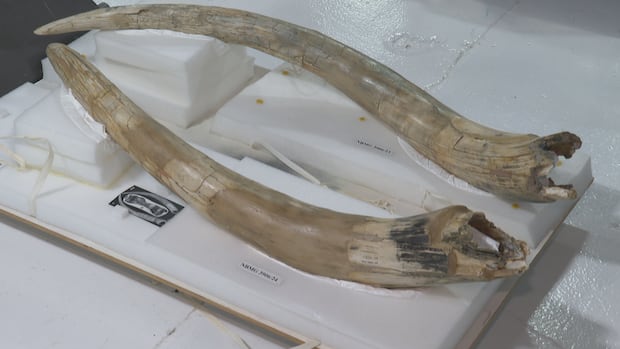

New BrunswickThe discovery of Marmaduke’s bones caused quite a stir in the small community 20 kilometres south of Moncton.Marmaduke was one of the biggest things around Hillsborough 75,000 years agoJordan Gill · CBC News · Posted: Nov 16, 2025 5:00 AM EST | Last Updated: 3 hours agoListen to this articleEstimated 5 minutesThe audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.The tusks of Marmaduke the Mastodon, who roamed the streets of Hillsborough, N.B., 75,000 years ago. (Ian Curran/CBC)July 2, 1936 was supposed to be just another day at work for C.R. Fancy, a civil engineer in Hillsborough, N.B.He and his crew were working on a small dam off a pond on his son-in-law Conrad Osman’s property.But work was halted when one of the men found a “peculiarly shaped rock.”On closer inspection, they realized that rock wasn’t rock — it was bone.“I knew then … that it was some kind of prehistoric monster,” Fancy told reporters for the Telegraph-Journal at the time. After 75,000 years underground, Marmaduke became an overnight sensation. (The Moncton Transcript)“I knew no animal in the province today has bones that big.”After 75,000 years, Marmaduke the Mastodon had been unearthed.Back in timeMarmaduke would have been alive during a transitional period in New Brunswick’s natural history.It was an inter-glacial period, when an ice sheet that had covered the province was slowly receding to the north.“This area wouldn’t have looked super different from the way that it looks right now,” said James Upham, a historian. Some of the many ribs of Marmaduke. (Ian Curran/CBC)“Except we have all these different kinds of critters in the woods including what’s officially called megafauna and including gigantic hairy elephants that are called mastodons.”Matt Stimson, the curator of geology and palaeontology department at the New Brunswick Museum said Marmaduke would’ve been between 15 and 18 years old at the time of his death —on the younger side — but still would’ve weighed about eight tons. And while he’s all bones, Marmaduke is in relatively good shape.“It’s one of the most complete juvenile skeletons in North America … even though it’s not 100 per cent complete,” said Stimson.While no eyewitnesses exist to confirm what led to Marmaduke’s demise, there are some clues in what he left behind.“This is coprolite and it’s fossilized poop from the mastodon,” Bailey Malay, curatorial assistant for the museum’s geology and paleontology department, said while holding what looked like a slightly misshapen cannon ball.A chunk of Marmaduke’s jaw, one of his femurs, and a sample of coprolite, better known as Mastodon poop. (Ian Curran/CBC)“We could find out what this mastodon was eating … there’s quite a bit of vegetation you can see in it.”In addition to dietary clues, the coprolite also provides some insight to Marmaduke’s untimely demise.“In this case we have this poop and a smaller poop, which indicates that unfortunately this animal probably starved to death,” said Malay.75,000 years laterThe discovery of Marmaduke’s bones in 1936 caused quite a stir in the small community 20km south of Moncton, according to Upham.“It was a fairly big deal,” said Upham.“If you happen to be digging around out here and you don’t necessarily know a whole lot about Ice Age megafauna, because it’s the 1930s, and you suddenly dug up this gigantic skull [it] would be an absolutely mind-blowing moment.”The dam where Marmaduke was rediscovered. (The Telegraph Journal)Newspapers at the time remarked on the completeness of the find and its condition, particularly the tusk, broken into three pieces, and jawbone, with the teeth surface “still smooth and shiny”Osman donated the remains to the New Brunswick Museum but first mandated that the bones be displayed at Hillsborough’s Memorial Hall for everyone there to see, which prompted some heightened security at the home.It turns out that this wasn’t an overreaction, as the Saint John Times Globe reported that a section of the tusk had already been stolen.“The guard is a precaution against souvenir hunters — the kind of souvenir hunters who cut pieces out of airplane wings, break chips off tombstones and, not long ago, tore the coat off Nelson Eddy, opera and movie star,” said the Times Globe.Conrad Osman, New Brunswick Museum director William MacIntosh and Gladys Osman posing with the remains of Marmaduke. (The Telegraph Journal)While it’s not confirmed exactly when the Hillsborough mastodon gained the name Marmaduke, the July 9 edition of the Saint John Times Globe includes one of the first mentions of the name.A tongue-in-cheek article, which suggests Marmaduke would have been a major attraction to stone-age big game hunters and speculates about Marmaduke’s attendance at the “sportsman’s exhibition at Boston,” said the name was one of convenience.After that the remains of Marmaduke were moved to the New Brunswick Museum, where he remains to this day.89 years laterMarmaduke now has a final resting place in the collections of the New Brunswick Museum on Lancaster Road in Saint John.The remains include impressively large tusks, femurs, hip bones and yes, the coprolite.Marmaduke doesn’t get taken out much. When the New Brunswick Museum was open, Marmaduke was represented by a model and reproductions of the bones.Matt Stimson, the curator of geology and palaeontology department at the New Brunswick Museum and Bailey Malay, curatorial assistant for the department, unpacking Marmaduke. (Ian Curran/CBC)But the real bones are wrapped up in layers of foam and plastic and locked away in large waterproof cabinets.While the bones are in good shape, they are still fragile, and need to be conserved for future generations.“Very often we don’t necessarily know what technology will be invented in 100 years from now that we can’t even conceive of,” said Stimson. “It’s our role … to make sure these important one-of-a-kind specimens are preserved long term for the next generation.”ABOUT THE AUTHORJordan Gill is a reporter based in Fredericton, New Brunswick.With files from Khalil Akhtar

Remembering Marmaduke, Hillsborough’s mastodon