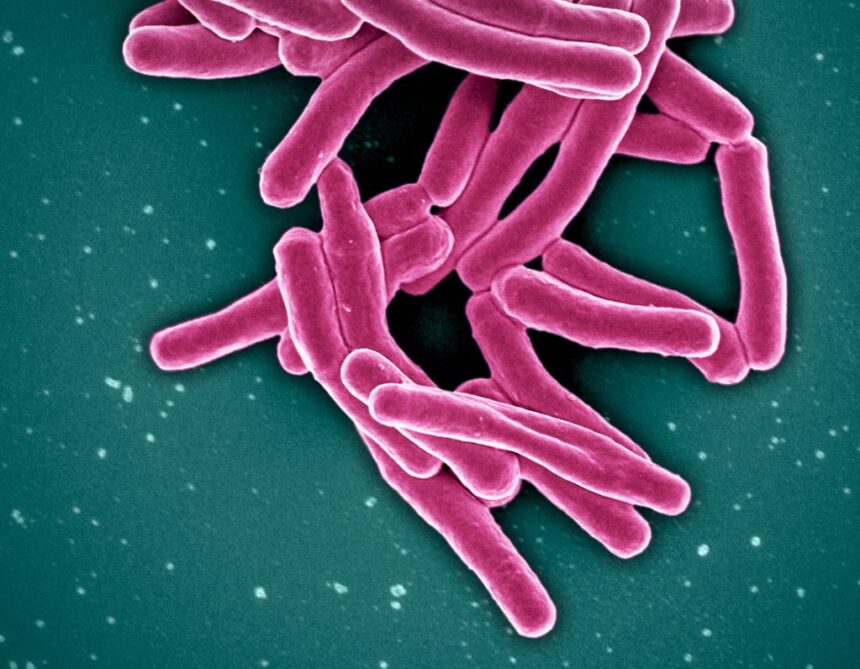

Tuberculosis cases are expected to reach record numbers in Nunavik, the Inuit region comprising 14 communities in the far north of Quebec, according to the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services [NRBHSS]. In June, mayors of all 14 communities wrote a joint letter requesting help from Quebec’s Minister of Health and Social Services in tackling numbers that suggested 2025 would be the worst ever year for TB in Nunavik. “We heard last year there were 94 [cases], and in April [of 2025] there were about 30, 40. It’s still growing in Nunavik,” Qialluk Nappaaluk, mayor of Kangiqsujuaq told APTN News. “So the mayors [wrote] a letter asking for more funding from government, because we need tools, X-ray [machines].” According to the NRBHSS, the 94 cases in 2024 represented the “highest TB rates in recent history.” “The incidence of TB in Nunavik is 1,000 times higher than among non-Indigenous, Canadian-born individuals and in some communities, it is 10,000 times higher,” the NRBHSS reported in March. By July 30, 2025, the region had seen 70 cases, suggesting a strong likelihood that 2025 will be Nunavik’s worst year for TB. “So many communities have been free of TB for decades,” said Dr. Faiz Ahmad Khan, director of the tuberculosis clinic at McGill University Health Centre’s Montreal Chest Institute. “We talk about TB rising in Nunavik, but it’s also not rising in all communities. It’s about seven or eight of the 14 at this point. Really it’s been over the last 10 years that in some communities that had been free of TB for decades, it’s reappeared. It can spread quite rapidly and extensively.” Ahmad Khan is the only pulmonary doctor who travels to Nunavik to see patients and who is also a researcher on improving TB care in Nunavik. “What we’ve seen, and this situation is worsening, is that the medical tools and the personnel needed to intervene to slow down the spread of tuberculosis have been insufficient for many years.” Why this, and why now? Ahmad Khan stressed TB is a complicated illness to identify and equally complicated to treat. It can be both active and “sleeping.” In TB’s active state, the bacteria is growing in and damaging the sick person’s body, usually their lungs, while making the person contagious. In the case of “sleeping tuberculosis,” the bacteria is not causing damage to the body, growing rapidly, or spreading to other people. “That’s why it’s so important, when there is TB in a community, to find people who have active disease as soon as possible,” Ahmad Khan stressed, “and shortly thereafter, find people that may have contracted the infection so that you can prevent them from getting to active TB.” Yet the transmission process is long and just as complicated, noted Dr. Yassen Tcholakov, clinical lead on infectious diseases for the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services. “Most people fall ill from TB within the first two to three years after being exposed,” Tcholakov explained to APTN. “It’s not something that you get an exposure and then the next week you’re sick. Usually it takes a long period of time. Children usually get sick much faster. “But for a healthy adult, usually it lasts two to three years, and it can last longer, sometimes up to ten years.” Tcholakov said the circumstances in Nunavik are ideal for the disease to spread. Many Nunavimmiut live in crowded households near one another. Meanwhile, though TB is one of the world’s oldest diseases, Tcholakov stressed that the available tools for diagnosing the disease are still imperfect, even in the 21st century, making it harder to get clear diagnostics for tuberculosis. Read more: ‘Unmanageable’: Nunavut hamlet sets up satellite centre for TB treatment In Pangnirtung the housing shortage is allowing an old disease and new virus to thrive Once the disease has been diagnosed, a second challenge is the length of the treatment. On average, TB takes six months of daily treatments featuring multiple medications. Treatment can run to nine months for some patients. “At the start of the treatment, it’s four medications,” Tcholakov said. “We eventually go down after a few weeks of treatment in most cases, but it still means that people have to take pills very, very often.” This treatment would be demanding in southern hospitals prepared for complex cases, but all parties said Nunavik is struggling to do its best with far less medical infrastructure. Nunavik’s communities “are very remote and sometimes have certain very small amounts of health services available,” Tcholakov said. “Sometimes not all of the health services that would be needed to treat TB are available in the community. “It creates both delays in getting treatment, but also makes treatment much more complex, meaning that people have to then travel outside of the community to get regular care.” Tcholakov stressed that the combination of these factors benefits an infectious disease that spreads from person to person by providing more time for it to spread before people are diagnosed. That’s to say nothing of the stigma of TB, whose shadow haunts Nunavimmiut. Decades ago, people were sent to tuberculosis hospitals in the south. “Our great-grandparents or grandparents, they didn’t come back,” Nappaaluk said. “They died from the TB.” One of the things that makes tuberculosis so frightening, she said, is its potential for permanent damage that can be so serious it shortens lifespans. “TB can eat our lungs when they’re affected,” she said. “It’s not going to heal the way it was. So before destroying our lungs or [letting it] make any holes, we have to try to stop it.” Nappaaluk added she was afraid of TB before she learned it was treatable—under the right conditions. “My mother, she was sent down when she had the TB in the 1950s and 1960s and today it’s more easy,” she said. “We don’t have to leave from our home like the way they used to. “It’s much more easy if we just have to take the pills. I’m sure it’s going to be better if they have more tools.” For the moment, Ahmad Khan said, it is not getting better. “TB is increasing rapidly and the pace at which it’s increasing, it’s outpacing how quickly resources have been added and made available to address these kinds of TB rates.” How to beat TB Along with the Nunavik communities not seeing TB resurgences, Tcholakov points to the example of Nunatsiavut, the region of Labrador home to Inuit. “Nunatsiavut deployed TB interventions similar to the ones that we’re aiming to deploy, but sometimes struggling in Nunavik,” Tcholakov said. “And over time, they reduced their rates of TB to basically not having any cases over the last few years. “They’re now a few years out of their last actual case of TB disease. So it is possible to treat TB, even in settings like the small health centers in small communities in Nunavik.” The components of treatment for TB are not complex, he said. Chest X-rays and spit samples help with diagnosing the illness, while under-the-skin injections and antibiotics form the backbone of treatment. “But some of those tools are not available or not readily available in communities,” Tcholakov said. “When we’re talking about X-rays, some communities that have had outbreaks have not benefited from having an X-ray on the ground. “There are some recent changes because we’ve recently deployed mobile X-ray machines.” Being able to move X-ray machines into the communities reverses the tradition of flying sick people out in order to be tested in other places. Nappaaluk, Tcholakov, and Ahmad Khan all stress the NRBHSS and local health centres are doing everything they can with the resources they have available. Unfortunately, those resources are simply not enough. For Nappaaluk, there’s no shortage of needs. “We need doctors,” she said. “We need more employees because when it’s active, it could spread. We need special people who know how to take care of the TB. It’s not the same with broken bones.” She underlined that it would be ideal for Inuit to become these trained professionals. “We have to train the Inuit because they’re going to be home,” Nappaaluk said. “If they’re wanting to learn, they can teach how to take care of the TB, but we need funding to keep for the training. If we can find Inuit to become TB nurses, I think it’s getting more easier because they speak in Inuktitut. “They can explain the TB, what it was, and they’re going to be there in their own home. I hope we’re all going to see that.” Tcholakov agreed, noting “in all communities in Nunavik, we need to be able to provide primary care for TB in the community itself. The patient shouldn’t be moving to get basic services that take five minutes.” The challenge of Nunavik Yet multiple factors complicate even simple needs. For one, Tcholakov noted, understaffed health centres in Nunavik need to prioritize emergencies, meaning they’re often forced to push work on TB to the backburner as they tackle events like ATV crashes. But even when the health centres have the time to focus on TB, they often don’t have the physical space. The housing crisis in the north leads to overcrowding that favours the spread of TB, but it also means there’s nowhere to stay for the extra medical professionals the communities need so badly. None of these aspects is optional, said Ahmad Khan. Because anyone can be infected with TB for months before they feel sick, the primary intervention to slow it down involves screening all members of whole communities. “It needs to happen regularly. And then attached to that is then also screening for the people with sleeping TB because if you don’t find them, well, they’re the ones who are going to also progress to the active TB.” Yet Ahmad Khan said both regional and provincial governments need to understand they must fund more than the basics of treatment. “We also have to make sure that we support the people and families affected by TB. It is a long treatment. It can involve isolation. There’s a lot of stigma.” TB is the only disease for which the health care system can legally force a person to take treatment. “That should also come with some obligation to ensure people have adequate support to get them through that treatment,” Ahmad Khan said. That part, he said, is multifaceted: it may involve ensuring patients continue receiving food, financial support, and child care throughout their treatment, or may include other concerns raised by the specific circumstance of a minimum six-month treatment schedule. “It’s not an easy treatment to undertake,” Ahmad Khan said, “and people who are doing it are doing it for two reasons. It’s for their own health but also to protect their community, because once you start treatment for active TB, it’s very soon after it’s no longer contagious.” Screening is a pivotal practice for TB reduction but it is not the only factor. “Screening can’t just be implemented in the absence of the resources to provide the adequate treatment and support to the patients who are then discovered to have TB,” Ahmad Khan said. “Both those things are needed urgently. We can’t say screening without increasing the resources for treatment and support, and we can’t just say, ‘Just increase the resources for treatment and support’ because, you know, it’ll continue spreading without screening.” The secret is resources As a physician treating both patients in Nunavik and those sick enough to be flown to Montreal for treatment and also a researcher on TB, Ahmad Khan is convinced a real plan for ending TB in the region needs to begin with increased funding. “The first thing that the provincial government could do is unleash the resources, the additional budget that hospitals and clinics need to ensure rapid and effective care for people with TB, or with sleeping TB, because you have to address both,” he said. “This situation is worsening, and the medical tools and the personnel needed to intervene to slow down the spread of tuberculosis have been insufficient for many years.” That funding could help address a variety of the needs that have gone unmet for too long, whether in staffing, in equipment (like X-ray machines), or in housing. Nappaaluk is focused on planning for what comes next. She said she’s heard Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services has committed to help the community, but she doesn’t know when that will begin. Next week, Nunavik mayors plan to meet again to discuss what might happen next with the province. “We will get more information,” Nappaaluk said. “I really could not say how they’re going to help, but we still need those tools for decreasing the TB.” APTN contacted Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services for comment on how they plan to address the increasing TB caseload in Nunavik, but we did not hear back prior to this article’s publication. Continue Reading

Tuberculosis spike in Nunavik has complex causes, needs complex solutions: experts

Leave a Comment