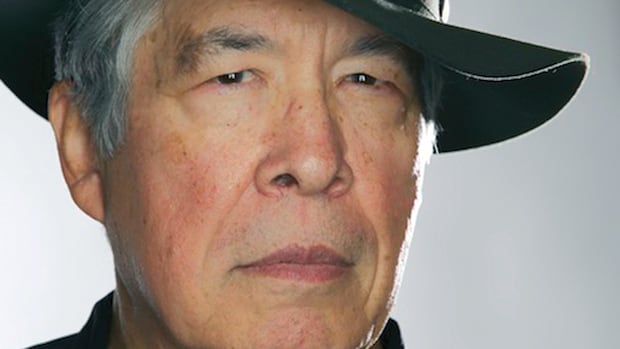

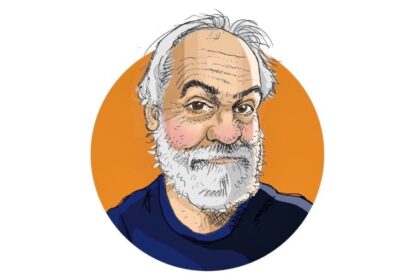

As It HappensAnishinaabe writer and scholar Niigaan Sinclair says Thomas King’s revelation that he’s not of Cherokee descent felt like “a gut punch.”Anishinaabe writer wonders why so many people with ‘dubious’ Indigenous ancestry take up so much spaceSheena Goodyear · CBC Radio · Posted: Nov 25, 2025 3:17 PM EST | Last Updated: 6 hours agoListen to this articleEstimated 7 minutesThe audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.Author Thomas King, 82, has revealed that he recently learned he is not of Cherokee descent, as he’d long believed and written about. (TrinaKoster Photography)LISTEN | Full interview with columnist and scholar Niigaan Sinclair:As It Happens6:35Thomas King revelation ‘a blemish on the entire Canadian literary industry,’ says Niigaan SinclairFor Anishinaabe writer and scholar Niigaan Sinclair, the revelation that author Thomas King is not Indigenous is a painful one. King is an award-winning Canadian-American author who earned his living writing about his complex relationship with Indigenous identity, most notably in his 2012 book The Inconvenient Indian. But on Monday, he revealed in a Globe and Mail editorial that he is “not an Indian at all.”King wrote that he’d always believed his mother’s story that he was part Cherokee on his estranged father’s side. But recently, he wrote, the Tribal Alliance Against Fraud — an organization that exposes false claims of Native American heritage — informed him that there is no Cherokee ancestry in his family tree, and showed him the genealogical research to prove it. “I’m still reeling,” King, 82, wrote. Sinclair is still reeling, too. In a column for the Winnipeg Free Press, he called the news “a gut punch, pipe bomb, and pulling out the rug from underneath the feet of the publishing world — even if King didn’t do anything out of malice.”Sinclair, an Indigenous studies professor at the University of Manitoba, spoke to As It Happens host Nil Köksal. Here is part of their conversation.Thomas King writes that he is still in shock over all of this. How is it hitting you?There is not one person who has worked in Indigenous studies or Indigenous literature or, frankly, anything involving Canadian literature, that hasn’t heard of Tom King. It’s not only painful. It’s also, I think, a blemish on the entire Canadian literary industry as a whole to not check and to not ask questions and let a person … take up so much space. He also wrote … that he believed what he was told, that his father’s biological father was part-Cherokee. How do you balance the complicated history that many people have while also advocating for accountability and clarity from people who are doing work like Thomas King has been doing?We all have complicated identities, you know. Every Indigenous person has different cultures, races, stories of displacement, identity loss, residential schools.But what we have to do is we often have to [legitimize] ourselves in different contexts and localities, especially when it comes to the work that we do in our own communities.You have to reconnect. You have to be able to answer the questions necessary. And people will trust you because you have said that you’ve done the work. But the fact is that he didn’t do the work. He let others do the work for him.If you don’t even ask for help to be able to reconnect and to find out the answers for the stories that are the most critical, then what happens is you create a mess for everybody else to clean up. And that’s really what’s created now. We all have this situation on our hands where we don’t only have to revisit elements of our career and rewrite and rethink a lot of the things that we’ve been working on, because we built it on trust, we also are now in a situation of mistrusting and harm that’s been created as a result of this process. King, left, is presented the Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction by then-Gov.-Gen David Johnston during a ceremony at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Nov. 26, 2014. (Patrick Doyle/The Canadian Press)How do you process this personally, and then advise others to deal with it? Harm is something that’s real for every Indigenous person. Like, we know how to cope with it, we know to support each other and, most importantly, how to recover and rebuild. Certainly, all of us know how to deal with a situation like this. This really tells you about a question of the Canadian literary landscape and the Canadian culture as a whole. Why is it that so many of these individuals who have very dubious and problematic claims to Indigenous communities have taken up so much space for such a long period of time? And I’m not just thinking of Thomas King.That’s really, I think, the big question.You write in your piece that you met Thomas King through your father, the late Murray Sinclair. And there were rumours swirling [about King’s ancestry]. And Thomas King writes about this as well, that he knew that there were rumours swirling, and they would go away. What did you talk about? What did you say to your father? I’ve heard these rumours going back for over a decade for sure, maybe even longer. And I remember going to my father and talking about it. My father, because of his long relationship with Thomas King, he trusted him. And my father said, you know: I take him at his word. And so I believed my father. And I’m actually very happy that he is not seeing a day like this, because I know he would be profoundly disappointed.I don’t think in any way he would want any of us to create more harm. But I think … he would want us all to turn towards those authors that perhaps we have overlooked in the past, that didn’t win those awards, that didn’t take up the great amount of space [King did], and revisit those authors and give them some attention. University of Manitoba professor Niigaan Sinclair says he’s reeling from the news about King’s identity. (CBC)We’ve covered, of course, in the past, the news about [musician] Buffy Sainte-Marie being exposed, other high-profile Canadians, [author] Joseph Boyden as well. How or where does this case … fit to you? Does it feel different? This one is a little bit different because, in this case, I have a great deal of empathy for if somebody has been told a familial story, someone in their past has told them that they come from a particular community, they may want to believe that. They have such a desire to believe that they don’t do the research necessary, even when others clearly can do the research and can find the answers. And that if they don’t pursue that, I can have some empathy for that. But where the empathy stops is when you take up so much space, and you win all of these awards, and you then displace real-life Indigenous writers over that long period of time. If someone wants to talk about Indigenous identity for 25 books and impact not just ourselves, but an entire country, then what does that say about the country itself and the country that we are living in? I think many of us want to have a great deal of optimism and believe that reconciliation is moving and changing and making us more progressive than ever before. But this really hearkens to a time in this country in which non-Indigenous peoples are dictating the lives, the parameters, the arts of Indigenous Peoples. And we need to move on from that.Interview with Niigaan Sinclair produced by Sarah Jackson

Monday, 12 Jan 2026

Canada – The Illusion

Search

Have an existing account?

Sign In

© 2022 Foxiz News Network. Ruby Design Company. All Rights Reserved.

You May also Like

- More News:

- history

- Standing Bear Network

- John Gonzalez

- ᐊᔭᐦᑊ ayahp — It happened

- Creation

- Beneath the Water

- Olympic gold medal

- Jim Thorpe

- type O blood

- the bringer of life

- Raven

- Wás’agi

- NoiseCat

- 'Sugarcane'

- The rivers still sing

- ᑲᓂᐸᐏᐟ ᒪᐢᑿ

- ᐅᑳᐤ okâw — We remember

- ᐊᓂᓈᐯᐃᐧᐣ aninâpêwin — Truth

- This is what it means to be human.

- Nokoma