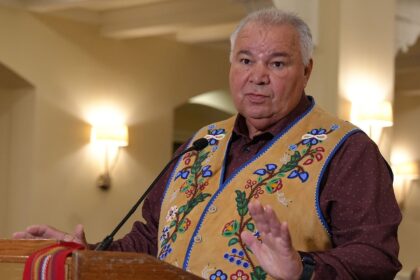

Thirty-three years is a long time in any domain, but in politics, it’s an eternity. When Ghislain Picard became regional chief of the Assembly of First Nations Quebec and Labrador (AFNQL) in 1992, Brian Mulroney was prime minister. The AFNQL was less than a decade old, the Siege at Kanesatake (Oka Crisis) was a recent and traumatic memory and the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples had just been struck. The Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee and the Inuit of Nunavik were working together in a series of protests that would defeat Hydro Quebec’s plan for the Great Whale Hydroelectric Development, sometimes called James Bay II. “In 1992, I would probably have been the last to think that I would be still helming the AFNQL 33 years later,” said Picard in a Face to Face interview—our first in French—with APTN’s Kim Sullivan. “Because I hadn’t thought about it as a career. Rather, it was a mission with a beginning and an end.” Born in the Innu community of Pessamit on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence River, Picard was raised speaking Innu-aimun at home and learned French at school. Though he was shy, he said he absorbed the talent of assertion from the greater community. “Obviously, as a minority, we tend to be more assertive, which I still notice to this day, several decades later,” said Picard. Ghislain Picard at the Assembly of First Nations gathering in Ottawa in December 2024. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN. Quiet assertion became a signature for Picard’s years as regional chief. Having grown up against the backdrop of the fight over Quebec’s first wave of hydroelectric development in the Cree Nation east of James Bay, he said he’s always understood Indigenous leadership as based on the need for assertion of territory, of title, of history, and of culture. But even that, he pointed out, “confronted people with choices that weren’t always clear cut.” To lead ten First Nations across a territory roughly three times the size of France, Picard said he focused on listening to and understanding people’s specific needs and opinions, and the contrasts between them. But he’s quick to dismiss the notion that answering to 43 chiefs across Quebec was an onerous task, framing it instead as an immense privilege. After all, he said, he’s inspired by challenges. “Where things got interesting is attempting to unite these diverse people into a cohesive whole. Diversity is our strength, and that’s what I saw every time the chiefs came together,” he said. “My role is determining the common thread, bringing it to the table and fostering discussion.” Open dialogue was a pillar of Picard’s leadership of the AFNQL, grounded in his conviction that the ten geographically disparate First Nations are best served when everyone has an understanding of one another’s needs and priorities. “I’ve always found that our communities had been somewhat in the background and finding it difficult to express our opinions,” he explained, “which I believe was the result of colonization. That was by design. We had to relearn how to listen, talk and form an opinion on issues that were part of our daily lives. I think that this shaped, in some way, who I became as regional chief.” After every election, he recalled checking in with himself to assess his health to continue, and his passion for the role. It took 11 elections, but this was the year he decided he would bow out while still on top. He had the energy and could have continued, but he felt the time was right, and he doesn’t have any regrets. “I didn’t hit a wall very often,” he said, “And for that, I tip my hat to the chiefs I worked with over the years. Both those who are here today, and those who’ve been there since 1992. That’s what informed the decisions I had to make.” But he said his work isn’t finished. Earlier this month he was in New York with a delegation of First Nations from Quebec calling for the provincial government to abide by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. This coming fall, he will teach a course at Concordia University in Montreal. Picard, second from left, with chiefs in Quebec at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in April. Photo: Karyn Pugliese/APTN. Picard said he hopes to find more time for his daughters and grandchildren, with whom he is very close. And though his social media profile has revealed he’s a prolific runner and cyclist, he says he hopes the distance from politics will allow him to get into even better shape—possibly enough to run his first marathon. But Ghislain Picard acknowledged he won’t ever be very far from politics. “We have no choice but to pay attention to the political environment in general,” he said, “which we do not control, or do not control as much as we would like.” He recalled a woman once asking him in Innu, “Ghislain, when are we going to get to where we want to be?” It’s a question he feels everyone must ask themselves in order to take stock of what they’ve accomplished and what they have yet to approach. “Self-determination is a goal that we all share,” he said, “And you can have different opinions on how to get there. But at the same time, I think everybody is really focusing on the goal. It’s a goal that I don’t think comes off the radar. And that brings me back to that question. “What I’ve noticed, and this is why I want to stay active beyond my decision to leave, is that there’s still a long way to go.” Continue Reading

Still a long way to go: Ghislain Picard reflects on 33 years of leading the AFN in Quebec

Leave a Comment