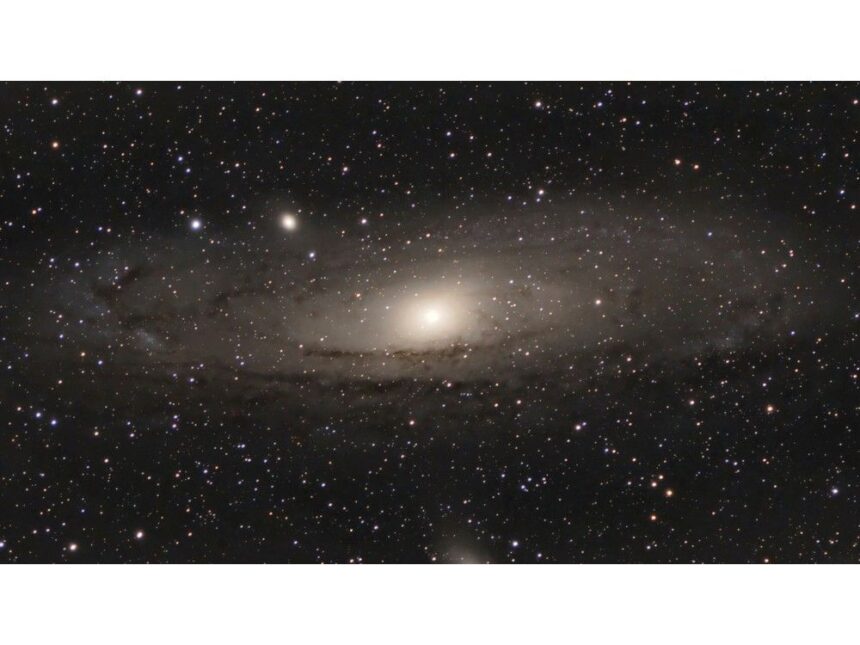

What used to be an expensive hobby requiring great expertise, astrophotography is now more affordable and easier with smart technologyAuthor of the article:By Gary Kean • The TelegramPublished Sep 23, 20259 minute readThe Andromeda Galaxy, the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way at a distance of 2.5 million light years, is a faint fuzzy patch in the night sky to the naked eye, but is a spectacular sight for astrophotographers, even newbies like Darren Hatt of Sunnyside NL, to focus in on. Photo by Darren HattArticle contentThere’s hardly a soul an Earth-bound soul who doesn’t enjoy gazing up at the stars in the night sky every now and then, but there’s much more out there than what the naked eye can observe. THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY.Subscribe now to access this story and more:Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsSUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES.Subscribe or sign in to your account to continue your reading experience.Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsRegister to unlock more articles.Create an account or sign in to continue your reading experience.Access additional stories every monthShare your thoughts and join the conversation in our commenting communityGet email updates from your favourite authorsSign In or Create an AccountorArticle contentThe accessibility of deeper space has long been the realm of astrophotographers with not only prerequisite experience and skill, but also the expensive equipment needed to find and create images of star clusters, nebulae, distant galaxies and the like. Article contentArticle contentArticle contentThat is changing quickly. Exploring the far reaches of the universe is now within a lot closer reach than it ever was. Article contentNot only that, but Newfoundland and Labrador — with its vast tracts of land far from light pollution — is one heck of a cool place to pursue the hobby. Article content Part of the Orion constellation, as viewed from Easter Island in the South Pacific, where its orientation looks upside down compared to the view from the Northern Hemisphere. Photo by Melanee WhitelockArticle contentFrom Down Under to up above Article contentMelanee Whitelock — who is originally from Australia but has called Robert’s Arm home for nearly five years now — says her passion for deep space was ignited when she was just a young girl. Article contentShe would venture out into the Outback, where there was little to no light pollution, and admire the tremendous views of the Milky Way and easy-to-find constellations like Orion or the Southern Cross as they stood out among the blanket of stars overhead. Article contentIn 1986, when she was 10, Whitelock was given a set of binoculars to get an even better view of Halley’s Comet as its roughly 76-year orbit around the sun swung close enough by Earth to be visible. Article contentArticle content“That changed everything for me,” Whitelock said in an interview with The Telegram. Article content Now living in Robert’s Arm, NL, Melanee Whitelock is an astrophotographer from Australia who is eager to get back into the hobby for the first time since moving to North America 11 years ago. Photo by Melanee WhitelockArticle contentArticle contentOld-school costs Article contentGetting into astrophotography years ago was no cheap venture. Article contentTo capture faint signals from celestial objects that are profoundly distant and then create high-quality images of them, a camera equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) sensor was essential. Article contentSuch a camera can cost thousands of dollars, and it certainly did when Whitelock began immersing herself in astrophotography. Article contentThree images she shared with The Telegram, including one of the Horsehead Nebula found within Orion’s Belt at a distance of 1,375 light-years from Earth, were taken with a camera that cost $25,000 around 14 years ago. Article contentThe Orion image was taken through a 20-inch Maksutov telescope in a custom-made observatory she was renting. Whitelock figures that the huge telescope probably cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Article contentEven a smaller one, such as 10-inch Dobsonian telescope, would cost in the vicinity of $5,000 around the time Whitelock was shooting the stars from Australia. Article content“Everything I’ve used has been old school, hand-wound to keep track of the stars, or incredibly expensive stuff,” said Whitelock. Article contentShe did work as a docent at the Perth Observatory in Bickley, Western Australia, but Whitelock has not peered through a big telescope since moving to North America from Australia 11 years ago Article content“The thing I miss is not having a big telescope.” Article content This image of the Horsehead Nebula, found in the Orion constellation, was created by astrophotographer Melanee Whitelock around 14 years ago when she lived in Australia. Photo by Melanee WhitelockArticle contentOld-school methods Article contentIn addition to the expensive gear, one must also acquire knowledge and skill to properly put the equipment to good use. Article contentWhitelock had to learn the processes involved in the old-school way, too, since there was no such thing as an online search for how-to guidance when she first began educating herself about the craft of celestial photography. Article contentArticle content“It was very hard for me to learn it all by myself before the Internet, because there’s nobody with you,” she said. Article contentIt’s easy to get lost in the physics of figuring out how to carefully stack three hours’ worth of 30-second exposures to produce a final image like the ones she created while living in Australia. Article contentEach deep space image is actually taken in black and white, and the photographer must use filters during the stacking process to bring out the vibrant colours hiding in the great beyond. Article content“You really don’t know what you’ve shot until you bring those images in, you stack them and flatten it to see what you have caught and how good your collimation has been,” she said, the latter term referring to the process of aligning the components of the device being used to ensure precision and focus of the final image quality. Article contentAn image she captured of the Andromeda galaxy, for instance, turned out a bit blurry because the photos she used were not optimally aligned.Article contentArticle content Using old-school equipment and processes can be challenging, as seen by this blurred composite image of the Andromeda Galaxy created by Melanee Whitelock, who believed smart telescope technology will make astrophotography more accessible to everyone. Photo by Melanee WhitelockArticle content ‘It’s going to blow my mind’ Article contentNow that she’s making her home in Newfoundland and Labrador, Whitelock is looking forward to a much easier and less expensive approach to doing astrophotography. Article contentTechnology has certainly made the hobby far more accessible to anyone with an interest in it. Article contentShe doesn’t have it in her possession yet, but Whitelock is eagerly awaiting the arrival of her new smart telescope. It features innovative technology that can do much of the work that once had to be done manually, including finding celestial objects and stacking the series of exposures to create the final image. Article contentThe real kicker is that smart telescopes cost a fraction of what traditional deep space photography equipment would. Article content“It’s going to blow my mind when it arrives,” said Whitelock, who has been spending her time getting acquainted with the stars visible from the Northern Hemisphere that she could not observe from Australia. Article contentThe orientation of the stars that can be seen from both hemispheres also takes some getting used to. The Orion constellation, which comes into view in the Northern Hemisphere during the fall and winter months, appears upside down when it can be seen in the Southern Hemisphere the rest of the year. Article content Originally from Ontario, Darren Hatt began taking night sky photos, like this one of the Milky Way over his hometown of Sunnyside, NL, and has advanced to creating images of celestial objects from far deeper in space. Photo by Darren HattArticle content‘Opens everything up’ Article contentDarren Hatt from Sunnyside, NL, knows all about the excitement that’s in store for Whitelock when she gets her new gadget. Article contentA professional photographer who moved to Newfoundland and Labrador from Ontario several years ago, Hatt makes his living doing mainly portrait photography. Article contentHe’s dabbled in the realm of shooting wide star fields in the night sky, usually the Milky Way, but had never explored deep space photography — mainly due to the prohibitive costs associated with it. Article contentThis summer, though, he purchased a Seestar S30, a small but mighty all-in-one smart telescope. It’s probably the best $650 he’s ever spent. Article contentArticle content“It packs all of the technology right into a tiny little kind of smart machine,” he explained. “Just that and a little tripod and a smartphone, and it opens everything up for you.” Article contentThere are other smart telescopes available that are even less expensive, and some that are pricier that might have additional bells and whistles. Article contentHatt chose the one he has because it had good reviews and seemed to be one that best met his purposes. Article contentJust as the night sky has been revealed in new ways for Hatt, this new technology unveils the cosmos for just about everyone, he said. Article content“When you compare it to what people would have had to spend to get into astrophotography proper, it’s really opened up to everyone now,” he said. Article content“I know $600 is still a lot of money to many people, but, comparatively, it’s a huge development to make the whole thing more accessible to everybody.” Article contentArticle content Astrophotography has become more accessible, thanks to smart telescopes like the Seestar S30 that Darren Hatt of Sunnyside, NL, uses to get images from deep space. Photo by Darren HattArticle content‘Let it do its thing’ Article contentJust weeks into learning the ins and outs of what he can do with this powerful little device, Hatt has posted some rather amazing captures from deep space on social media. Article contentThe images have been impressive enough for people to ask him how he does it, how long he’s been doing it and if he offers tutorials. Article contentHe’s accomplished all that from simply setting it up in the driveway of his home in Sunnyside, where the only light pollution of any concern on moonless nights comes from the refinery at Come By Chance, about five kilometres away. Article content“I could drive half an hour away and just get completely away in the darkness,” said Hatt. “But, for now, I’ll stay in my driveway and let it do its thing and maybe take a nap or go to bed and pick it up in the morning.” Article contentThe device takes care of all of the steps from tracking the target location in the sky, taking the images and then stacking them to produce the final version. Article content“It does all of that inside this little machine, so it saves so many steps,” said Hatt. “I was telling my wife I feel like a bit of a fraud because all these people are asking ‘what do you do, what’s your secret, do you do workshops,’ but it’s all just there, so it’s more accessible than it’s ever been before.” Article contentAs dramatic as some of his images have been, Hatt said he’s not about to incorporate them into his professional photography business. Article content“I don’t think the quality of this particular machine is enough to sell any large-format prints, but, if I can get a more impressive rig someday, then that would be something I’d consider for sure,” he said. Article content The Western Veil Nebula, also referred to as the Witch’s Broom Nebula, is the remnant of a supernova – the explosion resulting from the death of a massive star – an estimated 2,400 light years away and found in the Cygnus constellation. Photo by Darren HattArticle content‘Skies here are just amazing’ Article contentHatt is already eyeing the even more impressive versions of the technology, which can cost as much as $7,000. Article contentThe one Whitelock is awaiting the arrival of is a larger version of what Hatt has, which only adds to her excitement at getting back into astrophotography in this newfound way. Article contentArticle content“The skies here are just amazing — everything about Newfoundland is amazing,” she said. “We don’t have (good skies for viewing) all the time, but we have very friendly clouds and, when we do have it, my gosh, is it worth it.” Article contentShe does have plans to commercialize her love of astrophotography. She and her husband are planning to build an inn and an observatory in Robert’s Arm. Article contentWhitelock is still doing her research on the night sky as seen from Newfoundland and Labrador, as it will help determine the scale of what she plans to erect at the site. Article content“I’m going to build appropriately rather than go overboard,” she said. Article contentArticle contentWhitelock is considering making smaller smart telescopes available for rent to people who can log into them remotely. Article content“The software and the filters and all the things involved in (astrophotography) is very technical, but I feel these new little smart scopes take that away and you don’t need to worry about it anymore,” she said. Article content The Western Veil Nebula, also referred to as the Witch’s Broom Nebula, is the remnant of a supernova – the explosion resulting from the death of a massive star – an estimated 2,400 light years away and found in the Cygnus constellation. Photo by Darren HattArticle contentOutreach beyond the stars Article contentWhitelock hopes to spread her lifelong passion by stimulating more dialogue within the astrophotography community that already exists in the province and grow its numbers. Article contentShe and Hatt have already connected after she commented on a social media post he made about how he has found his new passion in astrophotography and shared some of his images. Talking to Hatt helped her figure out what smart telescope she would order. Article content“I don’t know him at all, but I was really so inspired by it,” she said of networking with Hatt. “I was so excited because I’ve spoken to a lot of people about it all since I’ve got here and I just haven’t found anyone that’s into it.” Article contentWhitelock would also love to bring the far reaches of the cosmos to young and old alike who may otherwise have believed this sort of activity was out of their world. Article content“I think it’s really important to bring this to the kids and to the big kids like me … We should all take a look,” she said. Article content The Triangulum Galaxy, also known as Messier 33, is a spiral galaxy 2.73 million light years from Earth and is found in the Triangulum constellation and not far from the Andromeda Galaxy. Photo by Darren HattArticle contentLearning astrophotography for free Article contentEven those who don’t have the resources to buy the equipment needed can still learn about astrophotography, noted Whitelock. Article contentBy logging in online, anyone can freely access deep space images taken by Hubble or the newer James Webb Space Telescope. People can also download stacks and learn how to process them to create images of celestial bodies. Article content“You can start getting astrophotography processing experience and recognizing deep space objects through the winter when we’re all stuck inside … Having access to these data sets is a lifelong dream for any space nerd,” said Whitelock. Article contentArticle contentIn fact, Whitelock has introduced the hobby to some people who have disabilities as a way to help them cope with their boredom. Article content“It may look scary to do, but it’s really easy,” she said. “The instructions are there on the website, kids can get involved in it, and it’s free.” Article contentGo online:Article contentIntro page to James Webb Space Telescope data processing: https://jwst-docs.stsci.edu/accessing-jwst-data#gsc.tab=0 Article contentArticle contentArticle contentArticle contentArticle content

Deep space photography more accessible than ever and NL is a great spot to do it