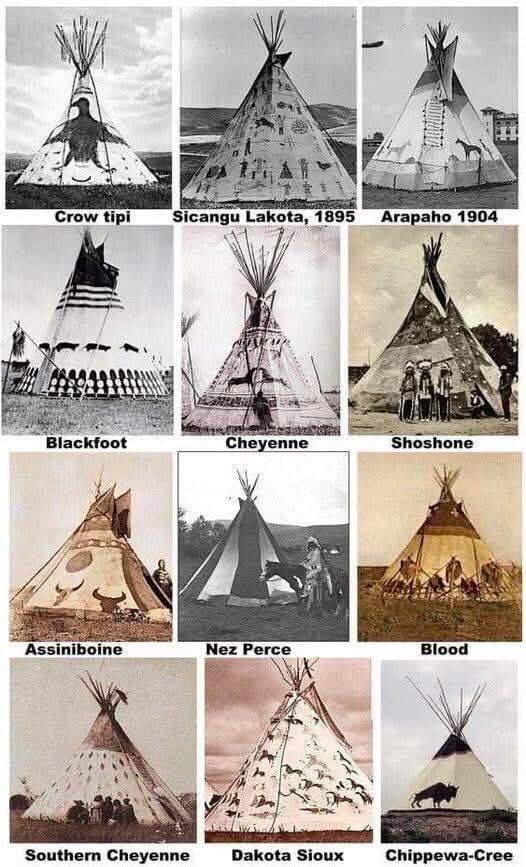

By the mid-1600s, the Ojibwa people living east of Lake Superior began their westward migration, and by the late 1770s, their settlements encircled the lake. One prominent settlement emerged along the Kaministikwia River. Historical records of Fort William during the early 1800s frequently note a Native encampment situated east of the fort’s palisade. A painting from 1805 depicts clusters of dome-shaped wigwams in the fort’s southeast corner, while later illustrations from the Hudson’s Bay Company era (post-1821) show conical tepees alongside wigwams.

These dwellings reflect the Ojibwa’s enduring ability to adapt to their environment, a tradition spanning thousands of years. Following seasonal cycles, Ojibwa family groups navigated the woodlands surrounding Lake Superior for fishing, hunting, gathering, and trading with other Native communities. With the arrival of European fur traders, many Ojibwa adjusted their practices to meet the demands of the fur trade, including trapping animals and maintaining prolonged contact with trading posts to provide pelts and other services.

In the western Lake Superior region, the Ojibwa—known also as the Saulteaux or Chippewa—were joined by the Cree to the north. Both tribes likely gathered at Fort William during the Rendezvous period, a time when Natives from surrounding areas exchanged furs, labor, and produce for goods at the fort’s Indian Shop. While many departed for their hunting grounds as summer ended, some remained to contribute to the fort’s winter activities.

During the North West Company (NWC) era, it is estimated that around 150 Ojibwa lived in the Kaministikwia district. Their names frequently appear in Fort William’s transaction records, suggesting that they formed a community adjacent to the fort. Though based near the fort, these groups continued seasonal journeys to harvest resources such as maple sugar, wild rice, rabbits, fish, and game, resulting in fluctuating population levels at Fort William.

Beyond their own endeavors, the Ojibwa played a vital role in supporting Fort William’s operations. Women worked in kitchens, canoe sheds, and on the farm, earning payment in trade goods. Men contributed through hunting, fishing, and providing labor or expertise required by the NWC. As producers, the Ojibwa were indispensable to the fort, supplying materials such as bark, spruce, and wattap for canoe-building, along with snowshoes, moccasins, skins, maple sugar, berries, wild rice, and fresh game.

The Ojibwa’s contributions and adaptability underscore their integral role in the region’s history and their enduring legacy as a community deeply connected to the land and its resources.

Native Encampment: Adapting and Thriving

Leave a Comment