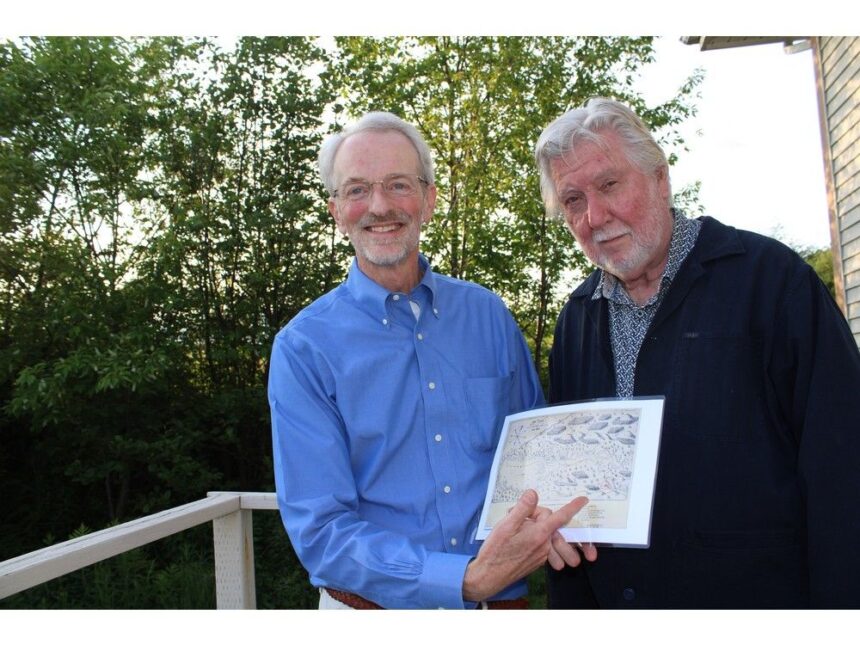

Published Jun 16, 2025 • 5 minute readAuthor Mark Borton, left, and professional heritage consultant Brian Arnott are working on a collaborative project seeking to find historically significant sites along the Allains River in Annapolis County. Photo by Jason Malloy /Annapolis Valley RegisterThere’s a lot of information to comb through when looking for remnants of a 400-year-old grist mill.Some of it is helpful. Some of it is not.Mark Borton, an author from Connecticut, knows all too well. He’s been researching the first grist mill in North America, north of Spanish Mexico, for 2.5 years. Jean de Poutrincourt built the water-powered mill at Port Royal in 1607. It was burned in 1643 and rebuilt.THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY.Subscribe now to access this story and more:Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsSUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES.Subscribe or sign in to your account to continue your reading experience.Unlimited access to the website and appExclusive access to premium content, newsletters and podcastsFull access to the e-Edition app, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment onEnjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalistsSupport local journalists and the next generation of journalistsRegister to unlock more articles.Create an account or sign in to continue your reading experience.Access additional stories every monthShare your thoughts and join the conversation in our commenting communityGet email updates from your favourite authorsSign In or Create an AccountorArticle content“This is a story about clues … and also about red herrings,” he told a crowd of about 75 people June 13 at the Lower Granville Community Hall during his first public presentation about his research. “Untangling this is fun and frustrating.”Read More Author to present research of collaborative effort to find Poutrincourt’s 1607 mill Friendship between Mi’kmaq, French recognized during ceremony in Lower Granville, N.S. New events planned to celebrate Dugua de Mons at Port Royal, N.S. A group of experts, scholars, interested area residents and private property owners are working with him on the collaborative project.“When Mark and I had our first conversation, I was very intrigued,” said professional heritage consultant Brian Arnott. “He sent me the material and I thought this is fabulous work. …“This is some of the best I’ve ever seen. The work is being done very, very thoroughly.”Article contentThe work is much deeper than one mill. Borton said there were a couple other mills dating back to the 1600s in the area that hold significant historical value as well as an Indigenous fishing weir. He also wants to find and catalogue the millstones.“Your little river has a lot of big claims,” Borton said.“Your mills are really important.”IndustrializationThe technology dates back over 2000 years in Europe and Asia. A mill could do about 100 times the work a person could by hand. Using a quern, a hand-cranked mill, it would take someone four hours to grind enough grain to make one loaf of bread.“They brought the innovative technology with them because they were here to stay. They were colonizing,” Borton said of the French explorers. “For better or worse, the industrialization of North America starts on the Lequille River.”Arnott attended the public session and visited one of the sites with Borton the next day.Article content“If it can be found, it’s monumental in terms of its significance,” he said of the original mill. “It’s a pivotal moment in the history of the North American continent,” north of Mexico.And while those original mills are no longer visible, Borton thinks remnants still exist.“I believe that there is evidence still in the marsh of all of that history,” he said. “That mud is a fabulous preservative.”Fact from fictionBorton has come across a series of maps. They include one by the French expedition’s corporate lawyer Marc Lescarbot and another by the expedition’s cartographer Samuel de Champlain.While Borton said Lescarbot’s work is beautiful and well-illustrated, 21 of the 23 buildings on it are fake and one, the Habitation, is exaggerated. The river is big, wide and mostly straight.“This is a highly detailed map, but it’s not accurate,” he said.Article content Marc Lescarbot’s 1609 map shows the mill on the northeast bank of the Allains River. Photo by ContributedBorton noted Champlain’s map included a compass, scale, water depths and a detail key explaining the symbols.“There’s nothing fake here. Everything here is legit.”Lescarbot showed a three-storey mill on the northeast side of the Allains River, which is also known as Lequille River amongst other names through the years. Champlain has a one-storey mill on the southwest side of the river, a quarter of a mile from where Lescarbot marked it.He’s studied Jean-Baptiste Franquelin’s map. It shows a 1.5-storey mill on the northeast side of the river. Borton pointed out it would be the rebuilt mill after the original one burned. Franquelin created a second map the same year and it showed a two-storey mill on the southwest side of the river.“Same guy, same year, same mill, two different sides of the river (and) two different size of buildings,” Borton said.Article contentHe’s come across another map from the early 1700s. It said the old Scotch Fort was built in Granville, but it wasn’t. The error continued through a half a dozen future maps.“You can see how things start to snowball,” Borton said.Moving forwardBorton has received a Nova Scotia archeological reconnaissance permit to begin a no-touch investigation. His first 400-page report permitted him to continue the project.He has a hypothesis based on his experience and 2.5 years researching the original mill in the first European settlement north of Florida. Mark Borton at Fort Anne National Historic Site in Annapolis Royal with ancient millstone. Photo by ContributedBorton said there’s probably 10 different locations historians have said the original mill could be. The author said there were two people who saw and mapped it, Lescarbot and Champlain.“One of them was wrong and everybody else (has) just a theory, including me,” he said.“I think we should go back to Champlain’s map because it’s probably the most accurate in terms of location and probably the most accurate in terms of what the building looked like.”Article contentHe would like to see more lidar work done in the area as well subsurface remote sensing, including ground-penetrating radar, metal detecting and magnetometers, to map what’s underground.“I think I can explain things, but I can’t prove things,” he said.“And really, the point is to find it – not prove me right or wrong.”Borton said he sees a professional from Canada leading the archeological investigation.Arnott cautioned they are still in the very early days with hopes of going forward in a systematic, professional manner.“I hope you will join us in the search for answers,” Borton told the crowd at the end of the night.Upcoming eventsJune 13-1810 a.m. to 4 p.m. – An art exhibit reflecting the Mi’kmaq, the French, the Habitation and tidal mills. At the Lower Granville Hall, 3551 Granville Rd., Port Royal. About 20 local artists will also be creating art at Port Royal National Historic Site during exhibit.Monday, June 166 p.m. – Poutrincourt’s Mill Monument. An outdoor presentation hosted by the County of Annapolis on the possible site of the historic 1607 tidal mill in Lequille.Tuesday, June 176 p.m. – The lives and legacies of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, and Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt. Slideshow presentation by Christine Igot at the Lower Granville Hall.Article content

U.S. author presents research on location of Poutrincourts 1607 mill