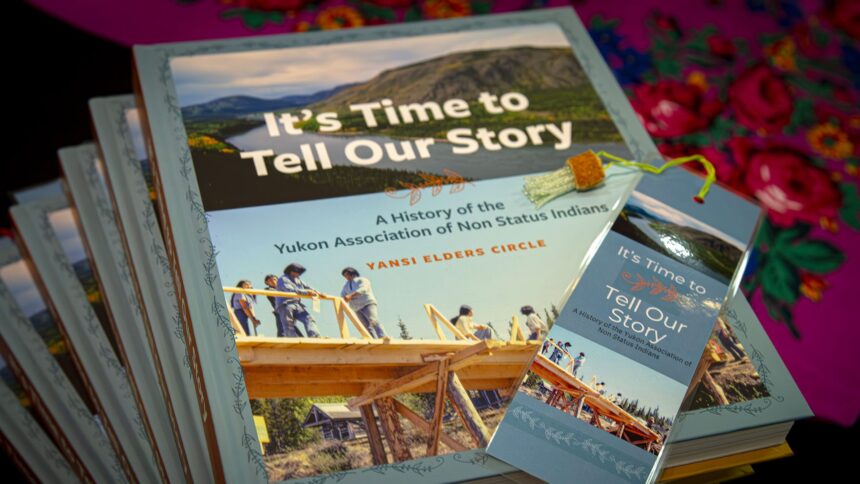

A new book is celebrating the history and achievements of a former First Nations organization in the Yukon that helped non-status people in the territory fight for equality. The Whitehorse Aboriginal Women’s Circle (WAWC) held a launch event on Sept. 29 for the release of It’s Time to Tell Our Story: A History of the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians. The Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians, or YANSI, was founded to advocate for First Nations people who had lost their Indian Status through discriminatory sections of Canada’s Indian Act. “Basically, it was about equality. We were kind of on the bottom rung of the ladder. So, we fought to become equal. We wanted to participate equally in work and education, all those things,” said former YANSI president and Kwanlin Dün First Nation citizen Bill Webber. Webber, who is a member of the YANSI Elders’ Circle which helped guide the book project, said the group was instrumental in working with the territorial and federal governments and the private sector to improve the lives of non-status people. “It was a big challenge for us to fight the battles and negotiate and lobby for changes to improve it,” he said. Researcher and writer Janet MacDonald, a Liard First Nation member whose family was involved with YANSI, said around 50 interviews were conducted for the book, including with YANSI members – the bulk of which are now Elders – to bring the former organization’s history and stories to life. She said as Elders are getting older and passing on, it was important to have the work done now. “What kids today could understand through this book is that it just takes a grassroots group of people to work hard, with not a lot of money, but with the right mindset and to work together. You can accomplish anything,” she said. Living in the “in-between” Webber said YANSI existed at a time when non-status people experienced immense challenges. Under the Indian Act, a person’s status could be taken away for various reasons, such as a status woman marrying a non-status or non-Indigenous man, serving in the armed forces or even earning a university degree. The book mentions how the loss of Indian status had devastating repercussions and led to loss of rights, benefits and entitlements, such as healthcare, hunting rights, housing assistance and education funding, and, perhaps most importantly – loss of acknowledgment as a First Nations person. Webber said because his mother married a non-Indigenous man, she lost her Indian status, as did her children. “Your own people, Indigenous people, they’d look at you like somebody else. And the non-First Nations people would look at you as well,” he recalled of his early years growing up as non-status. Shirlee Frost, a Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation citizen, described her experience of growing up as non-status as living in the “in-between.” Frost, who was raised in the remote fly-in community of Old Crow in northern Yukon, said there was a “physical divide” during her childhood, as status and non-status people lived on opposite ends of the community, with government infrastructure like the RCMP building and the nursing station in the middle. She said she didn’t pick up on that divide until later life and her parents never talked about it. “They just lived it,” she said. The book launch event on Sept. 29. Photo: Mark Rutledge and Danica Rutledge YANSI’s achievements Webber said those experiences led to YANSI being formed in 1972, with locals established in Yukon communities. The organization helped members with issues like housing, justice and health care. Writer Lori Eastmure said archival records show how YANSI helped form the Native Construction Company, which brought together contractors and small business operators from all over the territory and allowed them to build bigger projects. She said YANSI also had a hand in creating the Yukon Trapper’s Association, which aimed to help First Nations trappers get a fair deal for their furs. The association still exists today. Eastmure also noted how records illustrate how YANSI took on the department of education, accusing it of neglecting First Nations’ students’ education by collecting data from its members. “I think we were all absolutely amazed, including YANSI, people very close to all of this, what was actually taken on, and the accomplishments of that, and then the long-term possibilities that came from that as well,” she said. Linda Johnson, another researcher and writer for the book, described how YANSI advocated for non-status people to have an equal seat at the table as the Yukon Native Brotherhood (YNB) during the land claims negotiation process with the federal government beginning in 1973. Johnson said neither YNB nor the government were eager to involve YANSI in negotiations at first. “This book really documents the non-status peoples’ fight for recognition, and it was a fight,” she said. “In 1973, the YNB went to Ottawa with their paper, Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow. YANSI protested that they had not been part of that. They had actually contributed to it, but they weren’t part of the trip to Ottawa.” Johnson said YANSI’s tenacity eventually helped it succeed in being included in negotiations. Around a decade after its formation, members of YANSI and YNB voted to amalgamate, forming the Council for Yukon Indians (CYI), the main organization that would go on to negotiate a Yukon land claims settlement. That work would later set the stage for the Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement in 1993, spearheading the territory as a leader of modern treaties in Canada. Eleven of the territory’s 14 First Nations are now self-governing. CYI would eventually become what is now the Council of Yukon First Nations. At the same time, Johnson said, many members of YANSI would go on to have political careers. Webber likewise noted how YANSI collaborated with the Yukon Indian Women’s Association and other organizations across the country to pressure the federal government to reinstate Indian status women who had lost their status through marriage. That advocacy work led to the creation of Bill C-31 which amended the Indian Act, reinstating women who lost their status through marriage while also allowing first-generation children of such marriages to gain status. Members of YANSI’s Elders’ Circle and researchers and writers who helped with the book. Photo: Mark Rutledge and Danica Rutledge YANSI’s legacy captured in book Webber said as the years have passed by, YANSI’s legacy isn’t at the forefront as it used to be, and he’s noticed many young people are unfamiliar with its work. He said that’s why it was important to have a book documenting its achievements. He said for now, the book will only be available for YANSI members and their families and at schools, libraries and universities. He said the hope is to eventually make it publicly available for anyone to purchase. “We want to make sure that the younger generations, and even the general public understand the wrongs that were done,” he said. Johnson said YANSI’s contributions to the Yukon’s history should never be forgotten. “It’s an amazing story. To see it all together in one book, I think most people forgot how much was accomplished. So, I think there’s a real legacy in this.” Continue Reading

Book celebrates former First Nations organization that fought for equality for non-status people in the Yukon

Leave a Comment