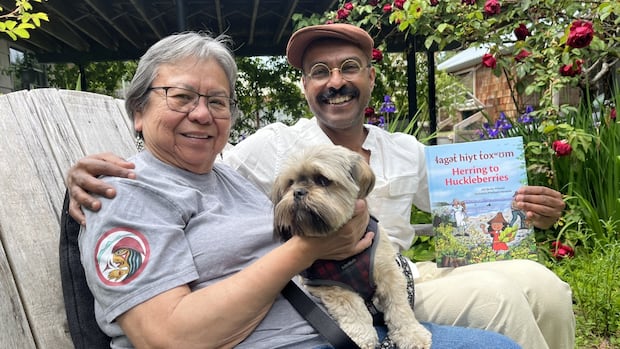

British Columbiaɬagət̓ hiyt t̓oxʷʊm Herring to Huckleberries by ošil (Betty Wilson) is written in both English and ʔayʔajuθəm, helping to teach the next generation of Tla’amin their traditional language.ɬagət̓ hiyt t̓oxʷʊm Herring to Huckleberries by ošil (Betty Wilson) is written in both English and ʔayʔajuθəmCourtney Dickson · CBC News · Posted: Sep 30, 2025 8:00 AM EDT | Last Updated: 33 minutes agoTla’amin elder and educator ošil (Betty Wilson) and artist Prashant Miranda have released a new book that aims to teach the next generation about Tla’amin language and culture. (Submitted by Prashant Miranda)When settlers colonized the southwest coast of what is now known as British Columbia, the Tla’amin Nation’s language ʔayʔajuθəm, or ayajuthem, was fragmented, the nation says. But before that, it had been passed down generationally. The nation says a writing system was not needed — the language was spoken, it was robust and it served the Tla’amin people well. That’s why people like Tla’amin elder and educator ošil (Betty Wilson) have spent years revitalizing and teaching ʔayʔajuθəm, to bring back something that was once so central to the Tla’amin Nation’s culture. Now, ošil and long-time friend and artist Prashant Miranda have released a children’s book, teaching the next generation about their culture, and their traditional language. ʔayʔajuθəm, pronounced eye-uh-joo-thum, is the traditional language of the northern-most Coast Salish peoples, including the Tla’amin Nation, the Homalco First Nation and the Klahoose First Nation. While a 2022 report from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council found that Indigenous language learning is on the rise, there were still only 3,370 fluent speakers throughout B.C., and 6,985 semi-speakers — a fraction of the First Nations population of about 180,085 at the time. Learning and speaking traditional language isn’t just good for culture — a study from the University of British Columbia found that when Indigenous people speak their languages, they also experience better health outcomes. “I think the country, or the world, is starting to recognize how important languages are for our own well-being as nations,” ošil said.Herring to Huckleberriesɬagət̓ hiyt t̓oxʷʊm Herring to Huckleberries, published by HighWater Press, tells the story of ošil and her grandparents as the seasons change and herring return to the waters in southwest B.C., marking an important time for the Tla’amin Nation as they gather food and connect with the land. On one page, the story is in ʔayʔajuθəm, while in the next, it’s translated to English. It all came to be while ošil was going through medical treatments, sitting in a waiting room with her laptop, writing down memories. “I’m always trying to think of different ways of promoting the language and having our people have multiple ways of hearing the language.”The story by ošil is accompanied by Prashant Miranda’s illustrations, which he created based on stories ošil shared with him. (Submitted by Prashant Miranda)When she showed Miranda, he knew she had to have the story published. “Over the last 10 years, I’ve just been hearing these incredible stories from ošil Betty Wilson, and it’s … led to this book,” he said. Miranda poured his own skills as an artist into bringing the book to life; his illustrations were born out of just three photographs of ošil and her grandparents that she shared with him. “I did a little watercolour of ošil as a kid with a little Coast Salish hat digging clams on the beach,” Miranda said. “The next day, Betty went, ‘That’s me as a kid!'” To ensure his images helped tell the story just right, he did a few rough drawings and asked her whether they were accurate to what she remembered, things like the fireplace in her grandparents’ home, and sleeping under the stars with her loved ones. “At first I was a little embarrassed, I went, oh, this couldn’t go public,” ošil said. “I’m kind of a private person.”ɬagət̓ hiyt t̓oxʷʊm Herring to Huckleberries, published by HighWater Press, is available for purchase now. (Submitted by Prashant Miranda)But since the book came out, she’s had to give up that private life because there’s been so much interest in her and her work, and in learning ʔayʔajuθəm. She’s been doing readings in schools, not only teaching parts of the language to young children, but also teaching them about their land and heritage. And while the book is targeted toward children, aged six to eight, ošil hopes the book becomes “everybody’s book.””The main reason I was doing this was for my community, for the three communities that used the language and other nearby communities,” she said. “This is only a beginning, a small part.”LISTEN | More on ɬagət̓ hiyt t̓oxʷʊm Herring to Huckleberries: North by Northwest16:59ošil (Betty Wilson) and Prashant Miranda on their new book, Herring to HuckleberriesT’la-amin elder ošil and artist Prashant Miranda reflect on bringing language revitalization to a young audience with their new children’s book Herring to Huckleberries, which ošil wrote both in English and ʔayʔajuθəm. ABOUT THE AUTHORCourtney Dickson is an award-winning journalist based in Vancouver, B.C.With files from North by Northwest and Santana Dreaver

Monday, 12 Jan 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma