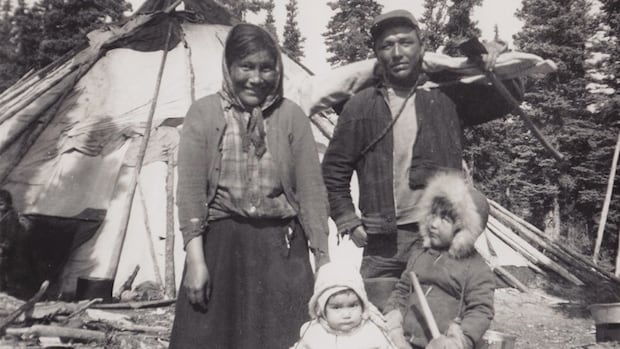

Before running water, electricity or roads connected their communities, Cree families lived off the land fetching water from nearby streams, heating log cabins with wood, and hunting for their food.More than 50 years after the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA), two Cree leaders — Bertie Wapachee and Gordon Blackned — reflect on what life was like before the landmark deal transformed Eeyou Istchee. As children in the early 1970s, they witnessed their communities weave their traditional ways of living into an era of modernization.‘It’s been a fast-moving world for the Cree ever since the JBNQA was signed. I hope the next 50 years, we will strengthen our language, protect our land and our identity,” said 74-year-old Gordon Blackned, who’s from the Cree Nation of Wemindji and now resides in Waskaganish, Que. The JBNQA was signed in 1975 between the Cree, Inuit, Quebec and federal governments. It was created after opposition to a major hydroelectric project in northern Quebec.Signing ceremony of the James Bay Settlement between the Quebec Government and the James Bay Cree on November, 1975 in Montreal, Que. (Southam Inc./Montreal Gazette)The deal recognized Indigenous land rights, provided self-governance and compensation.It became Canada’s first modern treaty, setting a model for future agreements.Blackned lived in the bush with his family and grandparents on their trapline until he was eight years old. They spent three seasons there each year, returning to Old Factory — now known as Wemindji — during the summer months, along with other members of the community.“During that time, most people when they returned from their traplines, they lived in tent frames, and wigwams,” he said.As a boy, his tasks included hauling buckets of water into the dwelling, carrying in the firewood his father had chopped, and hunting small game, such as ptarmigan, with his slingshot.A man carries water buckets by a river in Eastmain, Que, in the summer of 1973. (George Legrady/James Bay Photographic Archives)He remembers some of the first signs of European civilization, a time of confusion for not just him, but others too. ‘I remember here in Waskaganish, they started building houses in 1975 for community members. That was something that people were unfamiliar with,” said Blackned.Ever since the signing of the agreement, the Cree have built self-governance, economic development, health-care, education, justice, and land rights across all 10 Cree communities. Blackned believes life has become easier for the Cree, but after a lifelong career with the Cree School Board, he remains concerned about the loss of language and traditional skills among younger generations. “We must teach our young people about their history, their traditions, their values, and all of the survival skills their parents and grandparents have lived through,” said Blackned.Marlene Georgekish, a Cree girl takes her first steps on land in a walking-out ceremony in Wemindji, Que, in 1960. (Mary B. Georgekish/James Bay Photographic Archives)For many, that passing down of knowledge isn’t just about remembering the past — it’s about grounding the next generation in values that once shaped everyday life. Yet as times change and new influences emerge, that sense of grounding has become harder to hold onto.“Family life and in our camps, there was no violence, there’s not a lot of bad influence going on. But today we have access to everything,” said 55-year-old Bertie Wapachee from the Cree Nation of Nemaska. LISTEN | Gordon Blackned reflects on what changed after the signature of the JBNQA:Eyou Dipajimoon (Cree)19:45Gordon Blackned reflects on what changed after the signature of the JBNQAGordon Blackned grew up in Wemindji and remembers what life was like before the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was signed. He also ended up working at some of the Cree entities that were created under the agreement. He shared his thoughts with us.He said as a child, he dreaded leaving the calm, structured life of his family’s trapline to return to the Nemaska settlement where alcohol use was far more common.“The role of children, I would say, is learning the skills, the traditional skills and traditions and customs. That was pretty much our role,” said Wapachee.Independence and self-directed learning were core to that way of life. He recalls never being told to restock the wood supply — he simply did it on his own.’Nemaska City’ temporary settlement in the muskeg outskirts of Waskaganish, Que., around the 1970s. (George Legrady/James Bay Photographic Archives)Much of what he learned came from his grandmother, who prepared food from start to finish — skinning small game, butchering larger animals, and processing hides to make moccasins and mittens for the cold months. She would patiently show him how to complete smaller tasks.“I remember being taught how to make the mesh on the snowshoes and how to sew every little thing from my grandmother,” said Wapachee.“As you get older, there’s different levels of teachings passed on as rites of passage.”Those lessons included hunting big game such as moose, bear, and caribou, as well as trapping medium-sized animals like beaver.Wapachee was five years old when discussions about the JBNQA signing began, as Hydro-Québec and the Quebec government started building access roads for dam construction. At the time, he said he didn’t fully understand what was happening.Children in Chisasibi, Que, in the summer of 1973. (George Legrady/James Bay Photographic Archives)“I can remember being told that the plan was to flood our old community and start flooding the land further north,” Wapachee said.”I only heard about the damming and the destruction that was coming for the sake of generating power, electricity. I didn’t know anything about electricity, but as I grew older, I made my own connections, I guess.”Flooding in their territory forced the people of Nemaska to leave their homes and relocate elsewhere.LISTEN | Bertie Wapachee recalls how the JBNQA affected Nemaska people:Winschgaoug (Cree)20:46Bertie Wapachee recalls how the JBNQA affected Nemaska peopleAs we approach the 50th anniversary of the signature of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, we are looking back at what changed in our communities. We spoke with Bertie Wapachee, who grew up in Nemaska. He shared his thoughts on what life was like before and after the JBNQA.For Wapachee, that new world meant more cars, lights, and warmth in the first modern homes being built.“I remember our first few vehicles. Our family vehicles and driving down the highway and onto this brand new road,” he said.His grandparents’ main means of transportation had been on foot with snowshoes, dragging toboggans by their waists, paddling canoes, and later, using snowmobiles — until eventually, vehicles took over.A Mistissini Cree man with a young boy by a traditional toboggan (Chick Bidgood/James Bay Photographic Archives)“I remember seeing the building of what is now the Billy Diamond Highway, you know? Brand new pavement. I remember the access from the highway to our new site. Our new location, Nemaska,” said Wapachee.As the community rebuilt itself, Wapachee grew up witnessing the resilience and adaptability of his people. The generation before him had faced upheaval but worked tirelessly to ensure that future generations could thrive with dignity and purpose.“I think what our elders did back then is to minimize the impacts the best way they could and set us up for our future,” said Wapachee.A Cree woman prepares seal skin under teepee in Eastmain, Que, summer of 1973, as a child takes a peek at what she’s doing. (George Legrady/James Bay Photographic Archives)The late Billy Diamond, a former Cree Grand Chief and one of the JBNQA signatories, was Wapachee’s foster parent.Wapachee later became a leader himself, serving in several roles including chairperson for the Cree Board of Health and Social Services. “Every generation has to do it. We have to learn from that and minimize the impact. Into the future with all the development that we’re facing today. We have a big job still to do,” said Wapachee.For him, the lessons of the past are not just memories but responsibilities — a call to continue the work of his elders. As new challenges emerge across Eeyou Istchee, he believes the same spirit of determination must guide the generations to come.The Cree Nation of Chisasibi, home of the largest of the Cree communities, will host a gathering to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the JBNQA.“It’s going to be very important and I hope it’s going to be a hell of a good battle for the next 50 years to protect our territory even more.” Wapachee said.

Thursday, 25 Dec 2025

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma