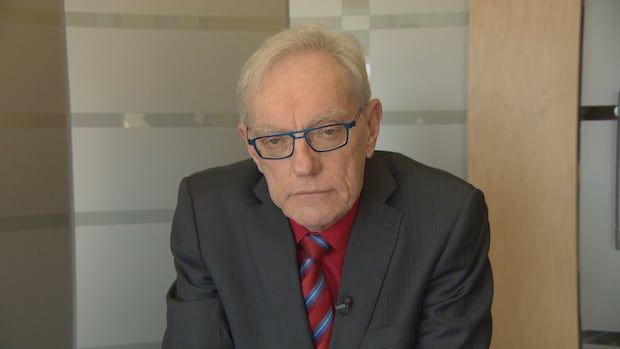

SaskatchewanThe College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan (CPSS) has declined the provincial government’s request to investigate the Dr. Goodenowe Restorative Health Centre in Moose Jaw.College says if the province wants Goodenowe centre investigated, that’s up to the Ministry of JusticeGeoff Leo · CBC News · Posted: Dec 04, 2025 11:53 AM EST | Last Updated: December 4Listen to this articleEstimated 5 minutesThe audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.Bryan Salte is the registrar with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan. (CBC)The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan (CPSS) has declined the provincial government’s request to investigate the Dr. Goodenowe Restorative Health Centre in Moose Jaw, saying CPSS doesn’t have the tools or authority to do so.The province made the appeal in a letter to the college on Tuesday, in response to a CBC investigation involving a client of the centre, Susie Silvestri.“The ministry is concerned about this individual and private business engaging in what appears to be the unauthorized practice of medicine,” wrote Tracey Smith, deputy minister of health.The centre’s founder, Dayan Goodenowe, says he has found a way to halt and reverse the symptoms of ALS — a degenerative disease that attacks the muscles. He has offered a three month live-in program where clients take a “systematic protocol” of his supplements, which he says will lead to “biochemical restoration.”In earlier statements to CBC, Goodenowe said he is not a medical doctor and his facility does not provide medical treatment.Dayan Goodenowe says his program can stop ALS symptoms from progressing and help patients restore their health. (CBC News)Goodenowe told CBC that every person who comes through his facility, “leaves that centre better than they came in, OK? And that’s just simply a fact.”Silvestri, a 70-year-old American suffering from ALS, put her North Carolina home up for sale so she could afford the $84,000 US bill and went to Moose Jaw last September. However, according to her own text messages, medical records and former Goodenowe employees, her condition deteriorated while at the centre. She died in an American hospital on Dec. 26, 2024.Susie’s situation is reminiscent of the stories shared by other Goodenowe clients in an earlier CBC story. Dayan Goodenowe, the man who runs the facility, has questioned those reports and filed a lawsuit against CBC claiming its coverage of his program is defamatory.Through his lawyer, Goodenowe has declined comment to CBC about Susie Silvestri’s story. However, he did provide a statement to Moose Jaw Today.”Any suggestion that [Susie Silvestri’s] health deteriorated or that she died under our care … or as a result of decisions made by my centre … is incorrect,” he told the online news site in a written statement.In December, Susie Silvestri was no longer able to eat and was begging for a feeding tube. (Former Goodenowe worker)College says noIn the health ministry’s letter, Smith wrote, “I am requesting CPSS to take all appropriate steps, including opening a formal investigation into the centre for any infringement” of provincial legislation.The Medical Professions Act, 1981, forbids non-doctors from treating or offering to treat disease for a fee. It also forbids a non-doctor from holding themselves out as a doctor.However, Bryan Salte, associate registrar and legal counsel with the college, says the act does not empower the college to investigate non-doctors allegedly practising medicine.“We have responded to government, advising it that The Medical Profession Act, 1981 does not provide the tools necessary to deal effectively with a business that practises medicine without a licence,” Salte wrote.He said the act does provide the college with tools to investigate licensed physicians. For example, the college has the power to obtain search orders and conduct investigative interviews. But, he said, the act does not empower the college to use those tools to investigate non-physicians.Furthermore, he said that under the current act, the maximum penalty for practising medicine without a licence is $5,000.“That is not likely to be a meaningful deterrent if the person practising medicine is making a significant income from that practice,” he said.Salte said he has written to his counterpart colleges across the country to learn how situations like this are handled in their respective provinces.He said in some jurisdictions, the law gives colleges the power to seek an injunction. In those provinces, “the College will seek a statutory injunction to prohibit the person from practising medicine rather than trying to prosecute the individual for the unlicensed practice of medicine.”He said the provinces taking this approach noted that “an injunction is quicker, cheaper and more effective than prosecuting a person for the unlicensed practice of medicine.”In other provinces, prosecuting people for practising medicine without a licence is done by the Ministry of Justice, Salte said.He said that’s an available path for the province.“If there is to be such a prosecution, it must proceed under The Summary Offences Procedure Act, 1990. That means that the prosecution occurs in provincial court,” Salte wrote.He said anyone has the ability to prosecute an offence under this act and “that includes the Government of Saskatchewan or the Department of Health.”Salte noted that the Ministry of Justice prosecutes provincial offenses routinely.ABOUT THE AUTHORGeoff Leo is a Michener Award nominated investigative journalist and a Canadian Screen Award winning documentary producer and director. He has been covering Saskatchewan stories since 2001. Email Geoff at geoff.leo@cbc.ca.

College of Physicians and Surgeons wont investigate Moose Jaw health centre because it lacks the authority