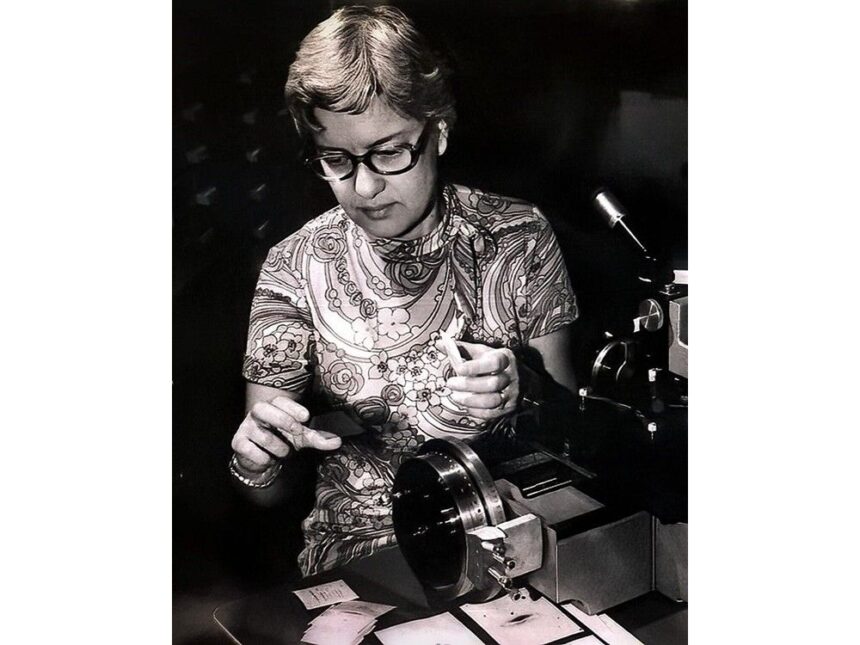

A new observatory with one of the most powerful cameras in the world has been named after female astronomy pioneer Vera C. RubinPublished Jul 02, 2025Last updated 15 hours ago7 minute readVera Rubin measuring spectra in 1974 at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C. Wikipedia Commons/NOIRLab/NSF/AUArticle contentNamed for a pioneering woman astronomer, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory has recently produced its first images.THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY.Subscribe now to access this story and more:Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsSUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES.Subscribe or sign in to your account to continue your reading experience.Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsRegister to unlock more articles.Create an account or sign in to continue your reading experience.Access additional stories every monthShare your thoughts and join the conversation in our commenting communityGet email updates from your favourite authorsSign In or Create an AccountorArticle contentThe Vera C. Rubin Observatory (VRO) is a newly-constructed astronomy and astrophysics facility located atop the Cerro Pachon mountain in northern Chile.Article contentArticle contentThe observatory is named in honour of Dr. Vera C. Rubin (1928-2016 ), an American female astronomer whose work provided the first clear evidence for the existence of dark matter — the enigmatic and invisible (thus “dark”) matter that astronomers believe constitutes more than 80 per cent of all matter in the modern universe.Article contentArticle contentThe VRO is a project jointly funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science. The observatory is equipped with a 8.4-metre Simonyi Survey Telescope, and the world’s largest — 3,200 megapixel — digital camera.Article content“We have peered into a new world and have seen that it is more mysterious and more complex than we had imagined.” – Vera C. Rubin, astronomerArticle contentWhat will the VRO do?Article contentDesigned to survey the entire Southern hemisphere sky, the VRO’s telescope and digital camera will track and image everything from asteroids to supernovae explosions to the movement of the most distant galaxies. It will also, astronomers hope, assist in solving the mystery of dark matter and dark energy.Article content This pair of images showcases the same region of sky as simulated by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (left, processed by the Legacy Survey of Space and Time Dark Energy Science Collaboration) and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (right, processed by the Roman High-Latitude Imaging Survey Project Infrastructure Team). Roman will capture deeper and sharper images from space, while Rubin will observe a broader region of the sky from the ground. Because it has to peer through Earth’s atmosphere, Rubin’s images won’t always be sharp enough to distinguish multiple, close sources as separate objects. They’ll appear to blur together, which limits the science researchers can do using the images. But by comparing Rubin and Roman images of the same patch of sky, scientists can explore how to “deblend” objects and implement the adjustments across Rubin’s broader observations. J. Chiang (SLAC), C. Hirata (OSUArticle contentEach night, the VRO camera takes more than 1,000 images of the Southern Hemisphere night sky, covering the entire sky every three to four hours. Its “first-look” images, released to the public on June 23, are the most detailed photos of space taken to date.Article contentArticle contentIn just the first 10 hours of its operation, and focusing on just a very small portion of the visible night sky, the VRO camera imaged more than 10 million never-before-seen galaxies in and beyond the Virgo Cluster in the constellation of Virgo – the Maiden, incredibly detailed images of the gas and dust that make up the Trifid and Lagoon nebulas, and more than 2,000 previously undiscovered asteroids.Article contentArticle contentOver the next 10 years, the VRO is expected to image over 20 billion galaxies, more than 17 billion stars in our Milky Way Galaxy, 10 million supernovae, and millions of smaller objects in the solar system. It is estimated that the data collected by the VRO by the end of its 10-year mission will amount to more than 500 petabytes, enough to fill half a million 4K-HUD Blu-ray discs.Article contentThe collected datasets will be distributed to three data centres around the globe in order to ensure redundancy, so that the datasets are not lost by accident.Article content The Vera C. Rubin Observatory telescope mount assembly. Rubin Obs/NSF/AURAArticle contentOnce it becomes fully operational later this year, the VRO will view and image more of the universe than all previous telescopes combined, and will revolutionize what we know about the universe in which we live.Article contentIf you would like a zoomable view of the VRO’s “first look” images, go to rubinobservatory.org, and click on any one of the four sections.Article contentWho was Vera C. Rubin?Article contentAfter earning a bachelor’s degree in astronomy from Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, USA in 1948, Vera C. Rubin attempted to enroll in the astronomy program at Princeton University, in Princeton, New Jersey, but was rejected due to her gender.Article contentAstronomy, and indeed most sciences, was, at that time, considered to be the exclusive domain of men. Incidentally, Princeton University maintained its policy of gender discrimination against women in its astronomy program until 1975.Article contentArticle contentUndeterred, Vera applied to and was accepted by Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where most of her degree course work was within the physics program. At Cornell, she studied galactic dynamics and the motion of galaxies. She graduated from Cornell University with a Master’s degree in astronomy in 1951, before going on to Georgetown University in Washington, DC, USA, where she received her Ph.D in astronomy in 1954.Article content Vera Rubin at Kitt Peak National Observatory in 1963 operating the observatory’s No.1. 36-inch telescope. Kent Ford’s Image tube spectrograph is attached to the telescope. With Ford, she continued using the Kitt Peak 2.1-m, accumulating over 60 galaxy rotation curves over the following years. Flat rotation curves were directly visible from the spectra: these data provided compelling observational evidence for a new kind of matter in the Universe, “dark matter”. Vera Rubin continued observing at Kitt Peak and Cerro Tololo throughout her long career. KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURAArticle contentOver the next 10 years, Vera held a number of short-term academic positions in the DC area. From 1955 to 1965, she worked at Georgetown University as a research associate astronomer, a lecturer, and, finally, as an assistant professor of astronomy.Article contentDuring her time at Georgetown University, Vera made her first observations of the rotation of galaxies, using the MacDonald Observatory’s 2.08-meter telescope.Article contentArticle contentIn 1965, she accepted a staff position at the Carnegie Institution of Washington (later the Carnegie Institute of Science) in Washington, DC, where she met the man who would become her long-time collaborator, the American astronomer Kent Ford (1931-2023).Article contentThat same year, she applied to become the first female astronomer to be permitted to observe at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego, California, USA. Although reluctantly granted permission, she was told, “Your time in the observatory is limited, because we don’t have a women’s bathroom.” There is an amusing anecdote that says that Vera pasted a paper skirt on the male stick figure on the bathroom door, and proceeded to use it, claiming that the observatory now had a women’s bathroom.Article contentWhat did Rubin discover?Article contentWhile working at the Carnegie institution, Vera and Kent closely observed the stellar spectra of stars orbiting the center of the Andromeda Galaxy in order to determine their velocities; what is referred to as a “galactic rotation curve” — in other words, how fast stars rotate around galactic centres.Article contentHer studies demonstrated that the stars in the outer spirals of the Andromeda Galaxy were orbiting at the same speed as the stars at the galaxy’s centre, and, further, that the stars in the outer galactic spirals were orbiting so fast that they should have flown apart.Article contentTo Vera, this implied that the mass of all the visible stars in the Andromeda Galaxy wasn’t sufficient enough to hold the galaxy together, thereby suggesting that there had to be an extraordinary amount of mass missing from the galaxy.Article contentSubsequent studies of numerous other spiral galaxies discovered additional unexplained rotation curves in those galaxies as well. Ultimately, Vera’s decades of observations of galactic rotation curves in spiral galaxies would be cited as evidence that spiral galaxies are surrounded by dark matter haloes, and that such galaxies must contain at least five to 10 times more mass than can be directly observed, based on the light emitted by ordinary matter.Article contentArticle contentHer observations supported the theory of the existence of dark matter, initially proposed by Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky (1898-1974) in the 1930s; as such, she is considered “the queen of dark matter”. Unfortunately, Vera C. Rubin did not receive a Nobel Prize for her work.Article content An aerial view of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory on Cerro Pachón in the Chilean Andes. Rubin Obs./AURA/NSF/B. SlivkaArticle contentSupporter of women in scienceArticle contentPerhaps more important than her many awards for her numerous contributions to the field of astronomy, Vera C. Rubin is remembered for her lifelong advocacy for the inclusion and greater recognition of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).Article contentVera was a strong mentor to many young female scientists, encouraging and supporting them, as well as her male students, regardless of their age, gender, or nationality. Throughout her life, she approached numerous scientific journals, professional societies, and educational institutes, urging them to provide more opportunities for women scientists.Article contentArticle contentThroughout her professional life, Vera fought against sexism and gender disparity. Unfortunately, as she discovered, women’s participation and accomplishments in the sciences have been under-reported, under-recognized, and under-honoured throughout most of history. While the STEM fields have come a long way with respect to women’s inclusion since Vera’s day, there is still much room for improvement.Article contentIf you would like to know more about the STEM initiative, go to en.wikipdeia.org/wiki/Women_in-STEM. If you would like to learn more about the remarkable woman Vera C. Rubin, go to en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_Rubin, and, finally, if you want to learn more about the Vera C. Rubin Observatory itself, go to wired.com/story/opening-of-the-vera-rubin-observatory/.Article contentArticle contentArticle contentThis week’s skyArticle contentMercury (magnitude -0.2, in Cancer – the Crab) is not observable this coming week, as it starts the week no higher than three degrees (0 degrees by July 13) above the western horizon at dusk.Article contentVenus (mag. -4.1, in Taurus – the Bull) rises in the east around 2:50 a.m. ADT, reaching 21 degrees (22 degrees by July 13) above the eastern horizon before fading from view into the brightening dawn by about 5 a.m. ADT.Article contentMars (mag. +1.5, in Leo – the Lion) is visible 14 degrees (12 degrees by July 13) above the western horizon around 10:10 p.m. ADT, before sinking towards the horizon and setting around 11:40 p.m. ADT.Article contentJupiter (mag. -1.9, in Gemini – the Twins) is not observable this coming week, as it is no higher than one degree (five degrees by July 13) above the eastern horizon at dawn.Article contentSaturn (mag. +1.0, in Pisces), rises in the east around 12:20 a.m. ADT, reaching 37 degrees (39 degrees by July 13) above the southeast horizon before fading from view with the brightening dawn by about 4:35 a.m. ADT. On July 13, Saturn enters retrograde motion; i.e., it reverses its apparent motion, moving in the opposite direction across the night sky.Article contentArticle contentUranus (mag. +5.8, in Taurus) is not observable this coming week, as it is no higher than 11 degrees (17 degrees by July 13) above the eastern horizon at dawn.Article contentNeptune (mag. +7.9, in Pisces), rises around 12:20 a.m. ADT, reaching 32 degrees (36 degrees by July 13) above the southeast horizon before fading from view in the pre-dawn sky by about 3:45 a.m. ADT.Article contentThe full moon on July 10 is sometimes referred to as the “Buck Moon,” as this is typically the time of the year when the antlers of male deer reach their peak growth after having been shed earlier in the spring. Interestingly, deer antlers can grow as much as 0.6 cm (one-quarter inch) per day during their regrowth period.Article contentUntil next week, clear skies.Article contentEvents: July 10 – Full “Buck Moon”Article content

ATLANTIC SKIES: What will the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory reveal about the universe?