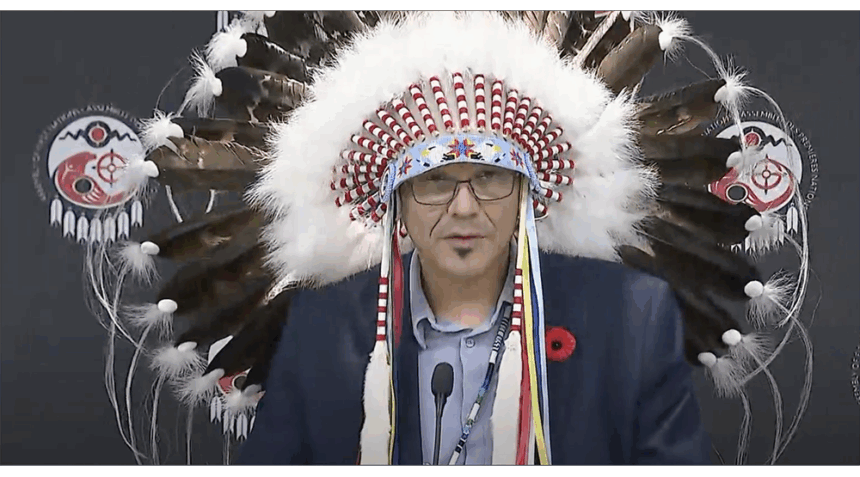

Mikisew Cree First Nation Chief Billy-Joe Tuccaro. (Sreenshot). By John Wirth, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter (ANNews) – Treaty 8 Chiefs from Cree, Beaver, Fort Chip Métis, and Chipewyan First Nations communities are gearing up to defend their people against continued damages from the waste “water” produced by tar sands developers. A collective statement declares their opposition that, “‘Treat and release’ remains of critical concern to all First Nations across Treaty 8 territory, especially those living downstream who experience the daily impacts of industrial development.” For decades now, these people have been living with the cost of our economy as crude oil and methane gas extraction remains a major source of Canada’s GDP. Grand Chief Trevor Mercredi (Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta) notes that, “When it comes to the health of our people, we’re being ignored. development takes precedent over our people’s health.” The land upon which the Treaty 8 peoples depend has been degraded, a direct violation of their treaty right to pursue their traditional vocations: fishing, hunting, and trapping. The animals they have stewarded have never seen an ecological tragedy on this scale. Climate change outpaces everyone’s ability to cope, we cannot drink oil or eat money. As National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak (Assembly of First Nations) stresses, this is a Canadian issue: “I know this country wants to talk about development, but what about the health of Canadians? And that includes First Nations and that includes all of your children, especially when it comes to water.” AFN Chief Nepinak adds, “Water is life and we know that it’s not merely a resource or a commodity to be traded or consumed. It is a gift from the creator flowing through the veins of this land and connecting all of us as living beings.” Today, the issue that cannot be ignored is that the waste liquid is slowly breaching its containment, a fact acknowledged by the industry. Without treatment, this toxic water follows its natural path through the groundwater and into the Athabasca River. In a conservative estimate, this risk directly affects communities in the Wood Buffalo region and over 150,000 people. The effects are disproportionately felt by the Indigenous population. Chief Billy-Joe Tuccaro (Mikisew Cree First Nation) states plainly that, “I am here today to tell Canada, tell Canadians that our people are facing a cancer crisis” While Indigenous communities and the Wood Buffalo Regional Municipality cooperate on water treatment, the process itself creates an unavoidable risk. To neutralize bacteria, chlorine must be added, which then mixes with dissolved organic carbons in the source water, producing cancer-causing by-products (Trihalomethanes). Communities have struggled with national boil water advisories even with advanced infrastructure, but the larger, unseen threat is the heavy metals and carcinogens in the source water—which boiling does not remove. So, they are released into the air they breathe through water vapour. The Scale of the Liability The tailings ponds contain over 1.3 billion cubic meters of fluids (or 1.3 trillion liters). But these numbers are abstract and hard to visualise—like the wealth of a billionaire. If you were to make a square reservoir around the downtown core of Calgary 5 square kilometers, the fluid would be approximately 260 meters deep – completely submerging the 191-meter-tall Calgary Tower with over 60 meters of fluid above it. The water used for every single tap, shower, and sprinkler in Calgary and Edmonton combined for over six whole years is equivalent to the volume of liquid the industry is planning to treat and release. The current cutting-edge technology already produces byproducts that are hard to remove and contribute to the significant rise in rare cancers in downstream communities. Can the companies be trusted to safely fix this vast, growing volume? Chief Tuccaro leaves no doubt on the uncertain nature of the solution: “The technology for treating these oil tailings is unproven and cannot guarantee that the water would be safe for my people to drink” He adds a powerful contrast, “If the water isn’t able to be treated and reused in the mines and for development, why is it good enough for us to drink? We’re tired of being the guinea pigs of Canada.” The conflict The core issue is that the proposed “treat and release” regulation seeks to legalize the discharge of this massive, toxic volume. Grand Chief Mercredi summarizes the environmental principle: “There has to be a better solution than dumping extremely toxic tailing ponds into a lake, a river that is diminishing in size each and every year.” Chief Tuccaro frames the choice uncomfortably clearly: “We are standing here today to call on these governments to care about the health of our people as much as they care about the health of fish and to take treat and release off the table.” He laments: “For what? Because people choose wealth over our health, profits over people.” The ponds are allowed to exist because of a loophole: current regulations prohibit release. The law that keeps the fluid in the ponds is Subsection 36(3) of the federal Fisheries Act, which states that no person shall deposit a deleterious substance in any place where it “may enter” water frequented by fish, even indirectly through groundwater seepage or surface runoff. Extraction companies had long maintained their stance of indefinite containment for tailings ponds. They were incentivized to do so, as the minuscule annual fines from the provincial regulator (AER) amounted to little more than a small business cost, offering no real incentive for change.

Thursday, 5 Mar 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma