of both syilx water knowledge and Western science creates a disconnect that prevents us from fully acting on our shared responsibilities for siwɬkʷ (water).” Member concerns about “diverse ecological pressures from human activity” on regional watersheds led to the development of the ecosystems working group, Terbasket said. “Across the region, the health of headwaters and source water, snowpack, springs, wetlands, creeks, rivers and lakes is declining due to land use changes, pollution, and cumulative and climate change impacts,” she said. The purpose, then, for the government working group is to propose and develop shared policy priorities and decision-making tools “grounded in both syilx and local government principles,” Louie said. As for the ecosystems working group, their job will be to set priorities for watersheds, identify place-based indicators — such as the health of keystone syilx species — to measure success. tmixʷ (All living things) and siwɬkʷ (water) indicators consist of keystone syilx species, such as stunx (beaver), c̓ayʼx̌aʔ (crayfish), ntityix (chinook spring salmon) and mulx (cottonwood). “These species, the water, were all here before the people-to-be came to this world,” said Terbasket. “This isn’t the be-all-end-all list. But this is a list to start with that the working groups can further explore with knowledge holders and experts.” Louie added that these indicators will “help guide us to what success looks like in the future.” “To indicate where we’re starting to see changes, the positive impacts that we want,” he said. The group will also develop projects that “build resilience, from the headwaters down to our lakes and rivers,” he said. Priority areas listed and emphasized for the ecosystem working group included fish habitat restoration; re-establishing salmon spawning tributaries; monitoring water quality; source water protection; changes to forest practices to include water and food systems; and more. Members of the of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table outline priority areas they wish to see addressed by the group’s two new working groups, during a meeting in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens As for the governance working group, highlighted priority areas called for a hybrid and collaborative governance structure; solutions for remediation in forestry and mining; policies around ensuring water compliance with forestry and mining; and more. The two working groups will each consist of at least eight leaders from the table, who will be supported by experts, Elders and knowledge keepers. They will then report their developments to the greater table at each meeting. Between now and their next gathering in February, the two working groups identified action items they wish to address: one is strengthening their communication strategy — internally and for the public — to be more clear about who they are and what their goals are. The other is to identify at least two waterways across the Okanagan-Similkameen watersheds that are in crucial need of restoration, and what immediate steps need to be taken to heal the water, which would help establish a baseline for similar restoration work in the future. “We’ve been talking a lot about issues. Now, it is time to get to work,” Louie said. suiki?st Pauline Terbasket, the executive director of the Okanagan Nation Alliance, said that everyone in the room has a shared responsibility to take care of the regional waters for future generations. “Access to clean water, access for our children to know that they can drink clean, safe water,” she said. “And it is stewarded in a way for all of us.” A ‘sense of urgency’ suiki?st Pauline Terbasket, the executive director of the Okanagan Nation Alliance, participates in discussions during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands at the Lower Similkameen Indian Band (LSIB) office on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens With the leadership table meeting only a handful of times every year, the pressure to act now and put ideas into motion is mounting, with the October 2026 municipal elections looming. Those elections affect both municipal and regional district electoral areas, and could change the face of the leadership table and who is involved. “We must work together to secure long-term funding and institutional stability that outlasts elections, staffing and shifting management,” said Louie. “There’s a sense of urgency.” Leaders were asked to share with the room what regional watershed success looks like 250 years into the future. “If the salmon are ok — our salmon relatives, the salmon nation — then we’ll be ok,” said y̓ilmixʷm (Chief) ki law na Clarence Louie of Osoyoos Indian Band. Many said they wish for more clean drinking water across the board, and for future generations to enjoy the water, as they had when they were younger. Others called for sustainable farming practices, changes to mining and forestry practices, and both water laws and protocols that would govern policies that protect water quality and watersheds. y̓il̓mixʷm (Chief) sil-teekin Greg Gabriel of the Penticton Indian Band participates in discussions during a meeting of the Okanagan Similkameen Collaborative Leadership Table in smǝlqmíx and syilx homelands at the Lower Similkameen Indian Band (LSIB) office on Nov. 21. Photo by Aaron Hemens “We need to build something that’s going to be consistent with any change in government, where the message is going to be the same,” said y̓il̓mixʷm (Chief) sil-teekin Greg Gabriel of the Penticton Indian Band. “Whoever replaces me — whoever replaces you — the message will continue on,” he added. “Hopefully we’ll have committed and strong leadership to make sure this work continues. That’s what I’m looking for — not in 250 years.”

Wednesday, 4 Mar 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma